The Crystal Palace was a wonder of the world, built for the Great Exhibition of 1851. It was the largest glass building ever seen. But its architect Joseph Paxton had built another “world’s greatest glass structure” a decade earlier. The “Where?”, “What for?”, and “Why did it end up exploding?” are coming below in the main feature, but first our weekly list of upcoming London history events.

History Radar

📍✍️ POVERTY MAPS: Short notice, I’m afraid, but if you’re free tomorrow (13 April), then London Metropolitan Archives has a cracking all-day exploration of the Charles Booth poverty maps. One of the great historical treasures of London, the maps show the distribution of wealth in the late Victorian capital at the resolution of individual buildings. Other than somehow resurrecting Booth himself, the session could scarcely have a better host than historian Sarah Wise, whose books make much use of this unique resource.

📝🗣 BYRONIC ALL-DAYER: On 17 April, the British Library marks 200 years since the death of Romantic poet and historical dirtbag Lord Byron with a day celebrating his life and works. Speakers, scholars and musicians gather for the Byronic All-Dayer (coincidence that the acronym is BAD?), where topics include what Byron teaches us about democracy, and new interpretations of his work.

🌍💂🏽EMPIREWORLD: On the same day, author and journalist Sathnam Sanghera takes part in an online event for the National Archives, discussing his latest book, Empireworld (sequel to his barnstorming Empireland). Find out about the legacies left over from when the British Empire occupied a quarter of the planet, from religion to laws.

🤴🏻🏰 SHARDLAKE’S LONDON: CJ Sansom’s Shardlake novels offer a brilliant insight into London’s Tudor period. Follow in the footsteps of the fictional lawyer-turned-reluctant-detective Matthew Shardlake, in this free talk about the tensions and troubles of 16th century London. Watch in person at Guildhall Library, or online.

🏠📸 BEHIND THE BLUE DOORS: See what lies Behind The Blue Doors of a distinctive Georgian building in Brixton, as a free exhibition of shots by documentary photographer Jim Grover goes on display at Lambeth Archives from 19 April. Find out the stories of the residents of the Trinity Homes Almshouse, including a former Buckingham Palace footman, and the building’s first male resident.

📗🛖 LIBERTY OVER LONDON BRIDGE: On 19 April, author Margaret Willes is at Blackheath Halls to talk about her recent book Liberty Over London Bridge, a history of Southwark and the people who have lived there, historically choosing it as a place close to the City, but beyond the City’s jurisdiction.

Crystal Palace: The Prequel

As regular readers will know, I have something of an infatuation for the Crystal Palace — the vast glass container for the 1851 Great Exhibition. Here it is in its original home of Hyde Park:

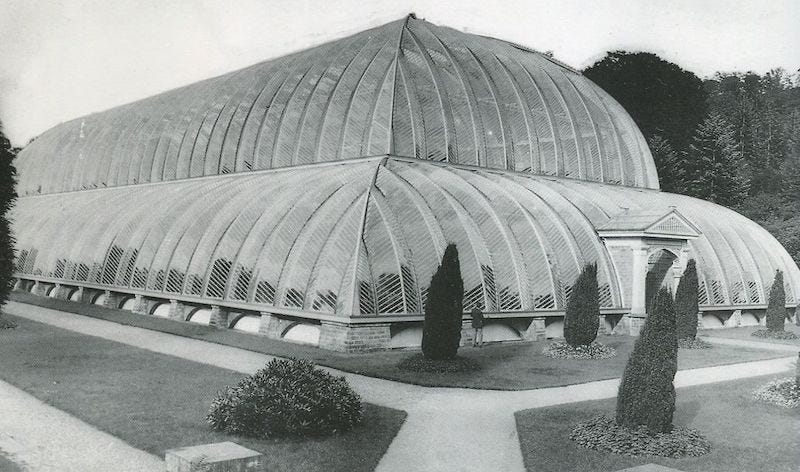

But architect Joseph Paxton didn’t just conjure this marvel out of his fuzzy side whiskers. The man had form. A decade earlier, Paxton had turned the aristocratic heads of Derbyshire with this highly original building in the gardens of Chatsworth House:

This is the Great Conservatory, the largest glass building in the world when it was completed in 1840. It measured 84 metres in length and 19 metres in height, but a better sense of the scale can be gained by noticing the tiny figure to the right of that central leylandii.

Its curving, crystalline form looks very modern, so imagine how futuristic it must have looked almost 200 years ago.

Paxton didn’t create this beaut single-handedly but worked with architect Decimus Burton. It’s not entirely clear which elements can be attributed to which man. It seems that Paxton worked out the modular construction of glass and wood, while Burton gave it architectural form. The sources are contradictory, though most contemporary accounts mention only Paxton. Either way, Paxton developed skills and experience that would become invaluable during the planning of the Crystal Palace.

The Great Conservatory was built for the 6th Duke of Devonshire, whose family have owned Chatsworth since Tudor times, and remain there to this day. The Duke wanted to create a tropical paradise in the Derbyshire Dales, complete with ferns, aquatic plants, and vibrant flowers. The conservatory was to be so large that it could accommodate a central thoroughfare wide enough for two carriages to pass.