Welcome to Londonist: Time Machine, an ever-so-slightly geeky newsletter about London history.

A lonesome bollard stands on a lawn. What is it for? What does it protect? By whom was it installed? What the heck were they smoking?

Bollards usually stand by the roadside. They prevent vehicles from mounting kerbs. This one is a scrimshanker. It is entirely surrounded by grass. You could skid doughnuts around it in a double-decker bus. It is an impotent bollard. The curious post is just one of the many peculiarities in Regent Square.

Bloomsbury is famous for its Squares. You’ve heard of Russell Square, Bedford Square, Queen Square and others, but perhaps not Regent Square. Bloomsbury contains 13 named squares but this, I would tender, is the least recognised and least visited.

Yet its two or three acres are peppered with unusual features, and its history throbs with interest — much of it macabre or bleak. Indeed, Regent Square’s past is so busy that it could furnish several newsletters. You must forgive, then, the breathless pace at with which the following unfolds…

When this was all fields…

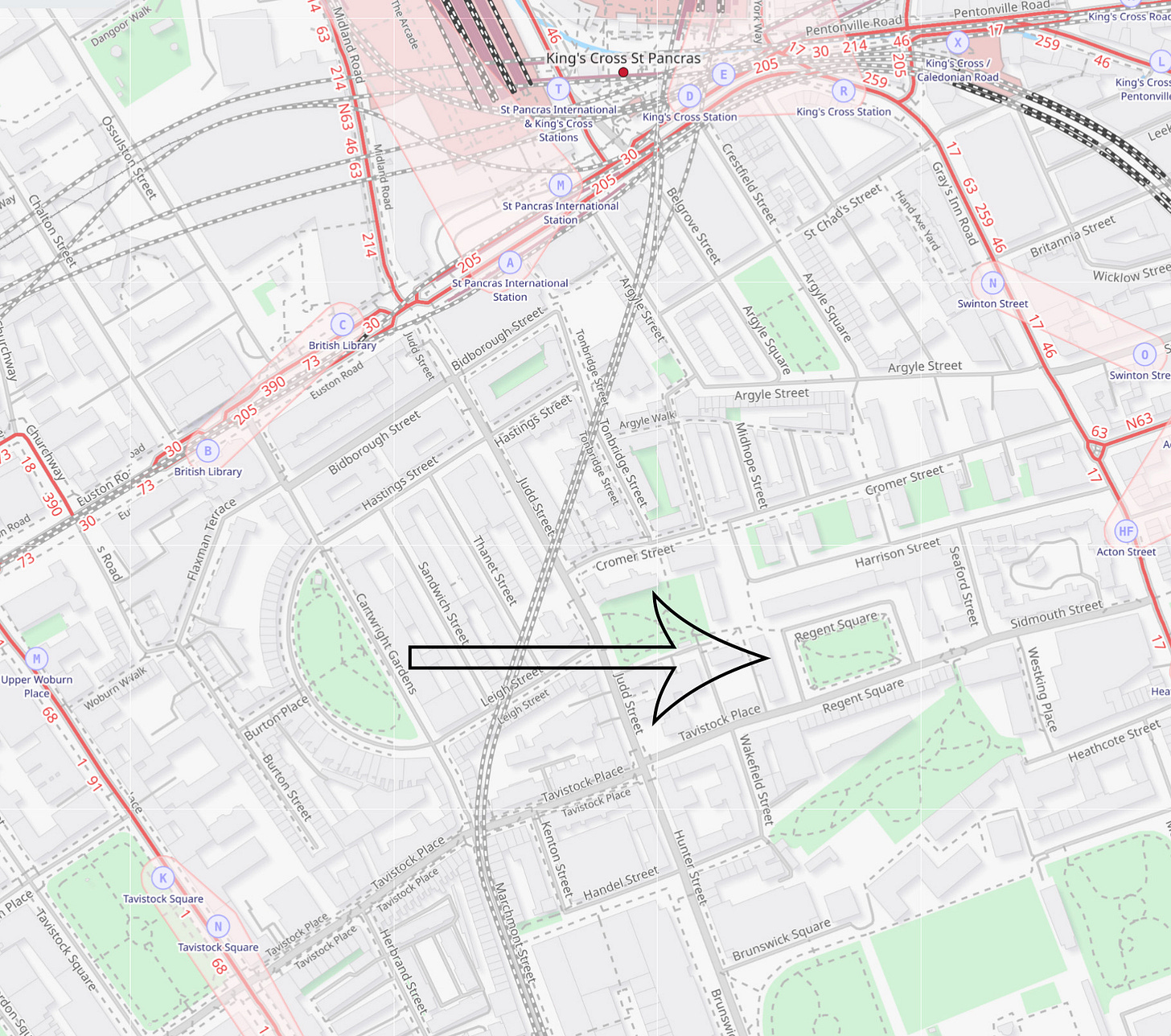

I better start by showing you where Regent Square actually is. Many readers will have found the square before, but the majority will be hearing about it for the first time, I suspect. To get your bearings, we’re in north-east Bloomsbury, a short stroll south of King’s Cross/St Pancras:

Regent Square has been with us for almost 200 years. It was laid out in the late 1820s and early 1830s on fields belonging to Thomas Harrison — a name still remembered in nearby Harrison Street and the fine Harrison pub. The square was named, like Regent Street, Regent’s Park and the Regent’s Canal, after the Prince Regent1, even though he’d graduated into George IV several years before any development began in the square.

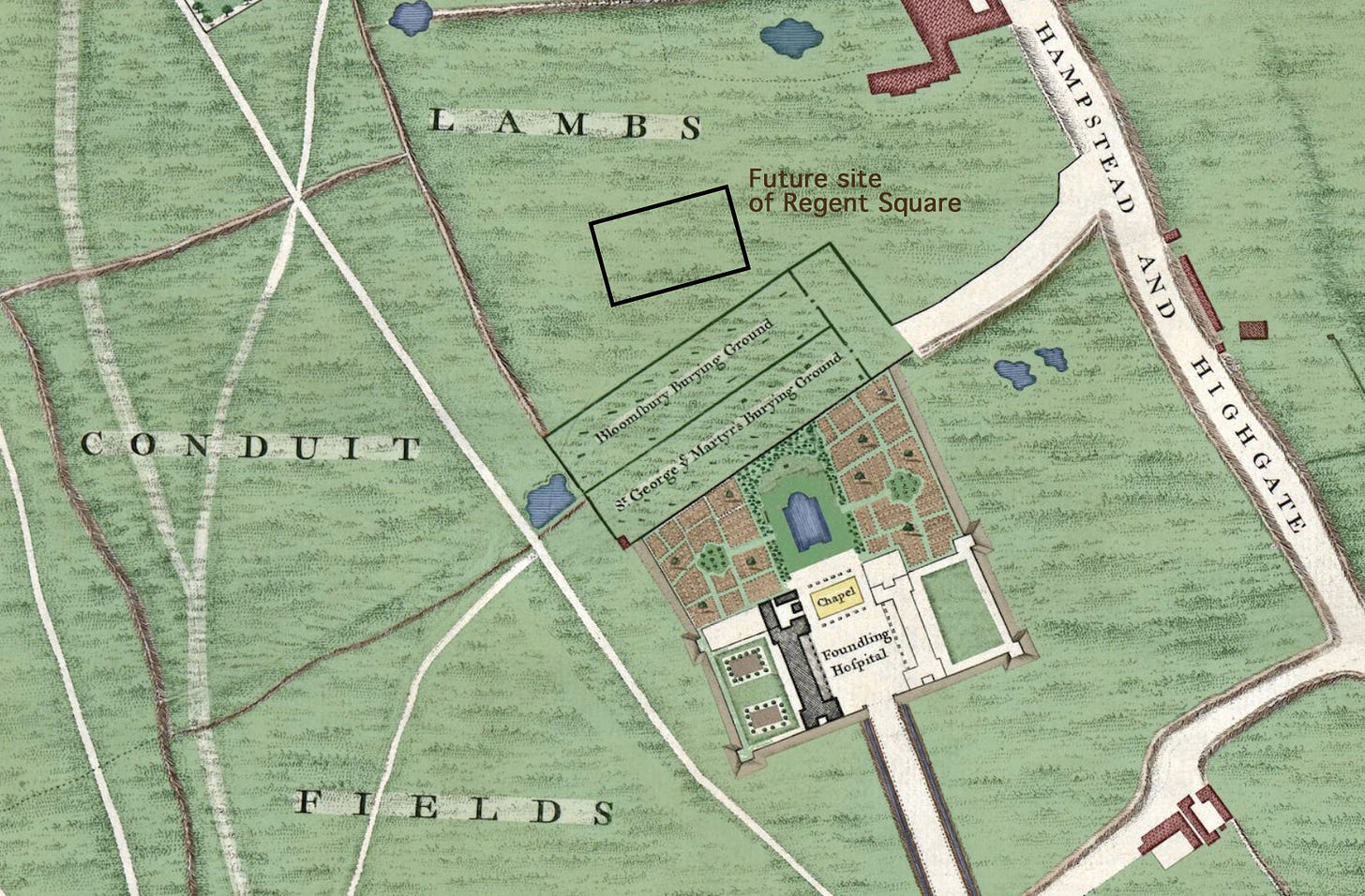

Let’s briefly wind back a century further and look at the area in the 1740s. Had you visited then, you might have bumped into John Rocque’s surveying team, swinging their measuring rods around. Here’s what they recorded (with added colour):

As you can see, the area was largely open fields — Lamb’s Conduit Fields — used for pasture and brick making. The biggest landmark hereabouts was the Foundling Hospital, and a curious bipartite burial ground immediately to the south. We’ll dip into that later.

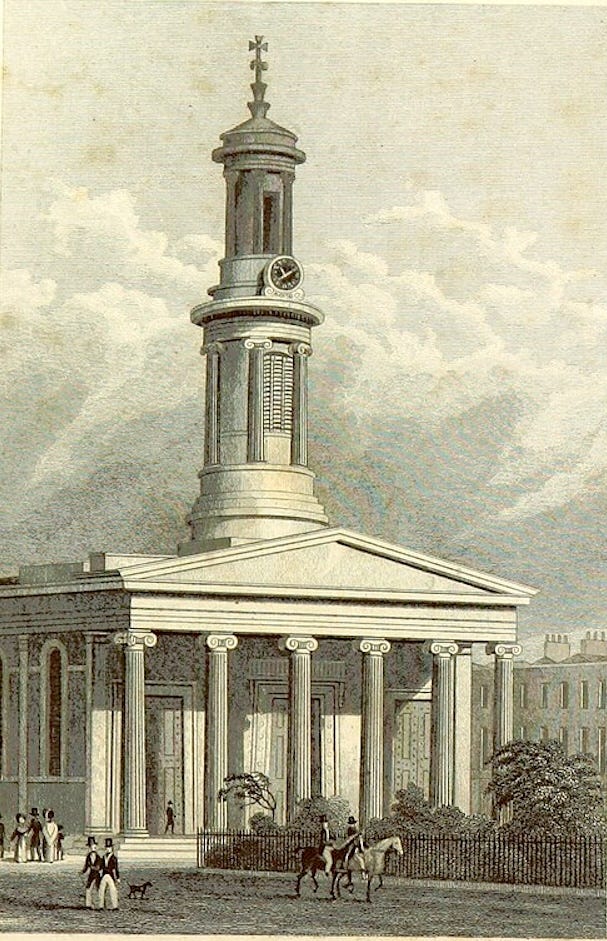

By 1830, those fields had all-but-vanished. Regent Square and its surroundings were the last corner of Bloomsbury to be developed. Unusually, this late square came with two substantial churches. St Peter’s on the eastern side was a dead-ringer for St Pancras New Church, which still stands opposite Euston Station (they had the same architects). Meanwhile, the ‘Caledonian Kirk’ in the south-western corner was a more gothic affair riffing improbably off York Minster. It catered for Scottish Presbyterians. Both churches were built before the housing, and both would meet untimely ends, which we’ll come to in two shakes of a lamb’s tail.

The new square was never as well-to-do as its predecessors to the south-west. The Booth poverty map of the late 19th century classifies it as “Fairly comfortable or Middle Class”, but with pockets of poverty all around. While never squalid, this was still a place where ‘things could happen’. And happen they did…

Murders most horrid

“Fiendish Crime in London,” ran the Standard’s headline. “Mutilated Body of Woman Under Sack”. The news broke on 2 November 1917. Early that morning, a local resident on his way to work had noticed a pair of suspicious sacks, just within the railings near the south-west corner of Regent Square. On opening the larger sack, he was horrified to discover the torso of a woman. Somehow, he mustered the courage to open the second sack, and there he found parts of her legs. The hands and head were missing.

The body had been terribly mutilated, presumably to slow down identification. Nevertheless, the police worked quickly. Within days, French national Emelienne Gerard was identified as the victim. Clues on the body led back to Frenchman Louis Voisin of 101 Charlotte Street. The two had been romantically involved. During a Zeppelin air-raid, Gerard had rushed over to Voisin’s home for shelter, but there found him with another woman, Berthe Roche. An argument ensued in which Gerard was battered to death. Voisin — a butcher by trade — then cut up the body and dumped it in Regent Square, half a mile from Charlotte Street.

The butcher’s guilt was quickly established when Gerard’s head and hands were recovered from Charlotte Street. Voisin was sentenced (in French, apparently) to be hanged, and was executed in Pentonville prison a few months later. Berthe Roche was also found to be an accessory to murder, and was given a seven-year sentence. Those who enjoy the twists and turns of true-crime stories can read much more about the case online or via podcasts. I must confess, I don’t really enjoy writing about them.

It was one of the most grisly murder cases the capital had seen in years, but this was not the first tragedy to befall Regent Square. 24 years earlier, in 1893, a double murder occurred on the roadway of the north-east corner. Electrician Leo Percy, in a premeditated act borne of jealousy, fired a revolver at his former girlfriend Daisy Montague and her new beau Samuel Garcia, before turning the gun on himself. All three died. This case has received much less attention online. One of the very few detailed accounts can be found here.

Appalling though these murders were, tragedy on a greater scale awaited the square, and in a form unimaginable in 1893, or even 1917.

Death from above

Late afternoon, 9 February 1945. A V-2 rocket accelerates from its launchpad in the Hague, a town still occupied by Nazi forces. Within minutes it has left the atmosphere and entered space. Its single engine cuts off. The projectile continues on a ballistic path, reaching apogee and then arcing down, down towards London. Just five minutes after it left the Hague, the rocket smashes into a church hall to the south-west of Regent Square. 34 people are killed in the explosion, and 121 injured [ref].

That death toll is high, even for the lethal V-2. Only three other rocket attacks on London would claim more lives in 1945 — those at Smithfield, Deptford and Hughes Mansions in Whitechapel. All of those strikes are well-known, but the Regent Square attack, despite its central location, remains obscure.

As well as claiming so many lives, the rocket strike also wrecked the old Presbyterian church in Regent Square. The roof and windows were totally blown out, and the wider structure was so damaged it was considered beyond repair. It was eventually torn down, and in its stead arouse what is now the Lumen church. This is a much more modest building from the outside, but boasts a unique and striking interior, worth seeing if you find the door open. Meanwhile, the church house that had taken the brunt of the strike was rebuilt, and a memorial plaque commemorates the 10 people killed inside.

As maps show, every building in Regent Square was damaged to some degree in the war. This included the second church, on the eastern side. St Peter’s was hit on several occasions and lay shattered for many years after the war. As the information board in the square notes, the husk stood “with its columned portico and pillared tower resembling the Grecian ruins its architects had originally been inspired by”. It was eventually pulled down and replaced with housing, known as St Peter’s Court.

Back to the bollard

With all the tragedy the square has endured, you might think that the mysterious post in the centre of the garden is some kind of memorial — a silent, onyx sentinel in remembrance of a bleak past. Not a bit of it. Our bathetic bollard is actually a work of location-specific art. It was installed in 1999 as part of a community artwork by Judith Dean, along with five similarly pointless bollards in the surrounding streets.

I won’t tell you where they are. Next time you’re in the area, I encourage you to go bollard spotting. All six are the same size and shape, and all are positioned with gleeful futility. It’s conceptual art at its finest; an installation that hardly anybody notices, but once you do, you have a kind of ‘secret knowledge’ about the local area. It makes you wonder what else might be hiding in plain sight.

The black posts are not the only concealed oddities in the area. If you look up into the boughs of the mighty plane tree at the centre of the square, you might notice a collection of exotic sculptural birds. These, too, have been hanging around since the late 1990s, the work of artist Johanna van Benthem and a group of local young people. The birds have since been eclipsed by a very noisy flock of real parakeets — rare in the late 90s, but now common as sparrows — who dominate the square as dusk sets in.

Meanwhile, if you walk through the south side of the square, then you’ll surely notice a prominent ‘ghost sign’ painted onto the end of the 19th century terrace. This is a relic of Bates & Co., a chemist that formerly traded from this spot. The sign is much faded and overwritten, but we can clearly make out the words “Cures wounds & sores” at the bottom. Personal injury is quite literally written into the history of the square.

Death and the maiden

At the south-eastern corner of Regent Square, a narrow passage leads through to a burial ground. We saw this on the John Rocque map above. Back in Rocque’s time, the ground was divided in twain by a wall. Now we see only stepping stones. Those who died in the parish of St George’s Bloomsbury were buried in the northern half (right of the stones in my photo), while those from the parish of St George-the-Martyr (Queen Square) lie to the south (left). For any novelists reading, there’s definitely scope here for a Bloomsbury version of Lincoln in the Bardo, with rival spirits unable to cross between the two necropoli.

Neither churchyard has seen a burial for 150 years. The two grounds were converted into a public garden in the 1880s, but this remains consecrated ground. It is a peaceful place around which to wander, and of quite different character to other gardens in Bloomsbury. Here you might stumble across the grave of Anna Gibson, favourite grand-daughter of Oliver Cromwell. Or perhaps you’ll find the discarded briefcase full of screws and plumbing parts, which I trepidatiously examined near the southern wall. Most likely, you’ll meet this lady:

This is Euterpe, muse of music and lyric poetry. As you can see, somebody has augmented her head with battery-powered Christmas lights and baubles. Euterpe once stood with her eight terracotta sisters on the side of the Apollo Inn in Tottenham Court Road. This was demolished in the 1960s to make way for an extension to Heal’s furniture store. The demi-goddess was gifted to the people of St Pancras, while architectural critic Nicholas Pevsner bagged Clio, muse of history, for his garden. What became of the other seven is a mystery.

We’re almost done now, but there is one more unusual feature just around the corner that should be pointed out. The western end of St George’s Gardens leads out to Wakefield Street, which runs back up to Regent Square. Here, you’ll find one of London’s more unusual plaque dedications:

“Stella and Fanny”, as the plaque attests, were noted cross-dressers at a time when such pursuits were considered suspicious or even "an offence against public morals and common decency". In 1870 the pair were arrested and charged with the “abominable crime of buggery”, on only the most circumstantial of evidence. They were subjected to humiliating physical examination without consent, and traduced throughout the press. They were later acquitted. The case was a landmark in British LGBT history and deserves an article in its own right. If you want to find out more, the National Archives has published an excellent account of the case and other documentation relating to their lives.

Regent Square, then, has a rich and often poignant history to rival any of the better-known Bloomsbury squares. At the same time, it has more than its fair share of physical oddities to puzzle the mind. It deserves to be better known. Do swing by next time you have an hour to kill near King’s Cross. — and remember to look out for those rogue bollards!

Thanks for reading! As ever, please do leave a comment below, or email me any time on matt@londonist.com.

Thank you especially to all those readers who have taken out a paying subscription. These newsletters could not exist without your kind support.

Bonus local fact. Nearby King’s Cross also gets its name, indirectly, from this regent/monarch. A large memorial to George was built near the current station, known as the King’s Cross. It only lasted a few years, but became such a noted landmark that the wider area, and later station, took their names from it.

It's of no interest for anybody but me, but I spotted a London taxi parked up in Regent Square with the plate number 12345. (The plate records that the vehicle has been inspected and certified fit for use to ply for hire.)

Mecklenburgh Square near Coram's Fields is well worth a look. When I worked around the area delivering parcels I'd stop off for a break there, watch the sheep trimming thd grass around Coram's Fields.