One Corner, Three Histories

The terrible explosion, the world religion, and the football team.

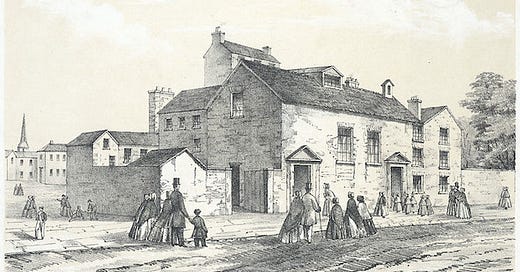

This is Bunhill Fields just north of the City of London. It is cult famous. People flock here in search of the graves of William Blake, John Bunyan and Daniel Defoe, among other religious dissenters.

Less famous — indeed, almost forgotten — is the tremendous explosion that rocked the area in 1716. Seventeen people were killed in what was…