Welcome to Londonist: Time Machine, a newsletter for anyone interested in the history of London.

Marble Arch once fronted Buckingham Palace.

London Bridge now stands in Arizona.

The Crystal Palace fled south from Hyde Park to Sydenham.

Just three of the best-known examples of “London buildings that can’t keep still”. There are many more.

It’s something of a disorder in this city. A church might walk out of its own parish, to secrete (and consecrate) itself in a whole different borough. Industrial relics steam ahead to a new location. Arches march, tombs trek and halls hike. At least two London buildings have moved on more than one occasion.

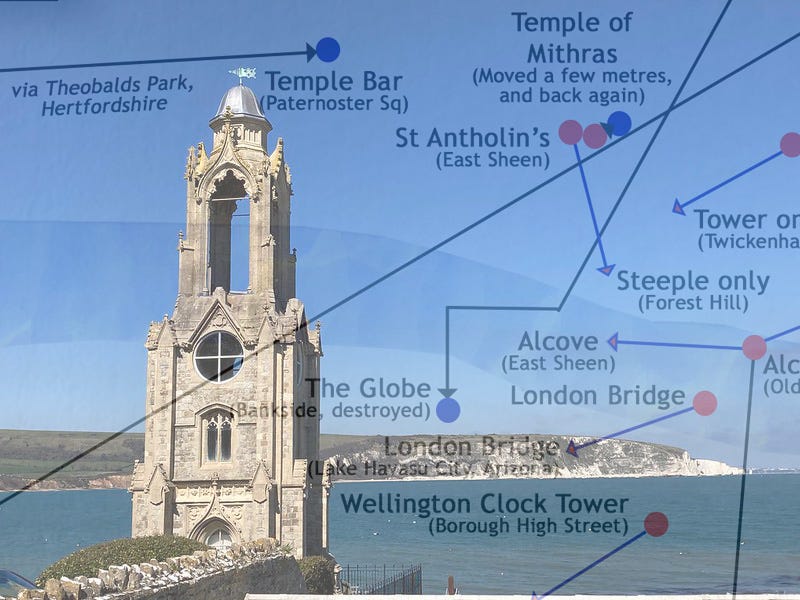

It’s time to pin down this peregrinating architecture. In today’s Londonist: Time Machine, I’ve started a list of buildings that are no longer in their original place of residence. And, being me, I’ve also made you a map.

Note on inclusions: This is the longest newsletter in Londonist: Time Machine’s history. It could have been much longer, such is the number of itinerant structures in the capital. As a rule of thumb, I’ve only included full buildings or structures you could step inside… with exceptions for the landmarks of “Eros” and Seven Dials. I’ve left out numerous smaller structures, statues and memorials, such as the obelisk in Salisbury Square, this drinking fountain near St Paul’s, this hilarious statue of Charles II stamping on Oliver Cromwell, and things like Cleopatra’s Needle, which moved into London. Or stuff like the old Wembley Stadium, which still exists as a pile of rubble under Northala Fields. So much movement. Nomadic city.

Please do feel free to highlight other examples in the comments, even small ones. Now, let’s get stuck in — in alphabetical order.

Alcoves of Old London Bridge: The medieval bridge was demolished around 200 years ago. It lives on; a stone here, a coat-of-arms there. Perhaps the best known leftovers are the four stone alcoves. (These are not medieval. They were added to the bridge in 1760 after the old housing had been cleared away.) One has evacuated only as far as Guy’s Hospital, where it has ingested a sculpture of John Keats. Two have fled to the eastern end of Victoria Park. A fourth, and lesser known survivor, can be found within the grounds of the Courtlands Estate in East Sheen. These are the largest surviving fragments, but I’ve collected together information on other bits of bridge in this article.

All Hallows, Lombard Street: The first of several itinerant churches in this list. All Hallows, in its earliest form, predated the Norman conquest. It was rebuilt by Wren after the Great Fire and lasted into the 20th century. The church did not quite live long enough to brave the Blitz. Instead, it was dismantled in 1937, after it was found to be in bad repair. The plain tower would rise again, however, over in the west London suburb of Twickenham. It was reconsecrated in November 1940 — perhaps the only church to be raised instead of razed during the Blitz.

Crosby Hall: The City of London’s only surviving medieval house can be found in Chelsea. Crosby Hall was built on Bishopsgate in the 1460s, a century before Shakespeare drew his first breath. Richard III occasionally lodged within. And to tie those two sentences together, the hall is name-checked in the play of Richard III. It went on to shelter Catherine of Aragon, Thomas More and Walter Raleigh (at different times, alas… now there’s a Tudor alt.history novel waiting to be written). This preposterously historical building survived the great fire, but was often threatened with demolition. In 1910, it was moved five miles to Chelsea, close to the site of Thomas More’s main home. It’s been well maintained and even expanded since, and now goes by the name of Crosby-Moran Hall, after the private owner who now resides therein. Of all the buildings in London I’ve never set foot inside, this is top of my wish-list (well, after the secret tunnels below Whitehall). So, I’m not ashamed to beg… if anyone knows Dr Christopher Moran and can convince him that I’m a genuinely fascinated London geek who would be overjoyed to take a look around his home… then please put me in touch!

Crystal Palace: London’s most famous “building that moved”. It was built in Hyde Park to house the 1851 Great Exhibition, arguably the greatest cultural event in our city’s history, whose content and legacy I’ve described previously. Once the party was over, this astoundingly large glass house was dismantled and re-erected on the slopes of Sydenham. It flourished for another 80 years, mostly as an events and exhibitions centre, before burning down in 1936. Such was the building’s impact that the entire area is now named after it, along with a railway station, football team and one of London’s most splendid parks.

“Eros”: I put our winged friend in quote marks because I know lots of people like to insist that he’s Anteros (even though the evidence for this is scant). Whoever the youthful archer is, he makes good use of those wings. This is one of London’s most flighty statues. He stayed put from his unveiling in 1892 until 1925, when he was shifted to Embankment Gardens while more earthly beings constructed Piccadilly Circus tube station. He returned in 1931, only to be turfed out again in 1939 to avoid the Blitz. Eros’s war was spent in storage in Egham, Surrey. He only returned to his spiritual home in 1947. Yet another removal occurred in the mid-80s for restoration, and he now stands in a slightly different part of the Circus to where he started.

Globe, The: Everyone knows Shakespeare’s Globe. The modern one is a 1990s reconstruction and, splendid though it may be, it’s on the wrong site. The original, which burned down in 1613, was a few hundred metres south-east on Park Street. Go have a look — there’s a neat little display there. Even this was not its first site. The timbers came from an earlier theatre, known thrillingly as ‘The Theatre’, up in Shoreditch. Owner James Burbage and colleagues shifted their wooden ‘O’ to the south of the river, after an ownership dispute in the original location. A museum of Shakespeare is supposedly opening in Shoreditch this year, on the site of another 16th century theatre called The Curtain… though it’s been much delayed.

Henry VIII’s Wine Cellar: If, for some unfathomable reason, there were an award for the building that’s moved the shortest distance, then this would win. It’s an old cellar room from Cardinal Wolsey’s York Place, later Henry VIII’s Whitehall Palace (Wolf Hall fans will know all about the transition). The room is one of the few surviving Tudor fragments in Whitehall. Unfortunately, it found itself in precisely the wrong place when the Ministry of Defence building went up in the 1940s. Even back then, drilling through a Tudor interior was frowned upon on heritage grounds. So the whole 1,000 tonne structure was jacked into a slightly different location a few metres to the right. It’s almost impossible to visit, unless you have security clearance or exceptional levels of stealth.

Kilmorey Mausoleum: Tombs and their occupants do not always stay put in this city. Bunhill Fields, for example, gets its name from a cache of bones, reinterred here in the 16th century after a clear-out of St Paul’s charnel house. Later, numerous overcrowded City churchyards were skimmed of their dead, who were reburied in the City of London Cemetery or Brookwood. The grand, Egyptian-style Kilmorey Mausoleum is a special case, for it has moved on two occasions. It was originally constructed in the 1850s in Brompton Cemetery, to house the earthly remains of Priscilla Hoste, mistress of the 2nd Earl of Kilmorey. The tomb then followed the Earl around, first to his home at Woburn Park near Weybridge and then, just a few years later, to St Margaret’s near Richmond. The Earl was eventually entombed with his beloved, and the pair remain at St Margaret’s today.

King’s Cross Gasholders: The railway lands behind King’s Cross once hosted 10 gas-holders, huge drums for the storage and distribution of coal gas. These were dismantled as the area de-industrialised. The last ones disappeared in 2011, but soon returned for a remarkable afterlife. So-called Gasholder 8 was moved a few hundred metres north (after a sojourn in Yorkshire for restoration) and now contains a disc-shaped park. Three others were re-erected nextdoor and now contain unaffordable apartments.

Marble Arch: John Nash’s ceremonial gateway was initially built to stand outside Buckingham Palace, and was completed in 1833. It lasted little more than a decade. In 1847, the Palace was once again remodelled and the arch had to come down to make space. The arch was reconstructed to the north-east corner of Hyde Park, close to the site of the old Tyburn gallows. It would go on to give its name to the local tube station, though it has never quite settled as an area name in the same way as, say, Crystal Palace.

Old Waterloo Bridge: The original Waterloo Bridge went up in 1810 but soon encountered structural problems. It was replaced in the 1930s by the current bridge, designed by Giles Gilbert Scott. The old bridge then scattered to the four winds, with fragments sent to places as diverse as Kenya, Australia and, um, Belsize Park. I maintain a list of all the known locations here, should you be interested.

Prince Albert’s Model Cottage: Skulking in the bushes along the north-western side of Kennington Park is a simple Victorian residential unit, too small to be called a block. This is a ‘model cottage’, designed by Henry Roberts as an adjunct to the Great Exhibition of 1851, with significant oversight from Prince Albert. The aim was to demonstrate how comfortable lodgings could be inexpensively constructed for the working class. The ‘cottage’ actually contained enough living space for four separate families, and even featured an indoor toilet — very rare at the time. The cottage was displayed a little outside the Crystal Palace, near the Knightsbridge barracks. It was dismantled at the same time as the great glass building, and relocated to Kennington thereafter. It’s since been used by park wardens and, latterly, by the Trees for Cities charity.

Rotunda, The: Walk across Woolwich Common and you might spot a peculiar soaring roof, like a lead-lined circus big top. This is the Rotunda, a circular building that once accommodated the Royal Artillery Museum in this most martial of London’s quarters. It started life some ten miles away, however, overlooking The Mall at Carlton House. The Rotunda was designed by John Nash as an event space for the Prince Regent, and its parties included a big knees-up for the Duke of Wellington in 1814. After four years at Carlton House, the Prince grew sick of it, and ordered that it should be moved to Woolwich to serve as a museum of the artillery. And so it was, until 2001 when the museum closed. It currently lies empty.

St Andrew’s, Wells Street: This thrusting church once dominated the Marylebone skyline (if there is such a thing). It attracted a fashionable congregation, including Prime Minister William Gladstone. By the 20th century, the area had lost much of its residential population, and church attendance dwindled. At the same time, the suburbs were booming, and needed new places of worship. The decision was made to save the building by transporting it, stone by stone, to the northern suburb of Kingbury, where it stands to this day.

St Antholin’s: A Wren church in the centre of the Square Mile that no longer exists. The Blitz was not the culprit on this one. St Antholin’s was demolished in 1875 for road improvements. One sizeable fragment survives, however. The top of the spire had been replaced in 1829, with the old masonry going to wealthy printer Robert Harrild. He erected it in his back garden at Forest Hill in south London. It remains there to this day, although it’s now surrounded by a housing estate. Harrild, incidentally, is remembered in the excellent Harrild & Sons bar on Farringdon Street.

St Luke’s Euston: John Johnson is best remembered for co-designing Alexandria Palace, but he also gifted a neat little gothic church to Euston Road. It was to last just five years. In 1866, the still-new church was dismantled to make way for St Pancras station. Happily, the building was given a new lease of life over in Wanstead, east London, where it remains in service as the United Reformed Church. Fans of moving structures can tick two off in one go; the church stands very close to a fragment of Old Waterloo Bridge, which supports a bust of Winston Churchill on the High Street.

St Mary Aldermanbury: If you seek evidence that the City of London is completely nuts (in a good way), then consider that it was once home to a church called St Mary Aldermanbury and an unrelatd church called St Mary Aldermary, only a five minute walk away. (See also St Mary Woolnoth and St Mary Woolchurch.) Aldermary is still there, but its near namesake has fled to Fulton Missouri. Heavily bombed in the war, the shell of this Wren building was shipped to the Midwest in 1966 and rebuilt. Today it serves as a museum and memorial to Winston Churchill, who gave his “Iron Curtain” speech in Fulton.

St Pancras Waterpoint: A gothic industrial block designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott to furnish St Panc’s steam engines with water. It became redundant in the 20th century but was left unmolested by the side of the station. By 2001, it was a prized piece of Victorian architecture. So when the time came to expand St Pancras to accommodate Eurostar trains, the waterpoint was carefully moved to a new location overlooking the canal. It now serves as a hub for the St Pancras Cruising Club. It’s occasionally open to visits, most reliably during London Open House week in September.

Sundial column, Seven Dials: Seven Dials adjacent to Covent Garden marks the confluence of seven roads. At its centre stands a column with six sundials — the pillar itself is the gnomon for a seventh sundial. Clever, eh? It’s not the original, though. That was removed as long ago as 1773. The stones were rescued by architect James Paine and re-erected near his Surrey home in Weybridge. It’s still there. The present column was erected only in 1989, a near-replica of the Georgian structure.

Temple Bar: One of the very few London structure to move not once but twice. For centuries, Temple Bar has marked the boundary between the City of London and Westminster. East is Fleet Street, west is Stand. This frontier has always featured some kind of checkpoint, marker or gate, but the structure we know as Temple Bar today was built by Christopher Wren not long after the Great Fire. It lasted until 1878 when a combination of deterioration and traffic obstruction persuaded the City of London Corporation to dismantle it. The stones were purchased by brewer Henry Meux and re-erected at his home in Theobalds Park, Hertfordshire. There it stood, somewhat forlorn, until 2003, when it was recalled to the City as a centrepiece of the new Paternoster Square development. That’s a very succinct précis for such a richly storied building. I hope to do it justice in a future newsletter.

Temple of Mithras: Remember the hypothetical award for the shortest move by a building, which I’d previously conferred upon Henry VIII’s wine cellar? Well, this Roman survivor would also be in with a shout. The remains of the ancient temple were discovered among Blitz ruins in 1954. The discovery was huge. It redefined our understanding of Roman London and had people queuing round the block to get a peep. Alas, the Romans had built their temple inconsiderately close to where a 1950s office block was to be erected. And so the remains were carefully lifted out of their ancient abode and reassembled across the street on an uninviting podium. Happily, the temple was put back almost precisely where it came from about a decade ago, when the 50s office block was knocked down to make way for the Bloomburg Building. You can now visit it, in a free attraction called the London Mithraeum.

Wellington Clock Tower: The northern end of Borough High Street was once dominated by a huge clock tower. Built in 1854, this was one of the most notable memorials to the Duke of Wellington. Sadly, the coming of the railway viaducts ruined its appearance. The tower was also becoming something of a traffic blocker. And so, in 1867, it was torn down. Its saviour was to be George Burt of the Mowlem firm. The company imported stone from Swanage in Dorset for construction projects, but needed ballast for the return trip. Burt got into the habit of selecting unusual architectural stone for his ballast, including the blocks of the clock tower. He sailed it back to Swanage and there had it rebuilt on the water front. He pulled this trick many times. If you visit Swanage today (and I would commend it to any Londonophile), then you’ll find the place littered with remnants of old London. I made a reasonably comprehensive list a couple of years ago. You’ll find weather vanes from Billingsgate, bollards from different parishes, and a facade from the old Mercer’s Hall (for which there is not room on my map).

Wellington Arch: The larger, if less famous, sibling of Marble Arch stands in the middle of Hyde Park Corner. For a fee, you can climb up, to find a small exhibition above the arch. Here, you’ll discover that the structure, commemorating the Iron Duke, has migrated from its original location. It hasn’t moved far, mind; about 50 metres, from the corner of Knightsbridge to the top of Constitution Hill in 1883. At the same time, the sculpture on top — an oversized equestrian stature of the Duke of Wellington — was shifted to Aldershot Barracks, and replaced with the Quadriga, which stands there today.

Young V&A: The former Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green has always been operated by the V&A, but the connection was once more intimate. The iron-framed building started life in South Kensington as part of the original structures of the parent museum. It shifted to Bethnal Green in 1872, and initially housed objets d’art. What the poor East Enders made of this new attraction in their midst, and the fancy coaches that would bring the rich over from the West End is a fascinating topic in its own right, which I will get around to telling in an upcoming newsletter.

Thanks for reading. As ever, please do leave a comment below, especially if you’d like to share another one of London’s buildings that have moved. And email me any time on matt@londonist.com

In my local park, Friary Park in North Finchley we have the statue of Queen Victoria which was intended for the top of the memorial to the Great Exhibition which stands at the back of the Royal Albert Hall (not to be confused with the Albert Memorial). After the death of Albert Queen Victoria insisted that a statue of Albert should stand on top of the memorial so her own statue was consigned to the Royal Horticultural Society's Garden nearby. When the gardens closed Victoria 's statue went into storage but was later donated to our local park which opened in 1910. However, at the time nobody knew it was Queen Victoria and the statue was named Peace. A few years ago a local Historian did some research and discovered the statue's true identity.

The Russell Square cabman's shelter was originally outside the Haymarket Theatre, the theatre that the shelter’s donor, Sir Squire Bancroft was then managing. It was later moved to Leicester Square where it spent some considerable time. During this time, when the green hut was located in Leicester Square during the war, the siren was sounded and the diners made their way down to the underground air raid shelter. After the all clear, the cabbies made their way back to the shelter to finish what was left of their dinner. To their surprise, all their cabs had been destroyed by a German bomb. Amazingly, the shelter survived with just some superficial damage. The shelter vanished in the late 1980s when pedestrianisation arrived and the shelter became obsolete. The decision was then taken to move the shelter to Russell Square. The shelter was restored in 1987 and again prior to the London 2012 Olympics when it was re-sited yet again in the north-west corner of Russell Square. A plaque outside attests that this shelter was presented by Sir Squire Bancroft a famous actor/manager in 1901.