London's Sorriest Corner?

The "neglected Golgotha" that's been hit by lightning, murder, grave-robbery and a rocket.

Welcome to the Friday edition of Londonist: Time Machine for paying subscribers, with a nourishing teaser for everyone else.

Some parts of London never change. While buildings come and go, the overall essence or character of a place can persist over decades or centuries. So Peter Ackroyd reckons, anyway. If any location deserves that reputation, then it’s Whitfield Gardens. This acre of land off Tottenham Court Road has seen more than its fair share of woe, over many generations. Today, I’m tracing its unenviable history from a tragic pond to a major bomb site.

That’s for the main section. First, the History Radar:

History Radar

Upcoming events of interest to London history fans.

🪑STOREHOUSE: It's the first full week of opening for V&A East Storehouse, a jaw-droppingly impressive open-access archive in Hackney Wick, brimming with half a million eclectic artefacts. Objects come from all over the world, but include several that touch on London’s history, such as a fragment of the demolished Robin Hood Gardens. It’s free to visit.

🏊🏻♀️ SWIMMING AND THE CITY: As part of London Festival of Architecture, and tying in with the current Splash! exhibition, the Design Museum hosts a panel discussion on 3 June about the history of the public swimming pool and its place in civic life, from the lidos of the 1930s to the present day.

⛪️ ABBEY LATE: On 4 June, Westminster Abbey continues the VE Day 80 celebrations with a 'beyond victory' themed late opening. Keeping the doors ajar past the usual daytime hours, the Abbey hosts swing dancing classes, Windrush storytelling, poetry writing, and crafts including origami.

☠️ LITVINENKO POISONING: Also on 4 June, join journalist Luke Harding as he recounts the dramatic story of the Litvinenko poisoning, when Alexander Litvinenko was brazenly poisoned with polonium in central London, and its implications for Russia's relations with the West. This event, part of the MI5: Official Secrets collection at the National Archives, draws from a decade of investigative reporting and exclusive interviews. Online event — watch via livestream.

🚋 TRANSPORT DEPOT: If you’ve never been to London Transport Museum’s depot in Acton, then bend every effort to go over the weekend of 6-8 June. The depot only opens a few times each year. It’s like the main museum, but ten times larger, with all manner of trains, buses, trams, old signage and other London transport paraphernalia to admire.

🪴 LONDON OPEN GARDENS: London Open Gardens Weekend (7-8 June) is a chance to explore the city's (often historic) green spaces via open days, tours and talks. They range from allotments, to small private gardens, to the likes of Eaton Square Garden, usually only accessible to residents with a key. In all, over 100 places take part this year.

🛡️ BARNET MEDIEVAL FESTIVAL: Also on 7-8 June, see re-enactments of the Battles of Barnet of 1471 and the Second Battle of St Albans 1461, as well as displays by the gunners, archers and mounted knights at this year's Barnet Medieval Festival. There's also a medieval market, craft displays and an exhibition of medieval art. Note there's a new venue for 2025: the wonderful Lewis of London ice cream farm, just north of Barnet.

🗺️ LONDON MAP FAIR: The largest antique map fair in Europe, London Map Fair (7-8 June) unfolds at the Royal Geographical Society in South Ken today, with cartography ranging from the 15th-20th centuries, and costing between £10 and £100,000. Whether you're looking for something to transform your living room, or just want a free nosey around, everyone's welcome. It's on again tomorrow.

🚽 CROSSNESS LIVE HISTORY: On 8 June, visit Crossness Pumping Station in Abbey Wood for an interactive mystery theatre event. The family-friendly adventure is set in 1865, when London's new sewage system was about to be unveiled, and it's up to you to solve puzzles, learning about the building's history as you go.

🚌 HERITAGE BUSES: London Bus Museum's semi-regular heritage day on 8 June sees buses dating from the 1950s-70s ply the 418 route between Epsom and Kingston. Just turn up along the route and wait for a RT-Type or original Routemaster to come along. You can board for free, and might even get a facsimile ticket to keep if there's a conductor on board.

London’s Sorriest Corner?

What’s the last thing you expect to happen to you at church?

“Mr. Goodson, a master-taylor in Craven-buildings [Drury Lane], being at the late Mr. Whitefield's chapel in Tottenham-court road, was struck dead by a flash of lightening; the studs in his sleeves were melted, his shirt was burnt, and the hair on one side of his head.” - Caledonian Mercury (syndicated), 30 March 1772

Bartholomew Goodson was struck by lightning, during divine service. Not only that, but his fate seems oddly specific — a master tailor getting fried until his buttons melted. Not only that, but one of the world’s leading authorities on atmospheric electricity died that very same day (22 March 1772), a couple of miles away in Spitalfields. God moves in mysterious ways.

The lightning strike was no idle hearsay. Three gentlemen of the Royal Society were in attendance and even got a scientific paper out of it, complete with diagram. They found that the lightning bolt had been attracted to a pineapple-shaped finial on the roof, which was “shivered into very small fragments.” The electricity then conducted down through the building into the unfortunate tailor’s head. He left behind “a wife and two children in distressed circumstances, who were entirely dependent on his labour”. Goodson was buried in the churchyard just metres from the scene of his electrocution. He might lie there still.

Then again, probably not. The one acre of land where Whitfield’s (sometimes Whitefield’s) Chapel once stood is among the most turbulent sites in London. You probably know it. It’s that peculiar open space mid-way along Tottenham Court Road, just north of Goodge Street station:

Today, it’s called Whitfield Gardens, though it lacks any turf. (As does Fitzrovia in general; nearby Crabtree Fields is the only bit of publicly accessible grass, and that’s currently closed for re-landscaping.) This former graveyard is now paved over with flagstones. 250 years ago, however, these were the verdant limits of London. It was here, in 1756, that the celebrated evangelist George Whitfield chose to build his third tabernacle. As a non-conformist, Whitfield was often at loggerheads with the Anglican church. Hence, he’d been looking for somewhere well away from the central parishes to establish his church. This was his plot of choice:

Now, if you were presented with the map above in Sim City or some other town-planning computer game, where would you place your new church? Whitfield opted for the least auspicious spot. He took out a lease on the field containing that Africa-shaped pond. The pool was known as the ‘little sea’ or ‘little deep’ at the time, and it came with a woeful reputation. In 1735, a young apprentice was fished out of the pond, quite dead. Heavy stones were found in his pockets. In 1755, just months before Whitfield gained the lease, another young man was found drowned in the pool, “the Misfortune was occasioned by a Matter of Love”. This was not prime real estate.

Whitfield drained his plot and began to construct his tabernacle. As a dissenting preacher, he was unable to get the ground consecrated through the Anglican church. According to legend, he had a cart-load of blessed soil brought over from one of the City of London churches, which he then covertly sprinkled around the grounds. Consecration by stealth. In the gardens, which would become the churchyard, he erected an epitaph: “Stop giddy World, and consider this Place”.

270 years later, here we are taking up that invitation.

Whitfield had a curious career. He’d been one of the key players in John Wesley’s Methodist movement, though he’d since parted ways and was preaching his own flavour of evangelical non-conformism. He was a celebrated orator, attracting crowds that could sometimes reach the tens of thousands, including such luminaries as Horace Walpole and David Garrick. But he also had a dark side. Whitfield made several voyages to America, where he acquired a plantation and became a slaveholder. He would often preach to enslaved groups, and spoke frequently against their mistreatment. Yet he never decried the slave trade itself, and benefited from forced labour.

His London orations were wildly popular, and could often get rowdy. In 1766, two men “very genteelly dressed” were locked up after “breeding a riot” in the church. Accounts of pickpocketing among the congregation were common.

Whitfield died in 1770, but his church continued. We get a good glimpse of the chapel in the 1799 Horwood plan of London. Here we see the original square tabernacle, with its octagonal extension built just a few years later. Open land to the north and south served as twin burial grounds for Whitfield’s flock (as well as his wife Elizabeth, who died in 1768).

Despite Whitfield’s zealous, uplifting energies, the plot of land would not shake off its tragic associations. Vestiges of the old pond still remained around the building, prompting an ongoing battle with subsidence. In 1768, an old man was fished from a vestige of the pond, repeating the fate of the two drowned apprentices. In 1785, a man called John Fray caught pickpocket Thomas Waking practicing his light-fingered arts on Tottenham Court Road. He proceeded to throw the thief into the Whitfield pond, where the lad got into difficulty and drowned. Fray was later convicted of manslaughter.

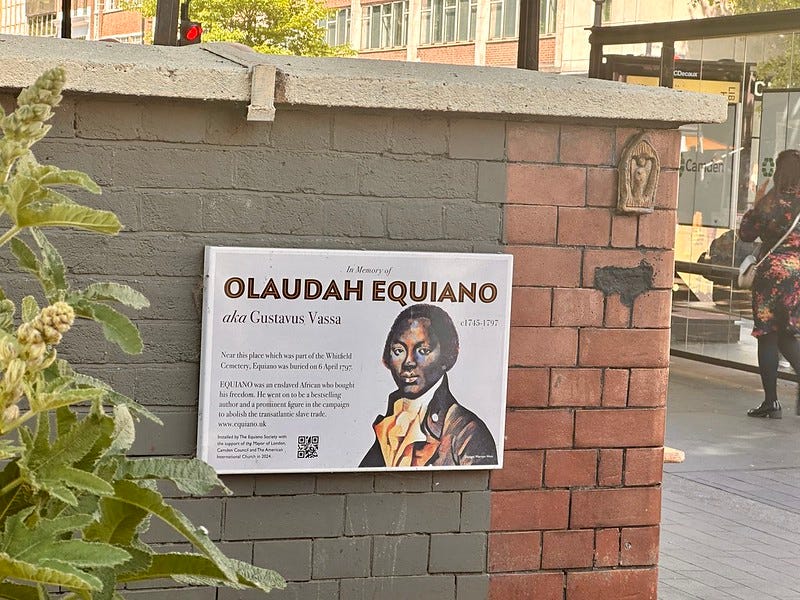

All this time, the adjacent church yards were filling up with bodies. These included the noted abolitionist Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797). Himself a Black former slave, Equiano lived locally and had dabbled in Methodism and Evangelism. He probably worshiped at the tabernacle, and it was the natural burial place when he died in 1797.

Equiano might not have remained underground for long. The churchyard was a notorious spot for grave robbers, seeking recently deceased bodies to sell to surgeons. The year after Equiano’s burial, the Kentish Gazette describes a scene that would make the swimming pool in Poltergeist look like a wildflower meadow: