An Historical Unusualness for Every London Borough (Part 2)

As the Boroughs turn 60, I'm digging up my favourite trivia.

Welcome to Londonist: Time Machine’s Friday edition for paying subscribers, with a toothsome teaser for everyone else. No History Radar again this week… I’m still supposedly on Easter holidays. It shall return next Friday.

Greater London and the 32 London Boroughs are 60 years old this month (April 2025). To mark the occasion, I’ve put together an historical curiosity for ever one of the the boroughs, spread over four newsletters. Today, we wander from Enfield to Hillingdon, taking in more familiar boroughs such as Greenwich and Hackney.

Read Part 1 here.

Enfield

Where was King Arthur’s Camelot? One unlikely theory puts it within the London Borough of Enfield. Head to the northern fringes of Trent Country Park and you might chance across an ancient landscape feature known as Camlet Moat. It is probably a medieval earthwork, built to serve the royal hunting grounds of Enfield Chase, but it could be older. Its name is intriguingly close to Camelot and, indeed, the area is recorded as 'the Manor of Camelot' in 1440. Is this a folk memory from Arthurian times? Was this humble ditch once home to the Knights of the Round Table (who reputedly “dance whenever they’re able”)? Probably not. Camelot and its noble denizens were almost certainly a myth. Still, Enfield has form when it comes to legendary beings. Its coat of arms features an obscure heraldic beast known as an enfield. They would be easy to spot in the wild. Wikipedia describes the enfield as sporting “the head of a fox, the forelegs of an eagle, the chest of a hound but the rest of the body like a lion and the hindlegs and tail of a wolf”.

Greenwich

Christopher Wren’s Old Royal Naval College is rightly famous around the world for its grand baroque architecture. But how many people know that the Greenwich landmark once housed a nuclear reactor? During the 1960s, the Royal Navy installed a 10-kilowatt nuclear reactor nicknamed JASON in the basement of the King William Building, as a top-secret training centre for nuclear submariners. It was finally decommissioned and dismantled in the late 1990s (I was living a few hundred metres away and had no idea). Apparently, 270 tonnes of nuclear waste were removed from the site — surely a first (and hopefully last) for a Grade I-listed building.

Hackney

A-list authors Edgar Allan Poe and Daniel Defoe not only had rhyming surnames, they also lived on the same Hackney street, about a minute’s walk (and 100 years) apart. Poe, the American master of the the uncanny, spent five years of his childhood in England, including a stint at Manor House School in Stoke Newington. Today, the building is a fancy homeware shop, but it carries three memorials to the author: two plaques and cantilevered bust. In a macabre addendum, this stretch of the high street is in the news, right as I’m typing these words, after scaffolding collapsed on the adjacent library. A more pun-inclined writer than myself might have called it The Fall of the House of Hush-er.

Defoe, meanwhile, spent the last 20 years of his life in a grand home a little to the east (explored in minute detail here). The Robinson Crusoe author is remembered with a blue plaque at the site. Defoe’s grave can be found just south of the borough in Bunhill Fields, close to William Blake’s final resting place. Meanwhile, his original headstone is in Hackney Museum.

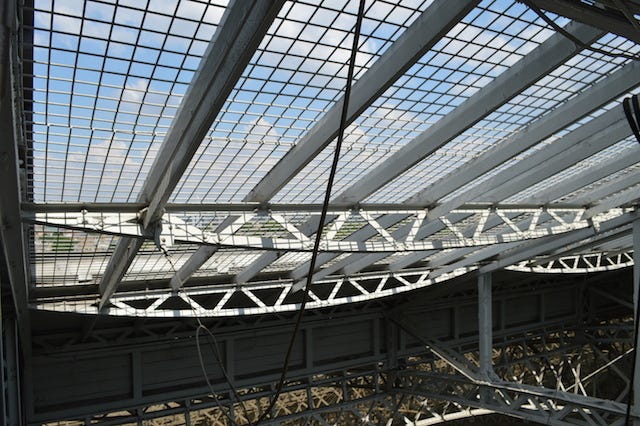

Hammersmith and Fulham

So I was climbing over the roof of the Olympia exhibition centre one day, when a disturbing fact was revealed to me. The great building’s main roof is partially retractable. At the push of a button, a sizeable portion of the apex withdraws, leaving the event space open to the skies. Very few people know about this… even the building’s marketing manager, who’d clambered up there with me, was surprised at this. There can’t be many Grade II-listed buildings with an hydraulic roof-retraction system.