Welcome to Londonist: Time Machine in which, today, I live up to the newsletter’s name by describing a virtual time machine. This is going out on a tumultuous US election results day, so I imagine it’ll attract very few readers. Then again, perhaps a time machine is just what we need right now. Enjoy.

A “Street View” for History

Imagine you could travel back in time via Google Street View. Imagine you could see London how it used to be — not from maps or one-off images, but in a navigable streetscape through which you might virtually walk.

You can do this already, of course. A bit. Google’s navigation includes an option to turn the dial back to the far-off days of 2008 — when the company first brought its cameras to the London streets. But I want to go further. I want to be able to see what a street looked like in the year of my birth, or wander along a Blitz-damaged Bishopsgate in 1945. While I’m dreaming, why not go further still? Who wouldn’t want to take stroll along the Fleet Street of Dr Johnson, or the newly minted Regent Street of the 1819?

It could be done. London has been documented by illustrators and photographers for centuries. Every building, certainly in the central area, must have been recorded from multiple angles multiple times. Why can’t someone (and it’d have to be a big someone like Google themselves) pull it all together into an explorable, immersive city: a Street View for history?

Such a project would pose significant challenges, but what a mouthwatering prospect it is. In today’s article, I want to think through what an historical Street View might look like and what hurdles it faces. Why, to date, has nobody built an accurate historical model of London that spans the centuries?

Cards on the table: I’m writing this from a position of technical ignorance but infinite enthusiasm. I’m thinking out loud, with perhaps a naive appreciation of what’s possible or, perhaps, lack of appreciation for what is already in the works. I would very much welcome comments below from anyone with more expertise in this area.

First, though, an historical interlude.

An early Victorian Street View

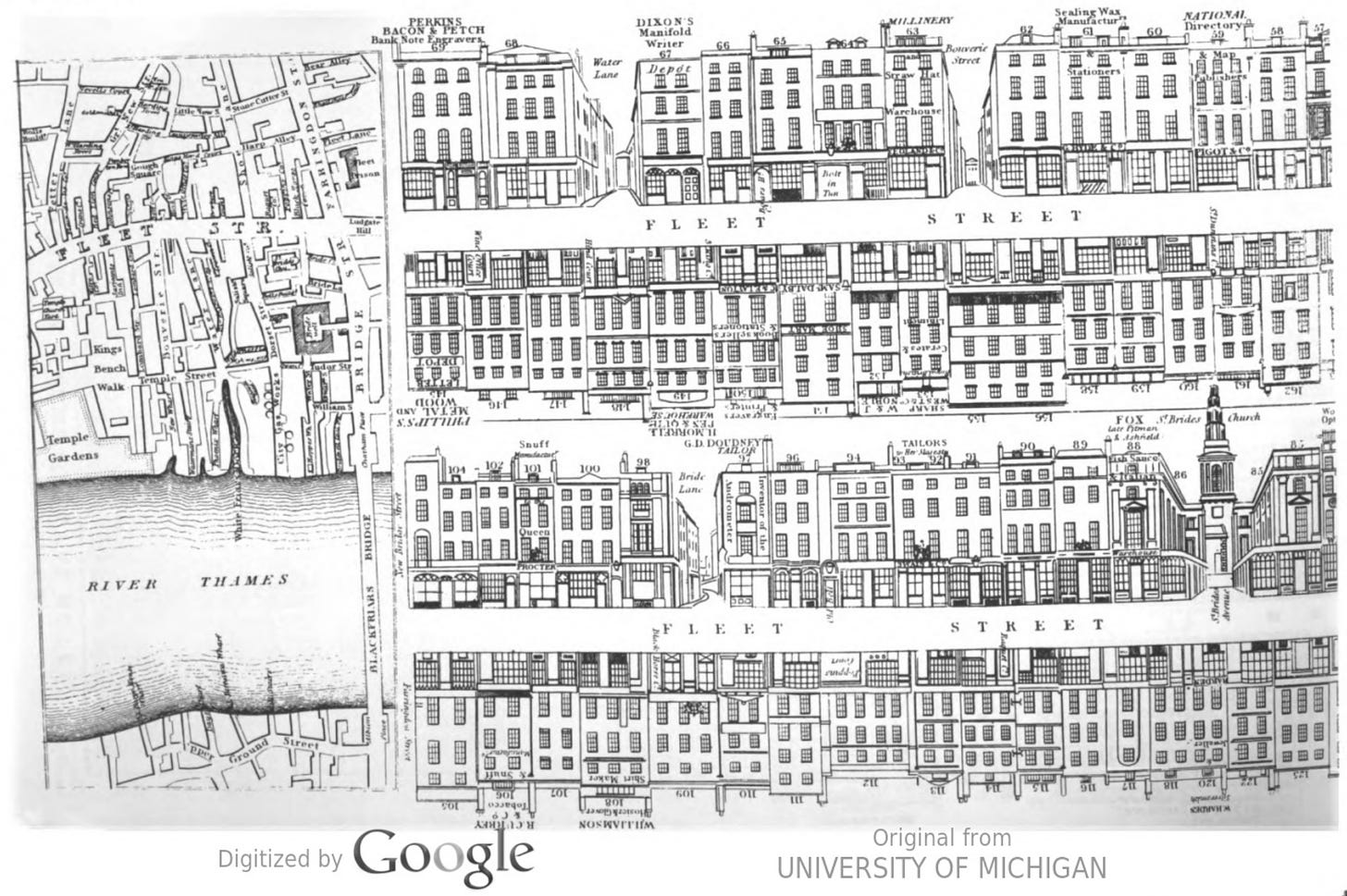

London had its own form of Street View 170 years before Google came along. It even used the same name. John Tallis’s Street Views of London was published in instalments between 1838 and 1840. Its aim was to reproduce the appearance of every building along both sides of the street in all important thoroughfares — 74 in all, and ranging across the West End and Square Mile. Each edition contained historical commentary and a street directory. Here’s a typical page, so you can get a feel for the scope of the project:

As you can see, the Street Views are rudimentary. They are basic pen outlines of elevations, as might be found on architects’ plans. Nevertheless, they are the most comprehensive representation we have of the early Victorian city from street level.

Tallis was able to sell copies of the street views in “all Booksellers and Toyshops” for three-half-pence, a remarkably low cost for such a work-intensive project. This was achieved by the most cunning of wheezes. Tallis’s draughtsman would draw every shop elevation on a particular street, but would only sketch in the names of those who paid a contribution. The project paid for itself via a disguised form of advertising (alongside more traditional advertising). In a circular bit of salesmanship, these friendly businesses may then have helped to sell copies of the finished product to their customers. The Tallis street views were works of both intellectual and commercial creativity.

Funnily enough, we don’t know exactly which John Tallis was behind these innovations. The Tallis firm in Warwick Square behind the Old Bailey was managed by father and son of the same name. Historians usually credit Tallis Jr (1817-1876) as the man with the inspiration. Either way, I think we can be fairly confident that it wasn’t John yee haw Tallis, as the rather slim Wikipedia page currently has it.

Original copies of Tallis’s street views are now rare; complete sets, vanishingly so. Guildhall Library, the British Library and the London Archives have most of them. The best way to see the full collection on the page is to get hold of a bound reprint, published by the London Topographical Society in 2002.

How to build a time machine

With the Tallis views we have reasonably accurate sketches of every building on 74 major London streets from around 1840. The plans were revised and republished a decade later, giving us another set. These provide a voluminous if somewhat austere starting point on which to build our historical street view. Here’s how such a project could pan out.

The first job is to get all of the Tallis views into our hypothetical History Street View, lined up with the modern elevations, and indexed to 1840. They’d need a tidy up, and perhaps a splash of colour, but it could be done. That would be the seed around which all else could grow.

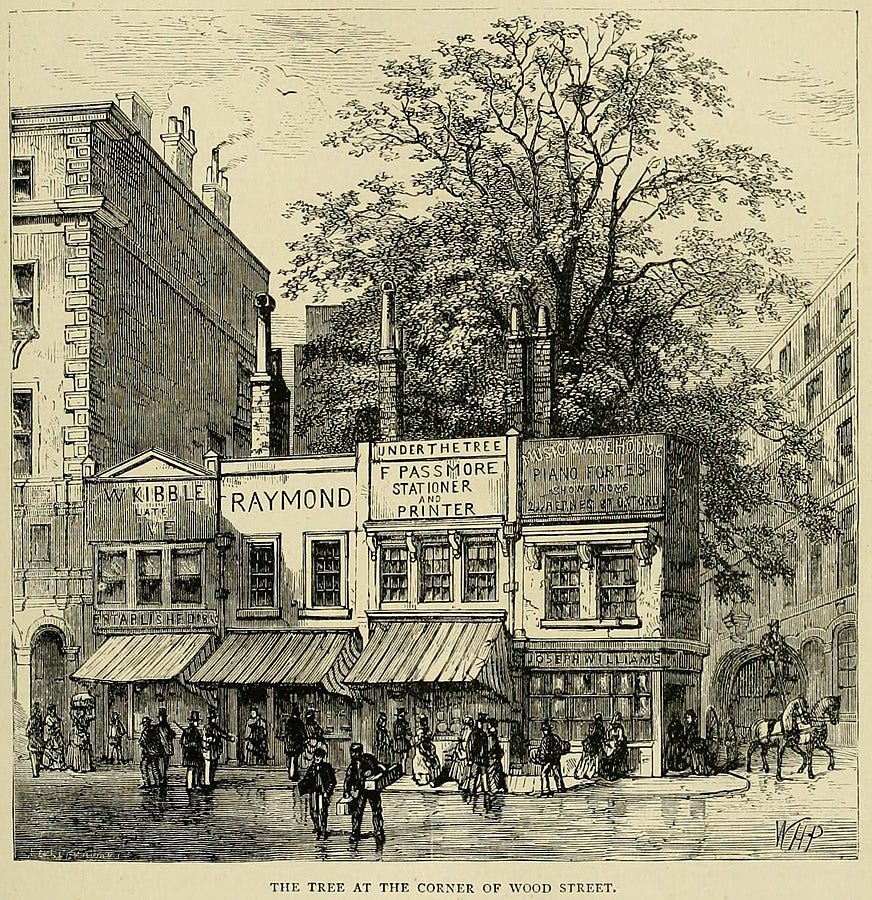

Next we search the pictorial universe for the low-hanging fruit. We’re looking for images of London without copyright restrictions, which show buildings head-on, and preferably with little clutter. Photos like this, or drawings like that. We then add these into the database, with both time and location coordinates.

Having exhausted that subset, we can now work on the tougher nuts. Public domain images that are faint or drawn at oblique angles could perhaps be rescued with a bit of AI manipulation. We could also find many thousands of further images, not freely available online, by scanning old books that are long out of copyright. Finally, with a budget, we could license additional historic images from photographic archives and other proprietary sources. The aim is to bring every usable historic image of London together in one navigable space. Wouldn’t it be marvellous?

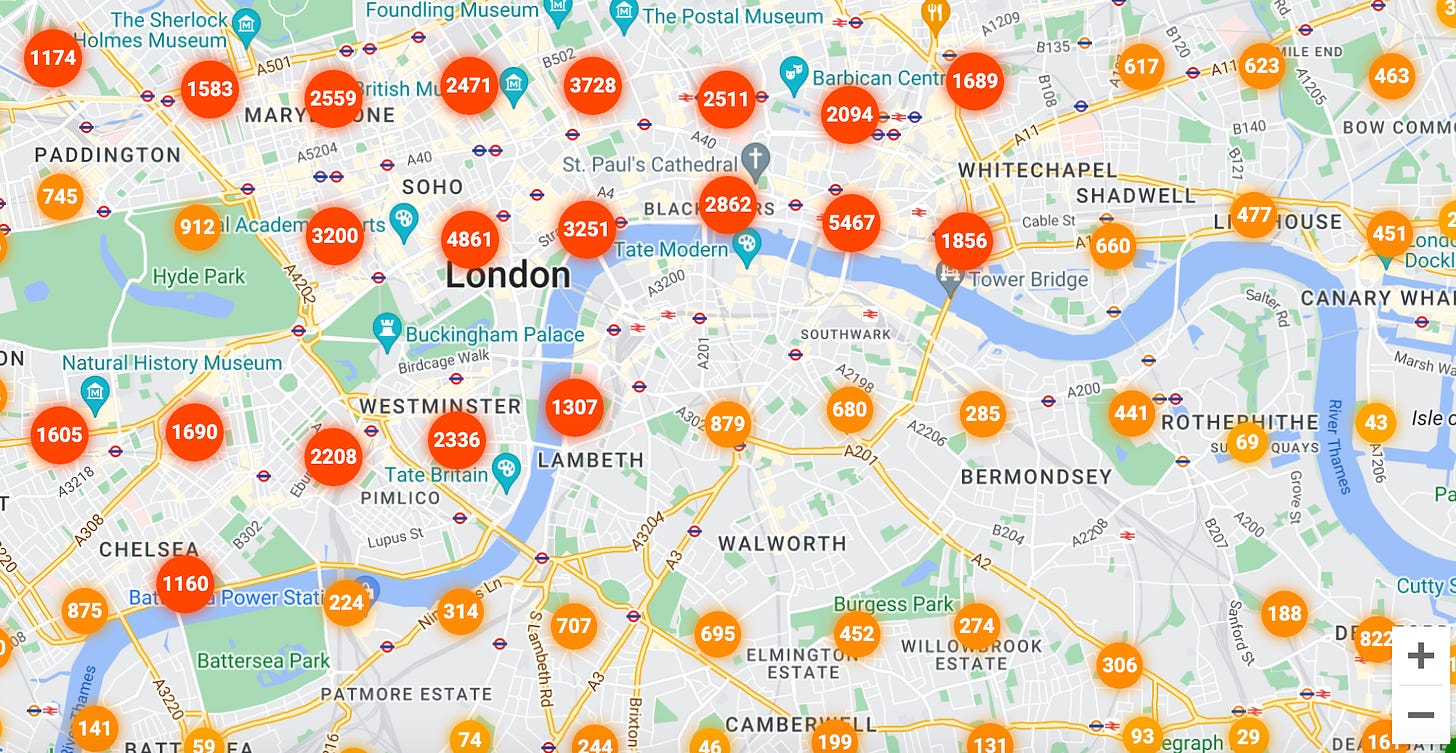

To be clear, I’m not talking about an interface with clickable pins on a map. That’s already been done many times, most brilliantly by the London Picture Archive. Their resource contains tens of thousands of historic photos, all geolocated onto a zoomable map. It’s brilliant; have a go.

I want to see the idea taken to the next level, where all these photos and more are stitched together into a Street View-like environment; a streetscape you could effectively “walk through”, and all of it future-proofed for more immersive technologies that might one day allow a “holodeck”-like experience.

So what’s stopping this?

Well, quite a lot, actually. You can probably think of your own objections. Acquiring all the images and copyrights would be a formidable task to start with. But the trickiest part would be stitching everything together. Our source material would be taken from wildly different angles and elevations. Some images would be black and white, others colour; some photographic, some painted, some sketched. Bringing all this into a coherent whole would be messy, to say the least.

There is a way around this. Don’t stick the raw photos or drawings into History Street View. Instead, use AI tools to scan each image, identify the individual buildings, convert to 3-D wireframes, and then render a realistic colour facade over the top. You wouldn’t need to know the full depth of the building for a Street View-style implementation, you just need an approximation of the front parts to make this work.

A digital model has any number of advantages over a flat image. Buildings and streets could be viewed at any angle or zoom. The assemblage of wireframes would look much more cohesive than a patchwork of different artistic styles. And no historical content need be lost. The original image, on which the 3-D wireframe was based, could be accessed with a click/tap on the front door.

Other challenges exist. One concerns the interface. The current Street View lets us go back to 2012 or 2019 without too much bother, because Google has imagery for pretty much every corner of London from those and other recent years. It took the photos itself. If we dial back to, say, 1871, however, we’re going to have a very gappy dataset. We will find many drawings and photos from this one year but not enough to fill out an entire street, let alone the entire city. We may have to take a decadal approach, or fill in the gaps with buildings pulled from slightly earlier views, on the basis that most would still be there. Indeed, lots of old images are of uncertain date (we’ve all seen captions like “image circa 1860”), so a certain amount of fuzziness would be baked into the system.

Perhaps the greatest challenge, as with anything, is the funding. Who would pay for this, and why? Is it marketable? Crucial questions… but as this is only a thought experiment in a history newsletter, and not a business proposal, I feel no need to try and answer them1.

How would it be used?

Oh, in so many ways… First, of course, it’d simply be heaps of fun to wander through the streets of an accurately rendered Victorian London. Who wouldn’t want to play with that? Imagine retracing familiar steps, such as the route from a tube station to your office, but experiencing the streets as they appeared 150 years ago, right down to the advertisements. Alternatively, you could stand on one spot and see how a single building plot has changed through the decades or centuries. All this could be done with a VR headset rather than a traditional screen, making it feel proper immersive.

History Street View would also be a valuable educational tool, especially if the historical streetscapes were overlaid with annotations. Perhaps you could “open” the door of a building to read about its history or watch a video. The model would also help archaeologists, historians, novelists, film-makers and video-game designers to better appreciate the back-story of a particular area of London. It could also assist in recreating long-lost eras. We have no contemporary images of Roman London, but the period could be partly reconstructed and visualised by feeding all archaeological data into the same interface and extrapolating.

No need to limit things to the streets, either. Views from the river have been well recorded over the centuries. In 1829, for example, both banks of the Thames were sketched in detail between Richmond and Westminster by Samuel Leigh. I could also imagine the model going down into tube stations and other subterranean spaces, to show how they have changed with time.

The data set would only grow and improve as fresh archival material comes to light, and it could be merged with 3-D models of modern London, which already exist (including in the Google Earth interface). We would then have a virtual London complete in both time and space. The whole magnificence of London in one four-dimensional bubble.

All this could be done for other cities, too. I’m only banging on about London because, well, that’s what I do. Any city with a rich illustrated history could join in, just as with regular Street View.

Maybe all this is really obvious, and tech whizzes or game designers are already putting such things together. Maybe it’d be too complex or too expensive to merit attention. But until we invent a real time machine, I can’t think of any better way of visualising the past than an historically accurate Street View.

Thanks for reading! As I said at the top, this is written largely from a position of ignorance, so I’m very happy for people with more knowledge to chip in and point out all the flaws. Leave a comment below, or feel free to email me any time on matt@londonist.com

That said, I wonder if we could take a leaf from Mr Tallis’s book and ask whichever business is on each site today to sponsor their patch of History Street View? We wouldn’t want sponsor messaging all over the place, but perhaps they could be hidden as easter eggs behind the doors and windows of the wireframes…

Street View for History is a brilliant idea that deserves support from London Museum, London Archives and the Corporation's Destination City programme.

Closure of the Museum two years ago prompted me to muse on how to create a Museum of the Streets, and I discovered that back in 2010 the Museum launched an app called Streetmuseum that matched views of today and yesterday. Unfortunately operating system changes mean it isn't now available. However, there are other developments that chime well with a historical Street View, which I've noted in updates to the original MotS idea https://connections.commons.london/museum-of-the-streets/

Here's more on the StreetMuseum app

https://diallingthepast.wordpress.com/2016/08/24/heritage-everyware-streetmuseum-augmented-reality-app-for-citywide-sightseeing/

I'm 100% with you. Fascinating! I didn't realise that the street facades had been documented to such an extent. One of my favourite games is to superimpose Victorian maps onto the modern equivalent (via the Nat Library of Scotland online), which gives you an idea of old road patterns and topography- but 3D street view is the obvious next step.