Welcome to Londonist: Time Machine’s Friday edition for paying subscribers, with a nutrient-rich teaser for everyone else.

Last week, a group of 20 or so Time Machine subscribers paid a visit to Temple Bar, Christopher Wren’s ceremonial gateway, which now stands in Paternoster Square. It is drenched in history, only a little of which I have space for in this newsletter. But do read on because I reckon I’ve got at least two nourishing bits of London trivia you won’t have head before.

That’s for the main section. First, the History Radar…

P.S. I’ll be announcing a site visit to another historic location next week, for paying subscribers…

History Radar

Upcoming events for London history fans.

🙋🏽♀️ WOMEN'S HISTORY MONTH: A reminder that Women's History Month events are ongoing throughout March, celebrating the often-overlooked achievements of women, and particularly women who have fought for their right to be recognised. Here’s a round-up including shows, talks and tours.

👣 LITERARY FOOTPRINTS: The guides at Footprints of London continue their series of guided walks themed around literature, for the Literary Footprints festival. Highlights this week include a virtual tour of Samuel Johnson's life on Fleet Street, a walking tour focusing on sci-fi and dystopian fiction in which London has been destroyed, and a stroll around Waterloo, discussing its role in works of fiction.

🚂 KING’S CROSS: The station is the focus of a free talk at Guildhall Library on 17 March. Hear about the history of Lewis Cubitt's building, from its grand opening in 1852, to major redevelopment in the 21st century. Tickets to attend in person have sold out, but you can watch online.

🌳 ROMAN GARDENS: Archaeologist Dr Sadie Watson uncovers the evidence for Roman gardens in London at the RHS Lindley Late on 18 March. Head to the Lindley Library in Westminster for a talk about how archaeology and archaeobotany can help us to understand the flora and design of gardens in Roman London, and how this still influences our green spaces today.

🏰 HAMPTON COURT: From 19 March until the end of the month, Hampton Court Palace hosts the world premiere of a promenade experience. Wander through the palace after dark, accompanied by audio telling the stories of women who lived or worked there. Suffragettes, royal mistresses, queens and maids all feature, their stories told by actors including Kathryn Hunter and Miranda Richardson, and backed up by historical research.

🪶 MUSEUM LATE: The former home of Dr Samuel Johnson, located close to Fleet Street, stays open for a museum late on 20 March. Explore the 17th-century house -- the only original townhouse still standing in Gough Square -- after hours, with a drink in hand.

🕵️ DOCUMENTARY OF THE WEEK: Bernard Falk's Tour Of Hidden London first came out 50 years ago, but this cavalcade of oddities around the capital has just been republished by the BBC Archive and WHAT a treat it is. Put that Netflix series on pause, and set aside 45 minutes to enjoy Falk’s eccentric look at London life.

Inside Temple Bar

Is there an SI unit for the amount of history a building has seen? Temple Bar would be up there with the Tower of London. If we factor in its size, then this diminutive gateway near St Paul’s would quite possibly be the most densely historic structure in London.

I was thrilled recently to be granted access to Temple Bar, along with 20 Time Machine readers. We were treated to an absorbing introduction by the building’s custodian Grant Smith, followed by a look inside the Bar itself.

Time at the Bar

Let’s start with an utterly useless bit of trivia, which I noticed while idling around beside the Bar. There’s a spot in Paternoster Square that — so far as I know — is the only place in London where you can see statues of two Queens in one gaze. Here it is:

Queen Anne’s likeness can be seen in the distance, outside St Paul’s, if you squint a bit. Meanwhile, up on Temple Bar itself, we can spy a statue of Anne of Denmark, wife of James VI and I. (Although some say she’s meant to be Elizabeth I… I”m not so sure.) The other statues on Temple Bar, since you ask, are the first two Charleses and the previously mentioned James.

There. Now I’ve got that out of my system, let’s turn to more weighty matters. The first thing to know about Temple Bar is that it’s not where it’s supposed to be. The gateway looks perfectly at home, standing beside two other Christopher Wren buildings and serving as a portal to Paternoster Square. But it was only placed here in 2004. Wren designed it to stand 10 minutes’ walk away to the west, at the point where Fleet Street becomes Strand, and the City becomes Westminster.

Here it was erected between 1670 and 1672 to replace a largely wooden structure of antiquity. Looking at those dates, and the word ‘wooden’, you’d be forgiven for jumping to conclusions that involves the Great Fire of 1666. Not so fast. The fire never quite reached Temple Bar. Rather, the gateway was replaced as part of the general works to restore and improve the City in the wake of the fire.

This does seem a bit curious to me. Why was a gateway built so soon after the fire, when other, more useful buildings might have taken precedence for the building materials and manpower? I’m told, by the knowledgable Grant Smith at Temple Bar, that the gateway was planned before the fire, as part of the Road Widening Act of 1662. So it was already in the works. Still, it feels odd to me that, in the wake of such an immense catastrophe as the Great Fire, a richly decorated gateway would be among the first significant buildings to go up. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Since time immemorial, Temple Bar has been a ceremonial stopping point. It’s often written that the monarch must pause here and request permission of the Lord Mayor to enter the City. That’s not quite true. Rather, the Lord Mayor offers the monarch protection, symbolised by a pearl-encrusted sword. Here’s Her Late Majesty doing just that, as depicted in a painting at Ironmongers’ Hall.

Razing the Bar

Christopher Wren’s Temple Bar remained in situ for more than 200 years. Given that its ceremonial role was only occasional, it found ample time to multitask. Memorably, its roof was used to display the spiked remains of traitors and other members of the hanged-drawn-and-quartered community. Anyone passing beneath the arch up to the mid-18th century might admire a series of tar-coated heads, affixed to the roof on spears. The last ghastly ornament of this nature was the head of Frances Townley, a Catholic supporter of the exiled House of Stuart. His head was detached from his body and placed on the Bar in 1746, but later removed by relatives.

Temple Bar also found use as a storage space. During the 19th century, the neighbouring Child’s Bank stowed its ledgers within the structure, as can be seen in this illustration from the 1870s. Unfortunately, Wren had not designed the building to carry any great weight, and the mass of the banking tomes put pressure on the central arch. This, coupled with the demolition of supporting buildings to construct the Law Courts in the 1870s compromised the structure. Photos after this time show the gateway propped up with supports.

The building was structurally unsound, but it was also becoming something of a traffic hazard. As early as 1854, a petition was circulated calling for its demolition. The shoring up work shown in the photo only added to the problem, by placing an upright in the centre of the carriageway. And so, sadly, in 1878, the entire structure was taken apart in a matter of days.

Incidentally, a tantalising aside in the syndicated press suggests that the interior stonework might have been much older than the Wren structure:

“… A large portion of the rubbled walling shews that it formed parts of other buildings before it was used in the construction of the bar much of it shewing bold mouldings and fine carvings. This material, therefore, would be of ancient date”.

The wandering landmark

This was not the end of the story. After its demolition, the gateway was moved to “vacant ground in the Farringdon Road” (some sources say Farringdon Street). Meanwhile, the roadway was widened, and then partially obstructed again by a deliciously ornate dragon-on-a-pedestal designed by the great Horace Jones. It’s still there, marking the boundary of the City and Westminster.

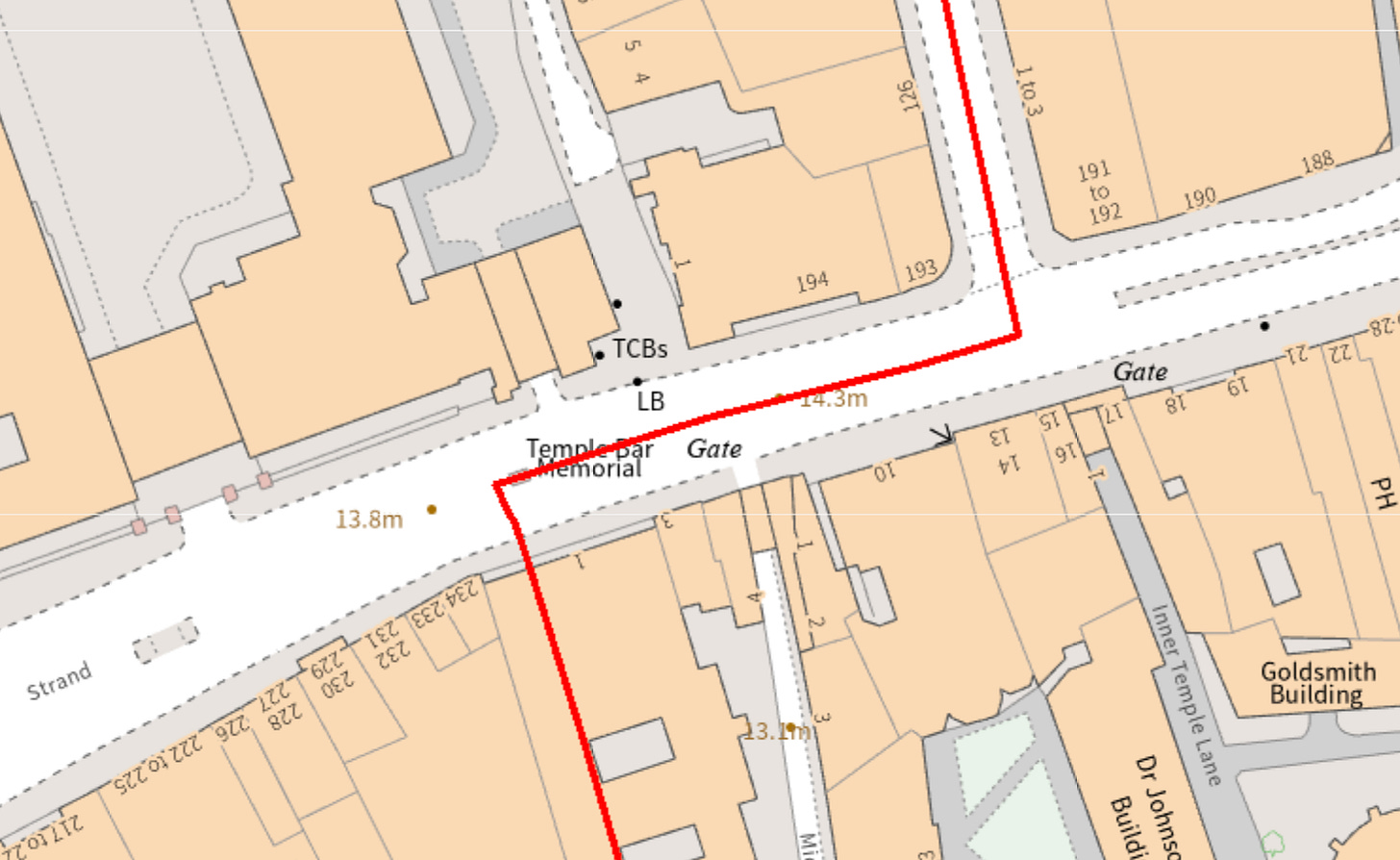

Or does it? Look at this map from the City of London’s website:

As you can see, the official boundary (red) is at the Temple Bar memorial for the southern side of the carriageway. However, if you’re heading into the City from Westminster (towards the right, on the map), you have to go as far as Chancery Lane before you hit the boundary line. I wonder if this is taken into account when the monarch pauses to accept the Lord Mayor’s sword?

Anyhow, back to Temple Bar. What would become of the old structure? It was always intended that it would be re-erected somewhere else. The stones were carefully numbered to help with the jigsaw. But nobody seems to have had a plan.

All kinds of rumours flew around in the press. It was at one time suggested that Horace Jones was to build a giant obelisk in Epping Forest from the stones, or perhaps in West Ham Park. Another newspaper rumour had the structure moving to Battersea to front a new palace. Perhaps it could be used as an ornamental gateway into the Temple from the recently built Embankment? In the event, the stones languished in the Farringdon junk yard for a full decade, before they were purchased by prominent brewers, the Meux family. They had it re-erected at their country estate of Theobalds Park, near Cheshunt. The cost, £200.

Here the Bar remained for more than a century. Winston Churchill and the Prince of Wales were apparently both entertained inside its single room. But as the century wore on, it became an increasingly unloved bauble, slightly delapidated. Then, as the 21st century got into gear, the structure was moved for a third occasion. This time, it was coming home to the City of London, as the centrepiece for the new Paternoster Square development. Here it was rebuilt in 2004. The cost, more than £3 million.