A Deep Dive Into The Colourised Copperplate

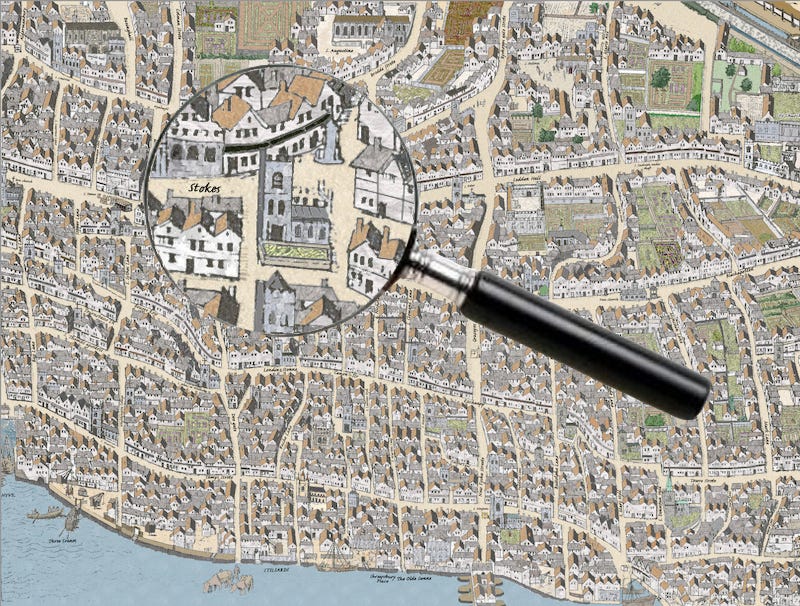

The 90 locations mentioned on the Tudor map's eastern plate.

Welcome to your Friday newsletter. And welcome to everyone. We normally only send this email out to paying subscribers, but this week’s post is so chunky and nutritious that I thought I’d send most of it out as a wider release.

You’ll remember from the last newsletter that I’ve finished my project of colouring in the three plates from the Tudor-era ‘Copperplate map’. I gave a rough overview of the panel then, but in today’s instalment I’d like to dig much deeper.

The eastern City panel contains 90 labels — streets, alleys, wharfs, churches and other buildings. Many of these labels have eroded but, with the help of the slightly later Agas map and other sources I’ve been able to restore them for this colourised version. Below, I discuss all 90 of the labels.

You’ll see the name John Stow crop up a few times. Stow (1525-1605) is the godfather of London historians. His Survey of London (first published 1598) is a key source for so much of the City’s history in this period, and it was also very useful in making sense of the Copperplate map. I’ll be revisiting his work in a later newsletter.

Anyhow, make yourself a strong cup of tea, because there’s a lot to get through. Expect a few surprises, puzzles and random speculations along the way.

In alphabetical order:

Abchurche Lane: (Centre-left) Though now brutally cut in twain by the angle of King William Street, Abchurch Lane still exists. It is named after the church of St Mary Abchurch, which can be seen, unlabelled, on the map.

Aldermanbury: (Extreme top left) One of the labels that’s particularly difficult to make out on the original, so I’ve used the modern spelling. The street survives today and is home to the fabulous Guildhall Library and New London Architecture.

Basinghall: (Top left) Running parallel to Aldermanbury (and Coleman Street in a pleasing A-B-C of roads) is Basinghall. It recalls the Bassing family who had land (and a hall) here from the 13th century.

Billiter Lane: (Centre right) Now known as Billiter Street, this narrow lane to the east of the map probably takes its name from a local bell foundry.

Blichapelton: (Extreme centre-right) One of the very few names on the Copperplate map that has utterly vanished. Blichapelton is my squinty guess at how the original engraver spelled the name — it’s too faint to be sure. Later maps refer to the street as Blanch Appleton. Once a thriving market place, it was enjoying its final hoorah at the time of this map and would soon disappear. Today, it’s simply part of Fenchurch Street, roughly where the Garden at 120 now stands.

Bookelers Bury: (Centre left) A charming ye olde way of writing Bucklersbury, still to be found as a runty stump on the modern map, just north of the Bloomberg building.

Bougge Row: (Centre left) A variant spelling of Budge Row, a medieval southern continuation of Watling Street that was wiped from the map by 20th century developments. But now it’s back. Sort of. If you walk along the commercial tunnel that is Bloomberg Arcade then you’re retreading its route.

Bow Church: (Upper centre-left) AKA St Mary-le-Bow. The church is famous for many reasons, but especially its peel. To be a true Cockney you have to be born within the sound of Bow Bells. No true Cockneys were born for about 20 years after the Blitz, as the main bell was put out of action by bomb damage.

Brodde Strete: (Centre top) Otherwise known as Broad Street, or today Old Broad Street, the oddly characterless road that forms the quickest and least interesting route from Bank to Liverpool Street. Back in the day, it was dominated by that hulking religious house you can see on the map… which we’ll come to in a bit.

Buche Lane: (Lower centre) Survives in truncated form as Bush Lane, alongside Cannon Street Station.

Buo Lane: (Far left) Nothing to do with bao buns, which were probably not a common feature of Tudor London. Rather, this is Bow Lane. This pedestrianised route is today one of the most charming in the whole City, retaining something of a medieval atmosphere, despite the modern shop signs. (Top tip… head into the tiny branch of Paul which has a hidden, half-timbered back room — although I suspect it’s pastiche — where you can feel properly medieval.)

Buttolphe Lane: (North-east of the bridge) St Buttolphe or Botolph not only has a mildly amusing name, but is also the patron saint of boundaries, both of which attributes make him my favourite saint. Four London churches were built in his name, all next to gates, and three survive. The one that doesn’t was close to Billingsgate the famous fish market that was once — probably — guarded by a water gate. Billingsgate itself can be seen on the map, just east of London Bridge where a couple of badly drawn boats are docked. Its label was presumably on the map plate to the south, which remains missing.

Byshopps gate Strete: (Top-centre) Fairly obviously this is Bishopsgate, a route that people have been strolling along since before Bishops were a thing (the name is medieval, but the gate in the wall here was Roman). The continuation of this street (and the gate) can be seen on the first panel I coloured.

Canti?: (Centre) The one outstanding mystery on the map. The word ‘Canti’ is clearly legible on the crossroads of Gracechurch Street (“Gracsyos St”) and Lombard(s) St. Above is a structure that looks like a number ‘4’, which might be a water pump. But I think the label refers to the adjacent church. This is St Benet Gracechurch Street — a name that can’t reasonably be squinted into ‘Canti’. But St Benet’s seems to have some ancient connection to Christ Church in Canterbury, which might be abbreviated to ‘Canti’. If so, I wonder why the cartographer chose to flag up an affiliation rather than the actual name. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Canon Str: (Lower centre) I was a little surprised to find Cannon Street written (clearly) as Canon Str on the Copperplate map. It’s well attested that the name comes not from a large gun or ecclesiastical canon, but as a shortening of Candlewick Street. I’d assumed it would still be closer to Candlewick in the 1550s, but here it is already abbreviated. The Agas map from a few years later has it reverting to Canwicke Street.

Colman Strete: (Top-left) Named after medieval charcoal burners, Coleman Street still runs north-south on the northern edge of the city. The label is illegible on the Copperplate, so I’ve used the Agas spelling.

Cornwell: (Centre) One of the clearer (and larger) labels on the map, as befits this major east-west route through the City. We call it Cornhill, as do most sources from the time (and earlier), though if you say the word out loud it’s easy to see how it could be heard both ways. The name comes from the corn market it once supported, which can perhaps be seen on the map. Curiously, a prominent well is also depicted, and can still be found on Cornhill today. Perhaps the street name really does derive from the Corn-well (as labelled on Copperplate) and not the Corn-hill of traditional explanation?

Crooked Lane: (North of bridge) A short and, yes, crooked Lane that was wiped off the map in the 1820s when King William Street was knocked through as an approach road to the new London Bridge.

Cry Church: (Top right) Christ Church also known as the Holy Priory was a major monastic house dating from the early 12th century. The Dissolution had brought about its end in 1532 and, by the time we see it in the Copperplate map, it was occupied by the Duke of Norfolk (hence the modern street name of Duke’s Place). The ancient name also lives on in Creechurch Lane. The neighbouring church of St Katharine Cree is not labelled on the map. Which is a pity because its stone tower is a rare City survivor from Tudor times and… oh, would you look at that; its shape and windows on the map match up with what we can still see 500 years later.

Doo gate: (North of massive paddling horses) Dowgate Hill is today something of a backwater, running alongside Cannon Street station. Historically, it was very much ‘frontwater’, a wide and important route leading up from the Thames into the centre of town. It also tracks the course of the River Walbrook which, by the time of the Copperplate, had already been covered over for a century.

Drapers Hall: (Top left-ish) This elaborate building was the new-ish headquarters of the Draper’s Company. They’d acquired the magnificent home of Thomas “Wolf Hall” Cromwell, who’d parted company with his head about 15 years before the Copperplate map was etched. Remarkably, the Drapers remain on the same spot today, albeit in a rebuilt version of the hall. (Note: I’m not entirely sure if this label even appears on the Copperplate… there’s a squiggle there that might be a label, or it might be some chimneys, that’s how degraded this area is. Still, it’s one of the most distinctive buildings on the map and worth mentioning.)

Excheappe: (North of bridge) Another way of writing Eastcheap. A traditional home of butchers, it’s today where you’ll find the Walkie Talkie building.

Fans Church: (Centre-right) Fenchurch Street is named for a church that once stood in this fen-like land. And there it is. Despite the waterlogged ground, it did not survive the Great Fire and was never rebuilt. The name lives on though, thanks to the street name, rail terminus and Monopoly board.

Fillepott Lane: (Centre, bit right) If you’ve heard of Philpot Lane at all it’s probably because of the sculpture of two tiny mice eating cheese. It’s named after former Lord Mayor John Philpot, who owned land here in the 14th century.

Fynkes Lane: (Centre) Known today as Finch Lane, this narrow cut-through from Threadneedle Street to Cornhill was originally Fynkes or Finks Lane, named for a City luminary.

Olde Swane: (Next to bridge) The label on the Copperplate has this clearly as the “Golde” Swan, but it’s almost certainly a misprint or alternative name for the Olde Swan, a well attested inn that stood on the Thames for hundreds of years. The original was wiped out with the Great Fire, but its successor came back strong as the starting point for the famous Doggett’s Coat and Badge race, as well as the annual Swan Upping tradition. A London Inheritance has an excellent article on the history of the site, focussing on Swan Stairs, which led down to the river. A Swan Lane still exists here but it’s more of an ugly duckling these days.

Gracsyos Streete: (Centre) Gracechurch Street — the road that connects London Bridge to Bishopsgate — has been a vital thoroughfare since time immemorial. It marches straight over the site of the ancient Roman forum. The name comes from the ‘Grass Church’ of St Benet (see entry for ‘Canti?’ above), which stood beside an ancient corn market. The label on the map has rendered the name closer to Gracious Street, which is also borne out in the Agas map.

Guylde Hall: (Top-left) As the centre of London’s governance, the medieval Guildhall was the most important non-religious building in the City. It’s one of the few buildings on this map panel that survives today, albeit in a heavily patched and altered form.

Harpe Lane: (Bottom-right) A tiny remnant of this street survives as Harp Lane near St Dunstan-in-the-East. It’s so unremarkable that I only stumbled across it a couple of years ago, having assumed I’d been down every turning in the Square Mile. There’s always more to learn!

HYVE.: (Bottom-left) This at-first-mysterious label can be found in the Thames to the extreme lower left of the map. It’s a label that’s been chopped in two. The prefix QUEEN- appears on the adjacent map plate, which I coloured in previously. Queenhithe is a tiny dock of rare antiquity, dating back to the time of Alfred the Great. Today it’s a protected site, off-limits to mudlarkers and foreshore wanderers.