The Remarkable (and Grim) History of Southwark Bridge

It took 50 lives to build it... and then it exploded.

Happy New Year everyone! 🎇🎆

I’ve long felt sorry for Southwark Bridge. Who ever talks about it? This is central London’s least used bridge, and always has been. It’s the span with no fan; the underclass overpass. It is a bridge of meagre renown. But that’s not really fair. Southwark Bridge is a characterful crossing, imbued with unique shapes and colours. It has also a history to compete with any of its neighbours, albeit a tragic one. Our first newsletter of the year, then, is the little-known history of the little-appreciated Southwark Bridge.

That’s for the main feature. But first, I want to start off with a quick note about where Londonist: Time Machine might be heading in 2024. You’ll see plenty more maps, that’s for sure. I’ve got another instalment of the colourised Copperplate on the way, as well as a new map showing every street and building visited by Sherlock Holmes. I’m also planning a celebration of Peter Ackroyd’s London The Biography, the book that got me (and thousands of others) hooked on London history almost quarter of a century ago. And, yes, there will be a map.

We’ve also got a few site visits in the works for paying subscribers (see button below for how to join the club), as well as a general drinks meet-up in the very near future. And I have dozens and dozens of ideas for additional articles. So many, in fact, that I’ll need a real time machine to write them all up. That doesn’t mean I’m not looking for fresh lines of enquiry. So, if you’ve got a topic you’d like me to explore, then do drop me a line (email at bottom of newsletter).

Anyhow, here’s to an excellent 2024 for us all — and I look forward to meeting a few more of you at upcoming events. Cheers, Matt.

The Remarkable (and Grim) History of Southwark Bridge

“BOOM!” The south-west corner of the bridge exploded. Gravel, shattered flagstones, and flash-baked dung rained down onto its compromised deck. A chain of fireballs raced along the opposite side of the bridge, while ruined masonry plunged into the Thames. Witnesses would have likened it to a scene from a Hollywood blockbuster, if only Hollywood had existed.

Five people were injured in the Southwark Bridge explosion of 1 February 1895. The cause was traced to a gas leak. Snow and frost had sealed up the gaps between flagstones, preventing the gas from seeping out. One spark later, and half the deck was in the air. Luckily, nobody was killed on that occasion. But it wasn’t the first accident on this most troubled of bridges. Nor would it be the last…

From Wonder to Blunder

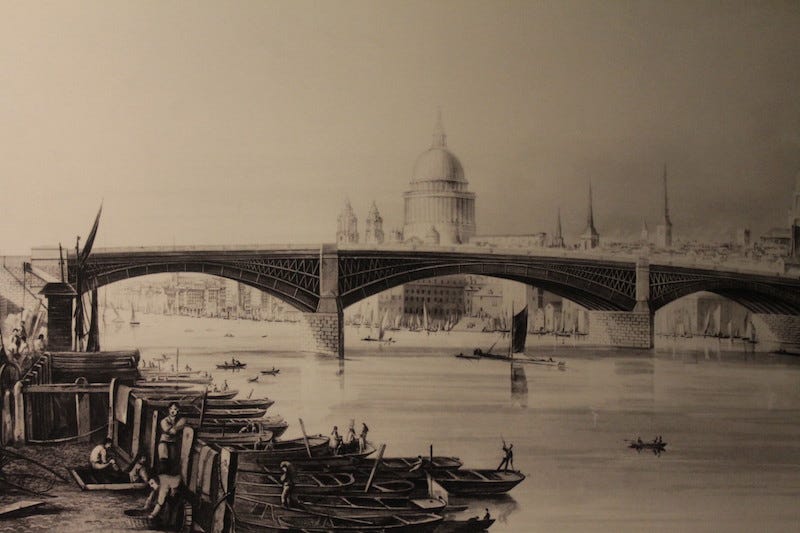

What we see today (top image) is the second Southwark Bridge. The first opened in 1819 to relieve pressure on the nearby Blackfriars and London Bridges. Unlike its sister spans which were owned by the City of London, the new crossing was privately built by the Southwark Bridge Company. Their big dream was not to aid cross-river traffic, but to make wads of cash through tolls.

It was an awesome structure, mind. Built with huge quantities of iron from the foundries of Rotherham, Southwark Bridge boasted a 73-metre span -- a world record that has never been surpassed in cast-iron. Press reports of the time describe it as “a stupendous structure... charming, graceful and fairylike”. “It is a curious fact,” noted one trivialist of the time, “that the centre arch is 38 feet (11.6 m) more in the span than the Monument is in altitude from its base to its gallery”. Southwark Bridge was dubbed a modern Wonder of the World. It had to be unveiled at midnight to keep the crowds to manageable numbers.

But the “stupendous structure” was also a stupendous failure from the very beginning. At least 47 people lost their lives during its construction, an unthinkable tragedy today, and grim even by the standards of the time. In one particularly appalling incident, 13 workmen were drowned when an overloaded transport boat capsized. The “fairylike” bridge was nothing of the sort.

It was also a financial flop. Cost over-runs meant that the architect, John Rennie1, had to sue the Southwark Bridge Company for his fee. The company had hoped to recoup its outlay by charging a penny per crossing, but this proved optimistic. The nearby Blackfriars and London Bridges could be crossed without any charge, and they also presented shallower gradients — an important consideration in the age of horse-drawn freight. This absence of traffic even made it into literature. Dickens placed a scene between Little Dorrit and Arthur Clennam on the span : “Thus they emerged upon the Iron Bridge, which was as quiet after the roaring streets as though it had been open country.”

The toll was finally removed in the 1860s after the City of London took on ownership. This brought in more traffic, although the bridge’s “hump” still put off larger vehicles. It remained central London’s quietest bridge for many decades (other than, you know, that huge gas explosion in 1895).

A traffic survey in 1912 showed just how neglected it was:

London Bridge: 125,370 (vehicles per week)

Blackfriars Bridge: 112,305

Tower Bridge: 85,353

Southwark Bridge: 24,432

London Bridge received five times as much traffic, despite being only 450 metres downstream. Southwark Bridge had had almost 100 years to bed in by this point, but it was still under-performing.

The City of London decided to smash it all up and start again with a new bridge designed by Sir Ernest George and Basil Mott. Their plans called for five spans instead of three. This allowed for a shallower gradient, while bringing its apertures into harmony with the five arches of neighbouring bridges. It would also be built from steel rather than iron, to provide strength and durability. Meanwhile, the approach roads would be remodelled to tempt more traffic.

Construction began in 1913, but was soon slowed down by the first world war. With labour and material shortages to overcome, it would take almost a decade to complete. When the demolition crews got to work on the original piers, they found a message on the foundation stone commemorating the Napoleonic Wars: “The work was commenced at the glorious termination of the longest and most expensive war in which the nation has ever been engaged,” it read. By chance, this new span was erected during an even bigger, even more expensive military crisis.

The bridge was finally completed in 1921. Its construction costs, swollen by shortages during the war, were met “without burden upon public funds,” as a sign on the bridge reminds us to this day. The cost was met by the Bridge House Estates — a medieval charity whose accumulated wealth still funds repairs to City bridges today (under the name of the City Bridge Foundation).

The new Southwark Bridge solved many of the problems with its predecessor, but it, too, has seen enormous tragedy. In the early hours of 20 August 1989, very close to the bridge, the pleasure boat Marchioness was struck by a larger vessel. It sank with the loss of 51 lives. This was, and remains, the worst maritime disaster in central London’s recorded history. By chance, the tragedy unfolded a little after 1.30am, the same time as the fatal capsizing that had killed 13 bridge workers 170 years before.

The great steel serpent

The replacement bridge is itself now over a century old, and Grade II-listed. It sees far more traffic than its predecessor. Yet it remains a curiously muted crossing. This is partly due to the south London road network, which filters traffic more naturally towards London and Blackfriars bridges. (There’s also a ‘no right turn’ onto Southwark Bridge from Thames Street.) The crossing has, however, become very attractive to cyclists. Almost half the carriageway is now given to segregated cycle superhighway 7.

It’s a bridge with eccentricities, for sure. Take the colour scheme. The chief hue lies somewhere between green and turquoise, paired with a dirty amber. It’s as though one of London’s famous ‘pea-souper’ smogs had condensed around the cold metal. The saurian shades give the bridge serpentine appearance, like one of the City’s heraldic dragons has stretched out over the brine.

The bridge’s adornments are also unusual. I can never resist peeking out of those granite-rimmed portholes or smiling in admiration at the trident-shaped lamps (not the original ones, I’m told, but still rather lovely). The riverside underpasses at either end are also worth a look. The walls of the northern tunnel show bridge schematics and scenes from its history (though not the gas explosion). The southern tunnel has images of a Thames frost fair.

And then there’s the border question. We think of the City of London as being entirely north of the river but, in fact, a pair of pontine pili span the Thames into Southwark. These are Blackfriars Bridge and London Bridge.

Southwark Bridge does not do this. Only the northern half falls with City boundaries, while the southern stretch lies within Southwark. I’ve never understood why this is the case, and would welcome an answer in the comments if anybody knows. This mid-river boundary goes largely unnoticed, but does have occasional implications. For a brief time in 2014, the bridge moieties had separate speed limits (20mph and 30mph), reflecting the preferences of the City and Southwark, respectively.

Southwark Bridge, then, has many peculiarities, alongside a truly remarkable and tragic history. It deserves a bit more love from us all.

I want to leave you with one final, little known episode from the bridge’s beginnings. Had you been standing on the almost complete Southwark Bridge in July 1818, then you might have witnessed one of the most remarkable sights in the river’s history. A gentleman known as Usher the Clown set off from the bridge in “a machine like a washing tub”. The boat lacked oars or sail. Instead, it was pulled along by a team of four harnessed geese. The clown rode his anserine water-chariot all the way to Vauxhall.

It was a bizarre way to celebrate the city’s new crossing. But then again, Southwark Bridge has always been worth a gander.

Thanks for reading! I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments, or by emailing matt@londonist.com. Next week…the return of our Past Futures strand, looking at how Victorians and Edwardians imagined London’s future.

Just before he died in 1821, Rennie would also design the replacement of the medieval London Bridge. His son, also John Rennie, oversaw its construction. It is the Rennie version of London Bridge that was famously sold to a wealthy American in the 1968, and shipped off to Arizona (though it’s not true that he thought he was buying Tower Bridge). The talented Mr Rennie was also the architect of both Old Waterloo Bridge and Old Vauxhall Bridge. Oh, and most of the London docks.

Moiety and anserine are now added to my vocabulary, marvellous!!

When I lived in South East London in the 1980's, Southwark Bridge was always my bridge of choice. I actually felt quite sorry for it when they closed off access to Queen St on the north side. Feeling sorry for a bridge? That is sad! And of course cycle access still available which helps the popularity with cyclists noted by Matt.