It’s a simple enough idea: take London’s oldest map and colour it in. I’ve already published two of the three plates from the ~1557 Copperplate map, each coloured for clarity. Now, here’s the third and final instalment, showing the eastern half of the City of London. It includes Guildhall, London Bridge, London Stone, some random, massively oversized people paddling massively oversized horses in the Thames, and lots of other details I spotted by laboriously colouring in this fascinating Tudor chart.

That’s for the main section of today’s newsletter. First, a quick announcement and the History Radar…

📣📣 Thanks to everyone who’s joined the ranks of paying subscribers. Every penny helps keep this newsletter going (and, as you’ll appreciate from today’s, it’s a lot of work). Last week, paying subscribers got two exclusive newsletters. The first looked at Hilda Hewlett, the first British woman to qualify as a pilot; while the second peered into London’s history through a pint of porter. For just a fiver a month you’ll also get invitations to meetups and site tours. Give it a go!

History Radar

A roundup of upcoming events with a flavour of London history.

🇮🇪☘️ IRISH IN LONDON: Sunday is St Patrick’s Day. The history of Irish people in London is a long, rich and complex one. Fascinating, too, as I’ve learned from browsing the On Pavement Grey website. It pulls together dozens of little known stories from London’s Irish history, all mapped, and written in easily digestible snippets. These include the first official Irish ceilidh (in Bloomsbury, apparently), the very famous church named after an Irish saint, the London homes of Michael Collins and much, much more.

☘️ On the Saturday, Blue Badge guide Tony McDonnell leads the walk: A Terrible Beauty. The London Dimension to the Irish Revolution. 1916 to 1922. The walk begins at 2pm from the King Charles statue in Trafalgar Square and will look at the London side to the Easter Rising of 1916. Details here.

☘️ Rebel Tours also have four tours over the weekend that focus on the Irish people who made great contributions to London.

☘️ Alternatively (or additionally), try this immigration-focussed tour led by Laura Agustin on Sunday. The walk begins in the Fleet Ditch and works its way uphill through early Italian and Irish settlements in Saffron Hill. The walk also considers other immigrant communities who settled in this fascinating part of town.

👣📚 LITERARY FOOTPRINTS: A reminder that Footprints of London’s month long literary festival continues, with many bookish walks to enjoy. Next week’s offering includes Constable's Hampstead; Peter Ackroyd's East End; books about Waterloo; and the real-life Wolf Hall.

👗🧵JEWISH FASHION DESIGNERS: On Tuesday next week (19th) and tying in with the current Fashion City exhibition, the Museum of London Docklands stays open late for a panel discussion about the Jewish designers, makers and retailers who made London’s West End a fashion destination. The panel includes fashion and business historian Dr Liz Tregenza, and Danielle Sprecher, curator of the Westminster Menswear Archive at the University of Westminster.

🚤📖 LONDON DOCKS: Also on Tuesday 19th, photographer Niki Gorick is at Guildhall Library to talk about the regeneration of London’s Docklands. Her new book Dock Life Renewed looks at the dozens of unexpected ways in which these old industrial and maritime facilities have been transformed for work, life and play. It’s a beautiful book, for which I had the honour of writing the Introduction.

🏵🤴🏻 TUDOR HISTORY: And on 21 March, Reformation England expert Dr Lucy Wooding is at Southwark Cathedral to discuss her new book, Tudor England: A History. As well as the Tudor monarchs, Wooding tells the stories of everyday people living in cities, towns, and villages, families and communities through times of great upheaval.

Now, on with the mapping…

London’s Oldest Map, Now In Colour… Part 3

London’s oldest map, the so-called Copperplate Map, is tantalisingly incomplete. Only three surviving panels of a probable 15 are known. They are gorgeous artefacts, offering many rich insights into the Tudor city. The black and white streetscapes are so dense in detail, however, that it’s tricky to make out what’s going on.

So I’ve been colouring them in.

Here are the sections I’ve previously tackled:

The northern panel, around Moorfields and Spitalfields

The western panel, which includes St Paul’s Cathedral, Cheapside and parts of the Thames

I also published a bonus gazetteer edition as a companion to the eastern panel, exploring all of the place names labelled in the panel

The third and final section covers the eastern side of the City. Here we find the Guildhall, Leadenhall, the northern part of London Bridge, part of the City walls and dozens of churches.

Here it is, in colour for the first time:

What am I looking at?

I just wanted to include a brief recap of the history of this map for the sake of newcomers. If you read earlier parts, you can skip this section.

The so-called Copperplate map is the earliest map of of our city or, at least, the earliest to survive. Much older maps of England are known, and it’s possible that somebody sketched out a street plan of the capital that has not withstood the centuries. Slightly earlier panoramas exist, which have map-like qualities, but the Copperplate is regarded as the first true map.

Details within the map suggest that it was created some time between 1553 to 1559 — almost certainly during the reign of Queen Mary, but possibly the beginning of Elizabeth I’s reign. The cartographer is unknown, though various lines of evidence point to an artist or team of artists from the Low Countries. It was etched onto the surface of copper sheets, which were then used as master copies from which paper versions would have been printed. Wear and tear on the plates — especially the eastern city plate covered in today’s article — suggest that this happened, although no printed copy has ever been found.

Nobody suspected that the Copperplate map even existed until 1962 when, like the set-up of an adventure movie, a fragment was discovered on the back of a painting of the Tower of Babel. Cue, an international treasure hunt for further fragments. To this day, only three of the probable fifteen panels have been recovered. Two are kept at the Museum of London (including the one we’re looking at today), and the third at Dessau Art Gallery, Germany.

I do hope the Museum of London puts both of its panels in pride of place at their new Smithfield museum. They are objects not only of immense historical importance but are also beautiful to behold.

Colouring in the Eastern City panel

This was by far the most challenging of the three panels to spruce up. The available public domain images are much more faded than those for the other two panels. Buildings on this map are visually muffled. They are well on their way to joining their real-world originals: places that once were, but are no more.

I was keen to get colouring, but first I had some basic restoration work to do. I had to retrace the enfeebled rooflines, repoint a thousand chimneys and assay each row for missing doors, windows and half-timbers that had half-vanished. The task was meatier than a Tudor banquet.

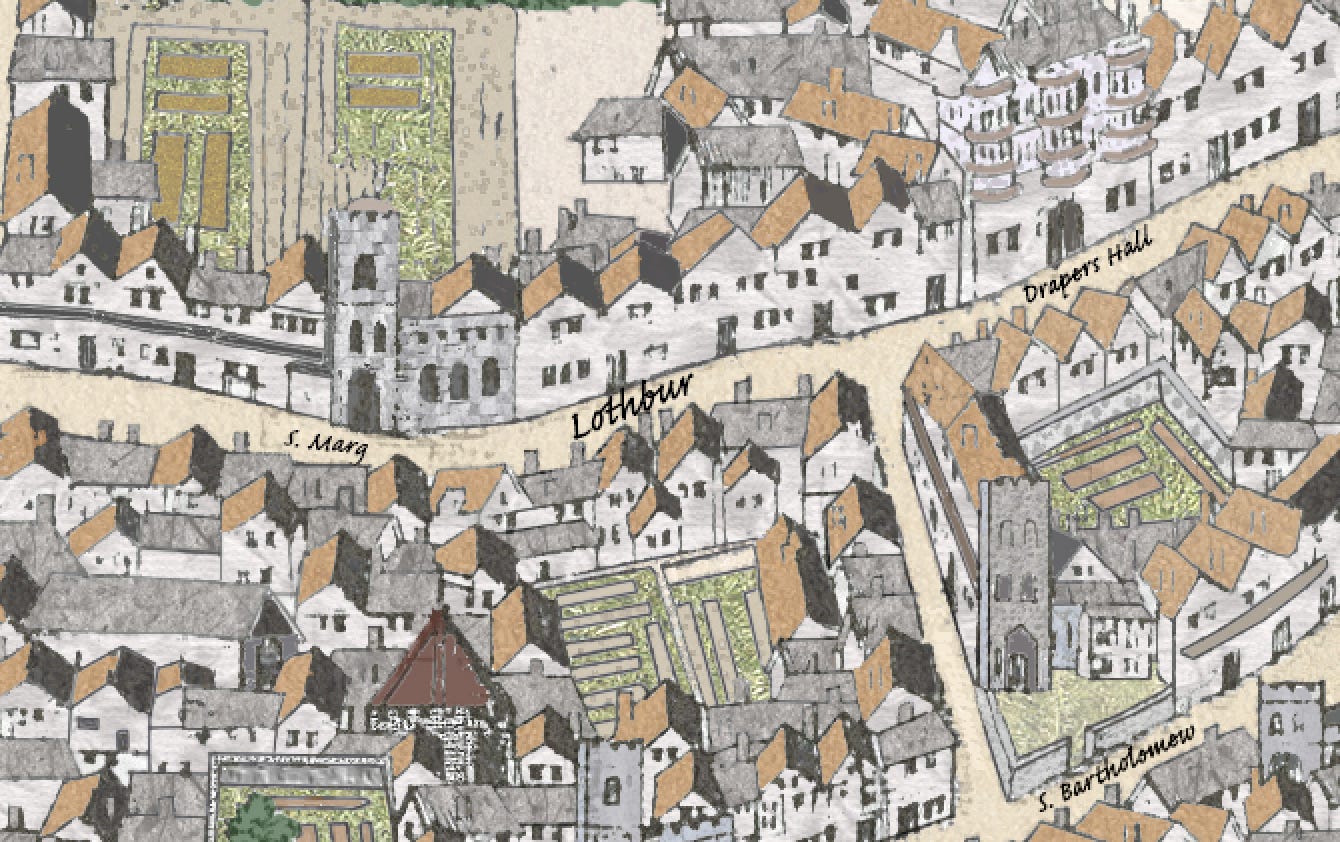

I mean, just look at the state of Lothbury:

Here’s how it looks after I’ve had my digital crayons out. It’s still one of the ropier bits of the map, but is now much easier to understand, I think:

Because the original is so deteriorated, what you’re looking at now is not only a colourised version, but also the clearest version that anyone has seen for centuries.

That said, it’s important to note that my additions of colour and texture are not necessarily historically accurate. For example, I’ve no idea what people were growing in those many individual gardens and fields, so I simply used generic grass and turf colours, with occasional flowerbeds for variety. Also, and to aid clarity, I’ve stuck fast to the same formula when colouring buildings. West-facing roofs are always orange-brown, for example, and most building walls (that are not in shade) are given the same off-white colour you might expect on a medieval half-timber building. In reality, there would have been more variety.

The original map contains about 90 labels, which include streets, churches, wharfs and civic buildings. How the original artist chose what to label is something of a mystery. Only perhaps half the churches are labelled, for example. Narrow alleys sometimes carry names while some major routes do not. About three-quarters of these labels are faded to the point where they are impossible to read accurately. In such cases, I’ve used the slightly later ‘Agas’ map (which is based on the Copperplate, though in lower detail) to have a guess at what the label might have originally said. Again, please take label spellings as my personal interpretation rather than historical fact.

What can we see in the colourised map?

The most obvious thing that jumps out the density. Thousands of individual buildings are shown. Most of them are generic houses and business premises drawn to the same shape. But the map also contains a hundred or more structures that have an individual identity.

The Ledden Hall, for example, is shown as a quadrilateral castellated structure, a million miles from the Victorian eye-candy of Leadenhall Market so beloved of Instagrammers today. London Bridge stands upon its paddle-shaped ‘starlings’ as it disappears off the bottom of the map. And dozens of churches rise above the streets; many remain (though almost all rebuilt) today. As we’ll see in a follow-on article, these seem to have been drawn with diligence. They are not simply ‘generic’ church shapes, but match up with reality.

One old building is conspicuous by its absence. The Royal Exchange would soon dominate the triangle of land at the western end of Cornhill. But we’re too early. It wouldn’t rise for another 10 or 15 years. Actually, that whole junction looks rather alien. We’re used to seeing the Bank of England, Royal Exchange and Mansion House standing here, but instead we find fingers of small buildings converging on what I presume is a water pump. The unlabelled centre-most church (of the five in this small section!) is St Mary Woolnoth, whose Hawksmoor-designed successor can still be found at the junction.

The street names will be mostly familiar, if spelled a little differently. Wall Brooke, Old Juree, Lombards Streete, Canon Streete… the campaign starts here to revive the spelling of Puddinge Lane. It’s remarkable just how much of the Copperplate street plan still exists, despite a Great Fire, the Blitz and five centuries of redevelopment. Some roads will not be found on your GPS, however. Blanch Appleton and Tournebasse Lane are two such long-lost streets.

Finally, the map contains a handful of human figures along the Thames. Most were badly degraded and a challenge to colour in, but I’ve done my best. I’ve also taken the opportunity to add myself into the map (Where’s Wally-style). Look for the man in the blue beany hat, far away from the river.

As with the second plate, I’m going to publish a complete gazetteer of all 90 places labelled on this panel. It’s an absolute whopper, with plenty more detail (and a few surprises). That’ll be in Friday’s email — which normally goes out only to paying subscribers, but this week I’ll also send out a slimmed down version to non-paying subscribers. If you’d like to see the full thing, it’s just £5 a month (which gets you many additional articles and invitations to meetups and events, full archive access, as well as the warm fuzzy feeling that you’re helping to support the quite hefty work that goes into this advertising-free newsletter).

What next?

It’s been immense fun spending so many hours with the Copperplate map, colouring in the three panels and spotting many details that had previously eluded me. My absolute dream is that somebody, somewhere will chance across further panels so we can see how the map expands outwards. If you have a 16th/17th century Flemish painting in your attic, check the reverse!

Either way, you’ll be seeing plenty more historic mapping on Londonist: Time Machine. I’m currently working on mapping everything in John Stow’s 1598 Survey of London, for example (that’ll take me till summer!), and I’m half tempted to start colouring in the John Rocque maps from the mid-18th century, though that would be even more ambitious. Suggestions always welcome.

Feel free to leave a comment below, or contact me on matt@londonist.com (I’m also on Substack DMs via

).Next week: I’ll have another “Past Futures” newsletter for you, looking at how Londoners of yore imagined the city of the future. This time round… did the Victorians foresee the coming of the car and the demise of the horse?

Great stuff Matt and thank you. I've got Cross's New Plan of London 1835 on my wall but that would be a huge endeavour!!

Thank you. V interesting