Welcome to Londonist: Time Machine, the newsletter of London history.

People once moored boats here.

We’re looking at the York Watergate — not in York, but in London. The elaborately chiselled structure was once on the river, used by visitors to the London home of the Archbishop of York. The keen observer will notice that you can’t get a boat up here any more. Obstacles to navigation include 50 metres of lawn, a dual carriageway, an interceptor sewer, cycle superhighway C3, and the Circle-District underground line. It’s like finding a bus stop on the second floor of a shopping mall.

The York Watergate is a relic of another London. When it was built, some 400 years ago, the Thames lapped right up against its fancypants columns. Then, before you could say “vermicular rustication”, it found itself high and dry. Joseph Bazalgette’s mighty Embankment marooned the watergate far from the Thames. It lives on with no practical purpose, though it’s much treasured as an attractive bauble for Embankment Gardens.

Let us recall it to life, as a portal once again. The York Watergate can be our entry point into a London that is neither present, nor wholly lost. A London that was seemingly erased, yet lingers on in trace, remnant and shadow. It is our gateway to Vestigial London…

The not-so-lost rivers

Our watergate leads first to water. Vestigial London can be glimpsed almost anywhere, but is manifest most clearly in its waterways. The central city is built over five notable rivers, all now buried. These are the Walbrook, Fleet and Tyburn to the north; and the Effra and Neckinger to the south. All are now completely covered (apart from the mouth of the Neckinger), but each can be traced by close observation of surface features.

Let’s take the River Tyburn as an example. It rises on Hampstead Heath and flows down to the Thames at Westminster via the West End. Today, it does so in a sewer, but until the 19th century, much of it was above ground. The streets of Marylebone and Mayfair were built to accommodate its natural meanders. If we look at the satellite view of Marylebone, it leaps out like a salmon:

See it? Marylebone, unusually for London, is largely built on a grid system. But the ancient Marylebone Lane, which tracked along the banks of the River Tyburn, takes a more erratic route. I’ve highlighted it below in case it’s not obvious.

The missing river asserts itself in other ways. Next time you’re on Oxford Street, look at the slopes in the road. A very noticeable dip coincides with the junction of Wells Street. It’s the old river valley. You can see it also on Wigmore Street, the other west-east street a few blocks to the north. This is an obvious but often-overlooked tip for exploring London (or any city): if you find a place where the land slopes up in different directions, then you’re probably in an old river valley.

Let’s follow the Tyburn just a little farther, across Oxford Street and south into Mayfair. The telltale wiggle of the river continues here. If anything, it is even more apparent:

Most of the river was paved-over two or three centuries ago, yet this ancient feature has fossilised into tarmac, brick and Portland stone.

I won’t go into detail about how to follow this not-so-lost river. Several excellent books give full instructions and history of this and other rivers (I’d recommend Tom Bolton’s for the most thorough notes), or watch John Rogers’s personable videos. Suffice it to say, these telltale street patterns and still-extant valleys can be spotted with any of the ‘lost’ rivers. It is Vestigial London at its most ouvert.

The Romans still march through London

The satellite view above leads us on to other forms of remnant. See the flamboyantly arboreal road that runs up the left of the image? That’s Park Lane, the busy thoroughfare that separates Hyde Park from Mayfair. Today, it’s one of central London’s few multi-lane highways, and carries more traffic than any other street in that view. In medieval times this was a simple track, and probably formed the eastern boundary of the Manor of Hyde. Henry VIII built a wall along it, when he acquired Hyde in the 1530s and turned it into an enclosed deer-hunting park. This hard barrier reinforced the old boundary line, and further fixed the route of the lane. The wall vanished when the land was turned to park, but the road still follows its ancient route. Hence, a territorial boundary, defined a thousand or more years ago according to some forgotten agreement between bearded Anglo-Saxons, persists today as the thunderous barrier between Mayfair and Hyde Park. Such examples of ancient frontiers still intruding upon the modern street pattern can be found all over central London.

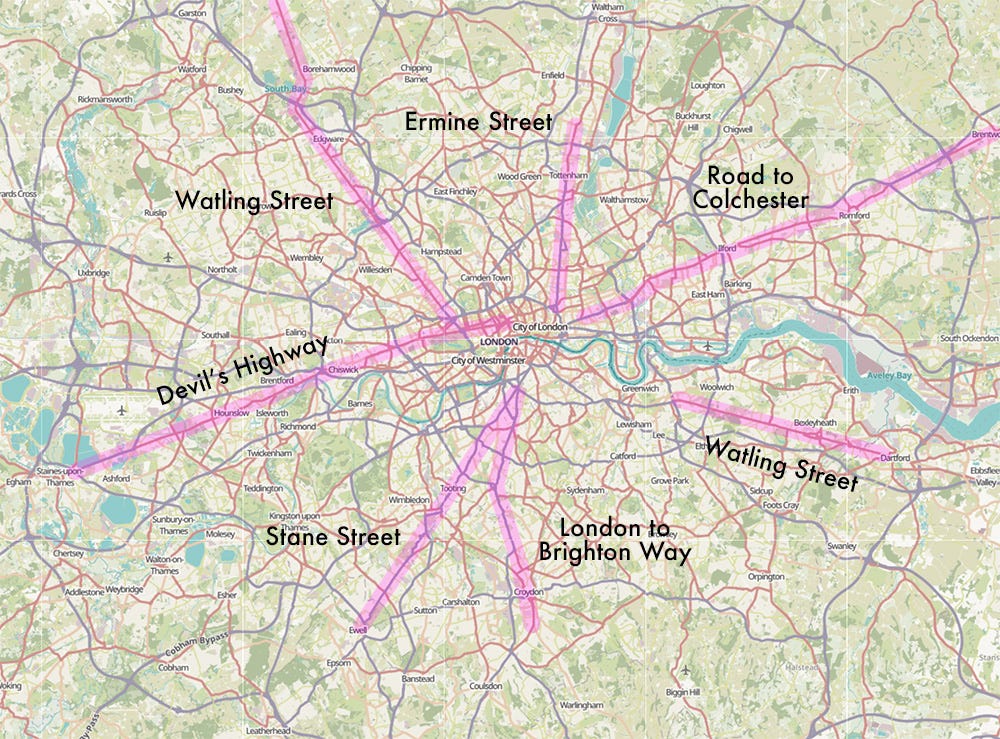

The satellite view above contains a second ancient road, in the shape of Oxford Street. It is Roman in origin, as are many of the main thoroughfares leading out of London. If we zoom out, and out, and out again, then these 2,000-year-old roads are clear straight-lines, heading out into the provinces. The Roman occupiers fled 1,600 years ago, but their local handiwork can still be seen from space.

At a more local level, these Roman roads contributed enormously to the development of London. They were originally laid down as a means of getting troops and trade between major Roman strongholds, and so follow the most direct paths as closely as possible. Their arrival points in London determined where the gates in the wall of Londinium (the Roman city) would be built. Hence, the positions of modern day Ludgate, Bishopsgate and Aldgate, among others, are the consequence of decisions made 2,000 years ago. Had a Roman surveyor rotated his groma a single degree to either way, then Bishopsgate would have entered the city at a different point in the wall, and my favourite sandwich shop would not exist.

We can perhaps go further. Parts of Watling Street and possibly Ermine Street followed ancient tracks that pre-date the Roman arrival. Some features of London may therefore trace their positioning and alignment to prehistory. We know precious little about the ancient Britons who walked these lands three millennia ago, but the number 53 bus would not be trundling along Old Kent Road if those feet, in ancient times, had beaten a different path.

The drovers’ trail

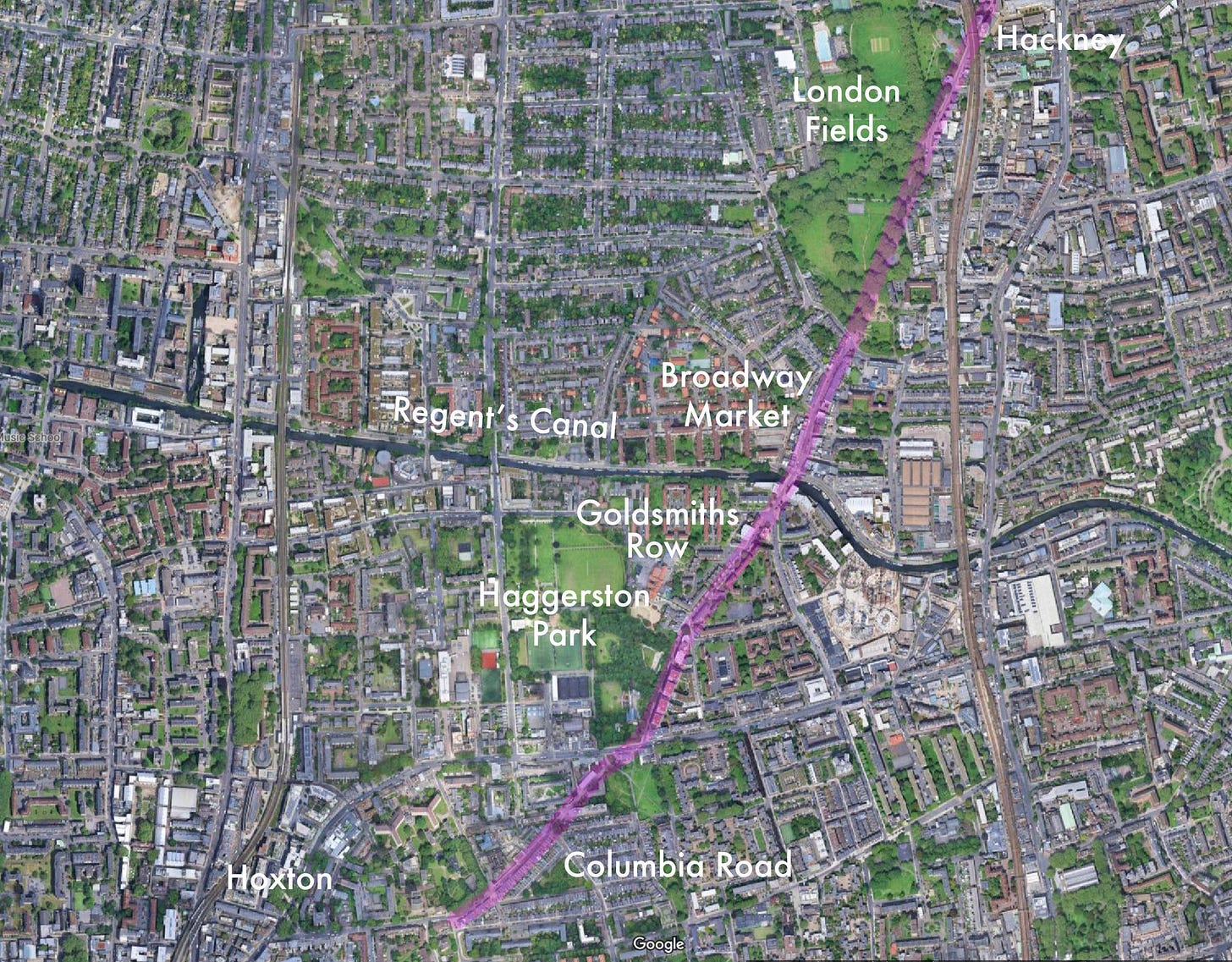

Not all ancient roads in London have Roman roots. A medieval drovers’ track, for example, can still be traced on the modern map of north-east London. Known, for reasons lost to history, as the ‘Black Path’, this route still cuts a convincing diagonal from Hoxton to Hackney Central (and thence Walthamstow, though that part of the route is less obvious on the street map). Here’s the satellite view:

This route would have been used by drovers to bring animals into Smithfield from Essex and beyond, on the long, sorry march to market. It was possibly taken in the opposite direction by pilgrims heading to a shrine in Norfolk. Today, it follows well-known but minor thoroughfares such as Columbia Road and Broadway Market — both, incidentally, centres of market trade since Victorian times. It is an atavistic nod to the much older drovers’ market track upon which they are located. I urge you to walk this route. It is lined with modern buildings, yet there is temporal magic in the steady, linear progress through minor backstreets and parkland edges. It is the ultimate desire line, written irrevocably into the fabric of London by centuries of use.

I find this route particularly fascinating, and I would have devoted a whole newsletter to it by now, had it not been so comprehensively and charmingly covered by the Gentle Author and John Rogers (again).

The lost bridge

London Bridge has been rebuilt many times. The 1970s structure we see today is a replacement for a 19th century bridge (the one that now stands in Arizona). Both these spans were built on a different alignment to the medieval and Roman bridges. These both straddled the river a little to the east of the current crossing. Happily, the mid-1820s Greenwood map of London was surveyed at exactly the moment that both old and new bridges were in simultaneous existence, so we can get a good look at the street patterns:

As you can see, the older (eastern) bridge is a better fit for the City of London’s street plan. It leads due north up Fish Street Hill and directly onto Gracechurch Street. The new bridge led straight into buildings, which had to be cleared to make way for King William Street. To the south of the river, meanwhile, Greenwood’s map shows how the course of Borough High Street has been diverted west to meet the new bridge; it previously followed that dotted diagonal to hit Tooley Street.

Here’s how things look today:

The old bridge is marked in red, with approach roads in amber. If you look to the north, it’s really obvious how a previously straight approach to the bridge had to be diverted west to meet the new crossing. The modern offices to the south of the old bridge have even preserved in their angles the old course of Borough High Street. This, I think, is deliberate. If you head to Tooley Street, the point where the yellow line becomes the red dotted line is marked with these parallel strips, heading out towards the river:

The brass strips are embossed with text, telling us that this is the old alignment of the bridge. A narrow gap has been left between the buildings, as if in reverence of the vanished structure. Then, if we back-track up to the start of the modern bridge, we find this grandiose stone needle:

It’s often claimed that this is a memorial to the old London Bridge’s spikes, upon which the heads of traitors were gruesomely displayed. The truth is more interesting. According to one account, the spike’s trajectory indicates the deleted course of Borough High Street, which led to the former bridgehead. Follow it backwards and you’ll reach the brass strips shown above, and thence the site of the old bridge. It’s such a wonderful, subtle marker of a vanished alignment — whether deliberate or accidental. I adore it.

We might, then, consider the London Bridge spike as the compass needle of Vestigial London. It is the fingerpost to a phantom crossing, a modern and much-ignored marker of things that were but are no more.

We could spin that needle and follow it to other places where old London still bleeds through the palimpsest. We might head to Red Lion Square, for example, where subtle alignments still hint at lost side-streets. We could return to Roupell Street, whose orientation perfectly matches earlier irrigation ditches seen in the John Rocque map. I’ve written before about how the shape of King’s Cross station was determined millennia ago by geological forces. We haven’t even talked about the history of place names, often the last echoes of vanished people, landmarks or trades.

Vestigial London is infinite, everywhere, and yet nowhere. It can only be accessed through a combination of observation and imagination. But once you step through the gateway or spin the needle, then you will never see the city in the same way again.

Thanks for reading this slightly esoteric instalment. Vestigial London bubbles up in so many more places than I’ve mentioned here. Please do share your own examples in the comments below. Or email me any time on matt@londonist.com

Anglo-Saxons didn't have to have beards to own property: women, married or single, could do so, without needing the consent of males in the family. To think it wasn't till 1975 that a woman could open a bank account without permission from her father or husband...

This was a joy! I knew about the Tyburn, but the detail about the old London Bridge was a surprise - I cycled via that narrow passage (St Olafs Stairs) to the river for several years, first going under the "new" London Bridge, and I had no idea I was using the old bridge route. So much buried historic treasure.