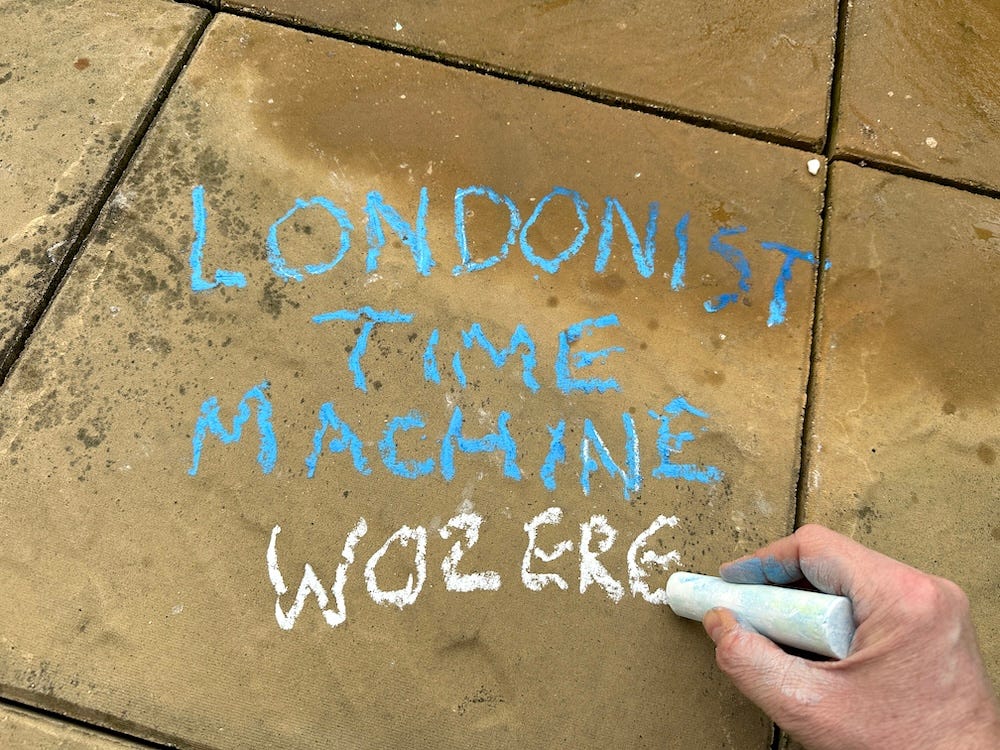

Welcome to Friday’s instalment of Londonist: Time Machine for paying subscribers, with a generous teaser for everyone else.

The urge to write on walls is as old as language. Simple “I woz ere”-style graffiti is common across cultures all over the world. The Romans particularly loved to annotate their masonry with lewd lettering or cheeky comments about their rivals. It has always been with us, and doubtless always will be. London is no exception. Indeed, our city has a little-discussed history of furtive penmanship. For today’s newsletter, I’ve chalked up a few examples from the archives, including some that are long-forgotten.

That’s for the main section. First, the History Radar:

History Radar

Upcoming events of interest to London history fans.

✍️ MAVERICKS: On 10 February, TikTok historian J Draper tells stories of mavericks throughout history at Conway Hall. Hear about an orphan kidnapped into a bizarre child-raising experiment, a child found living in the woods in Germany who was brought to the royal court in England, and the man who wrote the first account of a dinosaur, as well as other tales from Draper's book, Mavericks: Life Stories and Lessons of History’s Most Extraordinary Misfits.

🚃 LONDON'S TRAMWAYS: I love the look of the latest exhibition at the London Archives, which showcases some of the posters and artworks used to promote London's tram network in the first half of the 20th century. 40 works are on display. These include the first set of posters, commissioned in black and white, by the London County Council, and a slew of later, coloured designs. Begins 10 February and runs till 26 June.

😢 LOST LONDON: And speaking of London Archives, this week is your last chance to catch the Lost Victorian City exhibition. This small but excellent display offers rarely seen photographs of lost buildings and places, and also some of the lost trades. What became of the cats’ meat man? Ends 13 February.

🕋 SOANE AND MODERNISM: Find out why Sir John Soane has often been referred to as the "first modernist architect" in new exhibition Soane and Modernism: Make It New. Some drawings from his collection go on display for the first time ever, and there's also a look at other architects whose work has been likened to Soane's. 12 February-18 May

👩🏽🏫 HISTORY COURSE: Want to take your history-of-London prowess to the next level? Dr Matthew Green’s popular six-part course begins again on 12 February. “We will eschew dry lectures on civic administration and tired stories of Whitehall intrigues in favour of the theatre of everyday life, as explored through the places and spaces in which Londoners lived, worked, played, dreamed and died.”

🎶 RODELINDA: The Rodelinda Exhibition at Handel Hendrix House celebrates the 300th anniversary of Handel's renowned opera, which was composed in the building. The display features a portrait from 1725 of the celebrated castrato Senesino, along with an early libretto and various artefacts relevant to 18th-century opera culture. 13 February-6 July

📙 LONDON BOOKSHOP CRAWL: London Bookshop Crawl encourages you to visit as many independent bookshops as possible over the course of one weekend — with events at various shops around the capital (as well as online) to foster a community of book lovers. The aim, of course, is to support London's independent bookshops, while treating yourself to a few new reads. 14-16 February

👑 COLONEL BLOOD: Name ring a bell? He's the fella who brazenly tried to filch the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London back in 1671. During half term, Blood and his cronies return to the Tower (well, costumed actors playing them, anyway) for three daily performances, which families will enjoy. It's included in the ticket price. 15-23 February

Graffiti: A Sketchy London History

Graffiti is often dismissed as an eyesore; mindless vandalism; something to be expunged or prevented in the first place. But today’s “criminal damage” can become tomorrow’s historical curiosity. Graffiti from another era can tell us much about the fears, the dreams and the sense of humour that prevailed in previous generations. In some cases, graffiti preserves the names of Londoners who appear nowhere else in the historical record.

In today’s newsletter, I’ve pulled together a compilation of the most interesting graffiti from different centuries. Some of this is fairly well-known, others examples are drawn from long-forgotten newspaper accounts.

I’m concerning myself here with graffiti in the form of meaningful words, written or scratched onto walls. I’m not considering the (equally fascinating) realm of street art, nor the ubiquitous graffiti ‘tag’ commonly found on railway sidings.

Ye olde graffiti

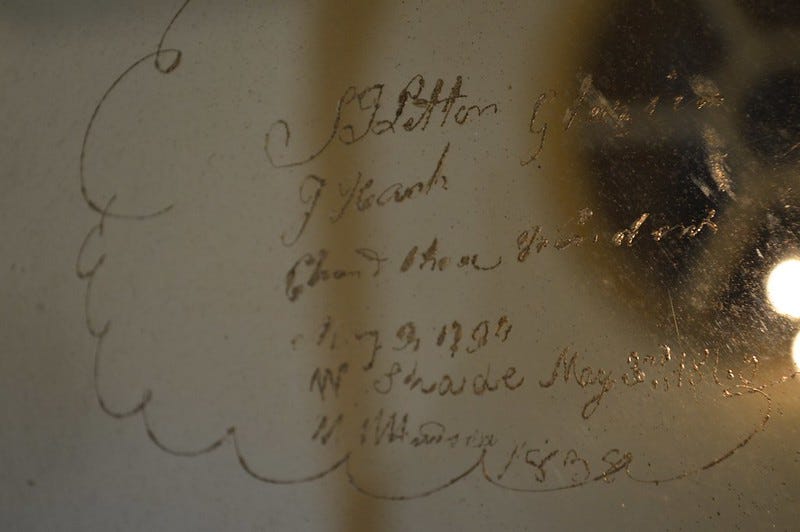

Most of London’s historic buildings contain graffiti. By age-old tradition — still observed today — stone masons and joiners will leave their marks within the fabric of the building, for discovery by future generations. In some cases, these hidden initials or surnames are the only record of these long-deceased craftsmen. I’ve been shown such marks in numerous Christopher Wren buildings. Here, for example, are some names scratched into glass inside the Old Naval College, Greenwich. They date from 1794, 1860 and 1838 (I think).

The oldest I’ve encountered is the date 1411, scratched into a door at Headstone Manor, Harrow. If genuine, these numerals were carved by a contemporary of Chaucer. Sadly, the medieval door vandal neglected to leave a name.

We can be more certain of the identities of the stone-chisellers in the Tower of London. Here, prisoners had months or years to contemplate their existence, and few outlets for creativity other than chipping away at their cell walls. Exceptional examples, carved by earls, priests and courtiers, can be found inside the Beauchamp Tower, and have been well-documented by the Gentle Author. You can even explore some of it in 3-D.

19th century scratchmarks

We might think of the Victorians as a prim and proper bunch, but graffiti was rife in a city with so many dark and smoggy corners. Graffiti of a religious nature was common, as were political statements. A possibly antisemitic graffito was one of the key pieces of evidence in the Jack the Ripper case.

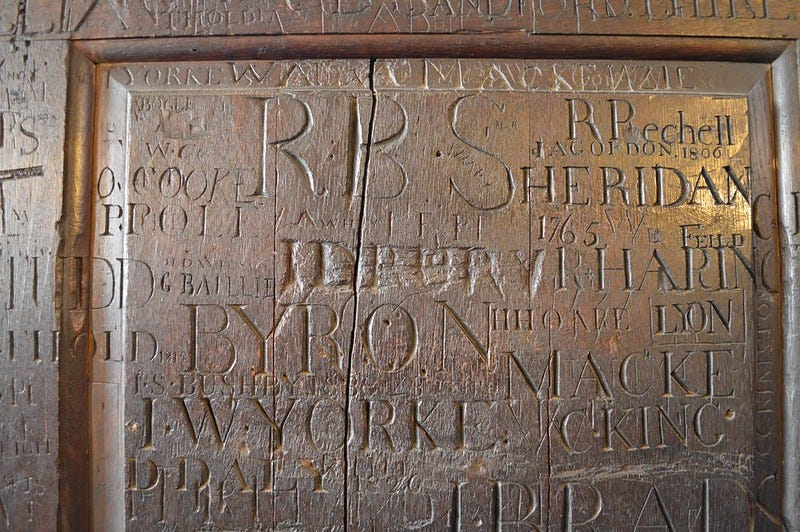

But writing on walls was not just a working-class pursuit. It could be found in the most rarified places. The Fourth Common Room at Harrow School, for example, is famous for its scratched panelling. The young Byron wrote his name here, as did Churchill and three other future Prime Ministers.

Churchill was a serial name tagger. His autograph is also scratched into the windows of the oldest house in the Square Mile, on Cloth Fair. It’s long been the tradition for celebrity visitors to add their names to the panes. Neighbour John Betjeman’s shaky signature is there, just below that of cartoonist Osbert Lancaster. Even the Queen Mum’s august etchings are reputedly up there, although the current owner of the building tells me he’s never yet spotted it.

Even the police had a go. If you look closely at the long wall in Myddleton Passage, Clerkenwell, you’ll find a series of names and initials scratched into the bricks. These are the handiwork of officers from the Finsbury division of the Metropolitan Police, who carved their names here as part of a tradition.

The first graffiti on the Underground

Remember this name: Mr Aquila John Williams. You won’t find him in any history book, but he deserves some kind of recognition as the first known person to graffiti the London underground.

In 1864, just 14 months after the opening of the Metropolitan Railway, Mr Williams was up before the magistrate accused of writing "obscene words... calculated to pollute the minds of the passengers on that railway" [Cork Examiner, 10 March 1864]. History does not record his selection of phrase. For the sake of argument, let’s assume it was some lewd wordplay involving Lord Palmerston.

Mr Williams, of 21 Harcourt Street, Marylebone, pleaded guilty and expressed his deep regret. The pioneering vandal was ordered to pay 40 shillings plus costs. In summing up, the judge said he was confident that the case's publicity "would be effectual in preventing such conduct in future." And no one ever wrote a naughty word on the tube ever again.

1930s political graffiti

After personal “I woz ere”-style messaging, the commonest form of graffiti is probably the political statement. These have always been with us, but grew more common through the 30s and 40s for obvious reasons.