Welcome to Londonist: Time Machine, the newsletter for London history.

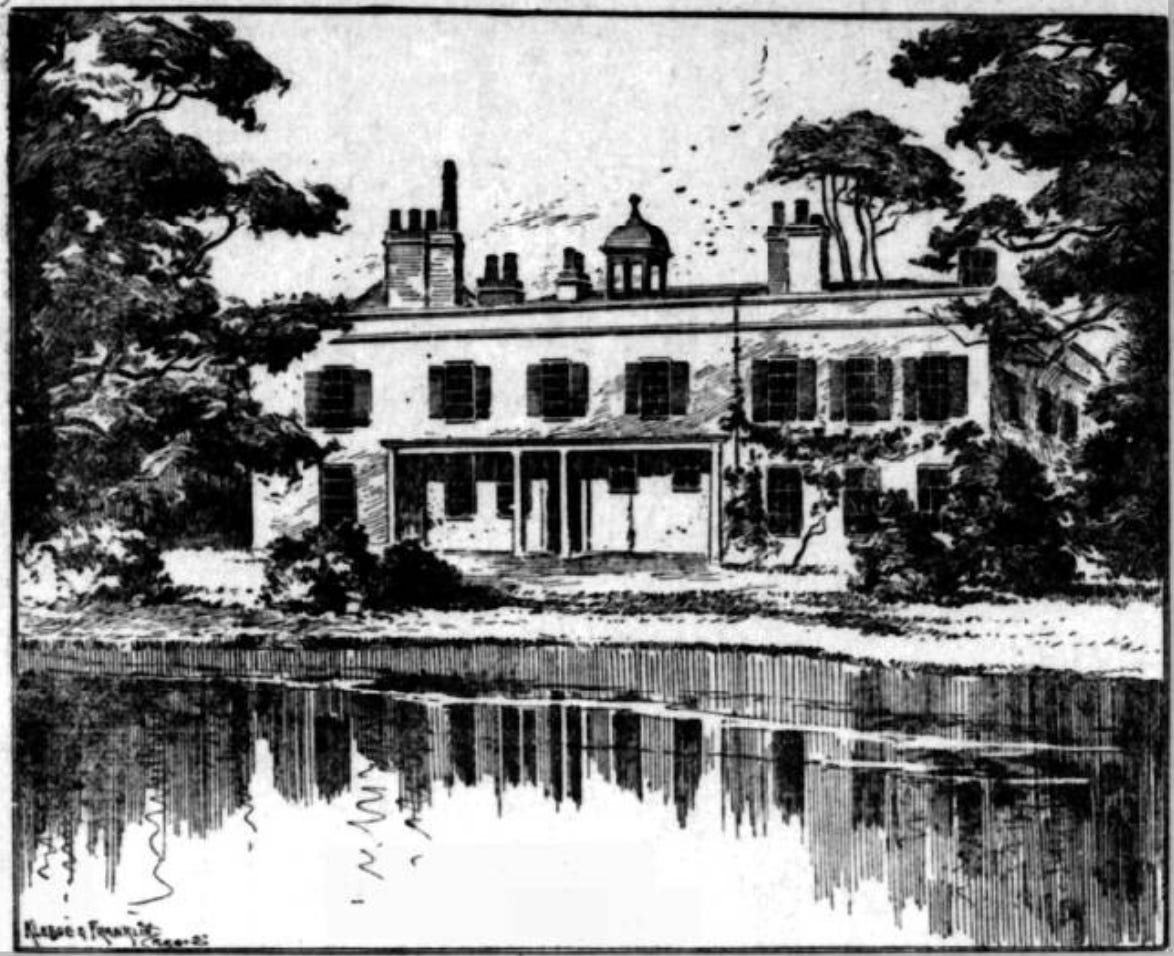

Hands up if you can identify this Tudor confection?

I’m not seeing many hands go up. Anyone? Ah, a few at the back. Locals, I presume.

There are at least two reasons why the treasure box called Broomfield House is under-appreciated. First, the years have not been kind. This is the same view today 👇. The Tudor estate’s in a chewed-up state, for reasons we’ll come to shortly. I suspect it does not suffer from a surfeit of Instagrammers.

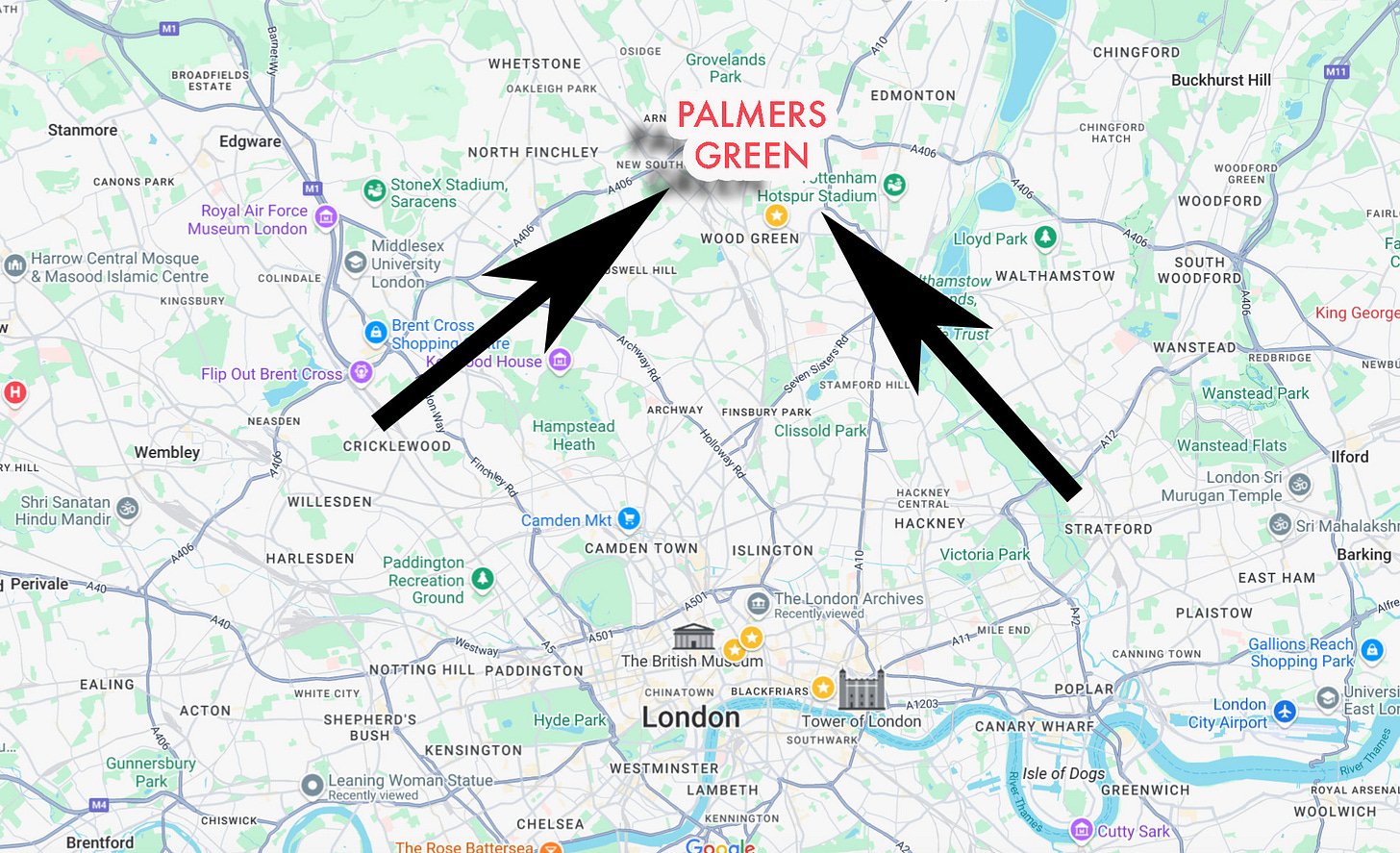

The second reason you might not have heard of Broomfield House is that it is in Palmers Green. Very few people go to Palmers Green. “Is that down near Fulham?” puzzled my wife. “Never heard of it,” rejoined my neighbour. Even I had not been to Palmers Green, despite having spent 20 years writing about the capital.

Perhaps because it’s not on the Tube map, Palmers Green slips between the cracks of cognisance. For those who’ve not had the pleasure, this is where Palmers Green can be found:

Palmers Green, it turns out, is a charmer of a neighbourhood: characterful high street; gem of a railway station (on the Hertford Loop line), with a conjoined-gem of a cafe (The Yard); and an historic old pub (The Fox). You’ve probably seen Palmers Green in the movies. For some reason, the makers of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban directed the Knight Bus along Palmers Green high-street.

There’s real magic here, too. I give you the gorgeous Broomfield Park:

These green and pleasant lands were once the grounds of Broomfield House. Wander around and you’ll find 18th century ponds, magnificent mature trees, a bandstand, sports facilities, one of the first model-boating lakes in the country, a peace garden and that glorious view of Alexandra Palace.

What’s missing is the house. It’s still there — partially — but a series of unfortunate events have left it charred, crumbling and cloaked in scaffolding. It’s a sorry situation for a building that has stood for almost half a millennium, and which was once the centre of community.

What was Broomfield House, anyway?

Broomfield House is one of those buildings whose age is hard to describe. Its wooden-framed nucleus was hammered together at some point in the 16th century, probably around 1550. It was much expanded over the ensuing centuries, as successive owners made it ever-more grand. The half-timbered facade we see in the top photo is, according to Historic England “fake timberwork added by the Council in 1928-32”. In other words, it is mock-Tudor grafted onto actual Tutor, with addendums from every era in-between. Trigger’s Broom(field).

Its early origins and Frankenstein construction make it of great architectural interest. Historic England long ago gave Broomfield House a Grade II* listing, one of the highest forms of protection. Unfortunately, no heritage credentials can safeguard a building from fire. Broomfield House has suffered disastrous conflagrations on four occasions: 1984, 1993, 1994 and 2019. We’ll come to those in a bit, but first, let’s just check in on the history of this ill-fated building.

Broomfield House through time

Given that it was built some 500 years ago, the house has naturally had many owners. I won’t get bogged down in a complete chronology, because I’ll lose your attention. So here are the edited highlights.

The first owner was a leather merchant called John Bromfylde. “Aha,” you might think, “that’s where the house’s name comes from”. In fact, it’s more likely the other way round. The house, so it’s reckoned, took its name from the local "bromfield" — a field of long grass that provided hay and grazing. Our man Bromfylde then affixed the name to himself, as in “I’m John, from the fancy house called Bromfylde. You can call me John Bromfylde if you like”.

That’s what the history books and websites say (albeit in a less flippant tone). But etymology is often a mix of scholarship and guessmanship. I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s another explanation. For instance, could it not be named for a field of broom shrubs instead, given that’s how distant Bromley is supposed to have got its name?

Anyhow, by 1599 Broomfield was in the hands of Sir John Spencer, a former Lord Mayor and reputedly the richest man in England. This chap collected big houses. His other residences included Crosby Hall on Bishopsgate and Canonbury Hall in Islington, both of which will be well known to London history fans. John Spencer was no relation to the aristocratic Spencer family nor, I presume, to the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion.

The house next came to merchant Joseph Jackson. Under his family’s stewardship, the property was greatly embiggened, with the construction of a grand staircase and a series of baroque murals designed by Gerard Lanscroon. Lanscroon was no workaday interior decorator. He also contributed wall paintings to the palaces at Hampton Court and Windsor, as well as nearby Arnos Grove House. His murals of Broomfield depict various gods and heroes from Greek myth.

After a few more changes of hands, the house moved into the public realm in 1903. The local authority, Southgate Urban District council, bought the property and surrounding land to prevent their development, and turned the whole lot over to the people. The Middlesex Gazette at the time noted that the building contained “some of the finest timber to be found on the northern heights of London”. It also harboured a ghost; the shade of an old man, who’d been seen loitering about the place, sometimes on the lawn, sometimes in the wine cellar. Strange tappings were also reported.

Spectral visitations did not stop the house from being put to good use. Indeed, it was put to almost every use, including a school, a maternity home, a dental surgery, a military base, and finally, in 1925, a museum. It remained as such for the next 60 years. Then, disaster struck.

Fire and aftermath

Broomfield House effectively died on 26 August 1984. An electrical fault set fire to the roof, destroying the upper floor. Extensive damage was done to the rest of the building, and it was cordoned off from public access. The superstructure remained sound, however, and it was hoped that the local landmark could be revived. As detailed on the Council’s website, numerous attempts were made over the years, from an ominous-sounding “Prometheus Scheme” to an unsuccessful bid to appear on the BBC’s Restoration series. The money and willpower never quite came together, alas. Further fires in the 1990s — probably arson — made the task all the more daunting.

As recently as 2015, Enfield Council undertook a public consultation to look at ideas for restoring the house. The problem was not just cost (estimated then at £6-7 million), but also ancient covenants that restricted the site’s use for commercial ventures. Those restrictions effectively ruled out private money, or would have required the council to mount an expensive legal challenge. So again, the house was left waiting. A further fire in 2019 seems to have been the final nail that broke the camel’s coffin.

Very little now remains to be saved. While many walls are still standing, they are in a parlous state and it’s unlikely they can be preserved.

Sweeping changes for Broomfield

It is gutting to hear that London has effectively lost a rare Tudor building. But positive change is also coming to the area. In December 2023, a grant of over half a million pounds was secured from the National Lottery Heritage Fund (NLHF), which will be pumped into improving the park and its facilities. The successful grant application was put together by the Friends of Broomfield Park, Broomfield House Trust, The Enfield Society, Southgate District Civic Voice, and Enfield Council.

The money will also fund a study into what can be done with the site of Broomfield House. It’s almost universally agreed that the house remains will have to come down. But how best to do this? What can be salvaged? How will it be displayed or conserved? And what exactly should go on the old site by way of memorial? This report will then be presented back to NLHF as part of a follow-on bid to secure the money to make it all happen.

One part of the building that has already been saved is the Lanscroon Murals. The damaged artworks were removed from the building following the fire of 1984. Unfortunately, their initial preservation was not ideal. A conservation report undertaken in 2018 noted (and I can only read this in the voice of Douglas Adams) :

“…more detailed examination of the materials that had been applied after the fire in 1984 revealed that the first two layers of facing material were not the acid-free tissue mentioned in the early correspondence, but that they were in fact nappy liners”. Tom Organ, Arte Conservation report, 2018

One hopes they were, at least, unused nappy liners. Conservation work has since been carried out and the panels may once again be good for display, perhaps on site.

Meanwhile, the park contains a handful of other structures that have survived from previous centuries, and which you can visit any time. The most striking is the imposing gatehouse, also thought to be Tudor. You can even see hooks on the inside that would have been used to hang game. Nearby stretches of wall, a stable block and a gazebo are of Georgian vintage.

Broomfield House has now sat behind protective scaffolding for two generations. Nobody under 40 has ever seen the grand house out in the open, and now they never will.

While it awaits its next evolution, the site was recently brightened up by local artists, who painted a series of historical snapshots on the hoardings. To orbit the house today is to journey through the eons, something of which Londonist: Time Machine wholeheartedly approves.

The first mural seems to depict a future in which robots and flying saucers tend to Broomfield Park. We then, walking clockwise, go back to one of the disastrous fires; then the painting of the staircase murals; then a hunt across Enfield Chase; further back to the Stone Age forest and, eventually, the Big Bang itself.

Not many local history projects have the confidence to trace themselves back to the dawn of time and space. We can only hope that the site’s future will be equally self-assured, even if Broomfield house itself must be swept away.

My thanks to Adrian Day (who does local tours) and John Cole (Enfield Council’s community engagement officer) for showing me round the site and providing further information. Check the Friends of Broomfield Park website for details of upcoming events, including the Palmers Green Festival on 7 September. I can also recommend the Broomfield House Trust’s website for more details on the history.

Thanks for reading. As ever, I welcome comments below. And I’d love to hear from anyone who has access to other historic buildings around London, whether well-known or obscure. Contact me any time on matt@londonist.com.

🤚🤚🤚I grew up going to Broomfield Park as a child. We adored the house with its eclectic musuem that included our favourite item; a glass bee hive by a window where we could watch the bees come and go. And a cafe at the back where my first choice treat was a blackcurrant split. I wish I could remember more about the interior of the house. Dark panels, polish and for some reason, exhibits connected to Alice in Wonderland come to mind. The fires and state of the building still make me sad.

I rather like 'embiggened'. 👍