“I love walking in London,” said Mrs. Dalloway. “Really it’s better than walking in the country.”

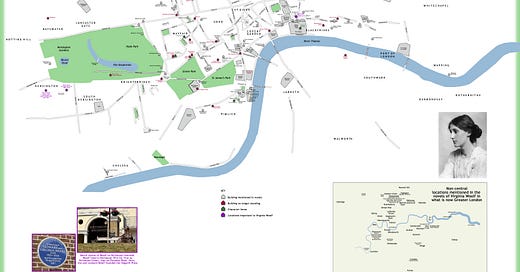

Having mapped Wolf Hall, I thought I’d turn to Woolf’s haul. That’s right, for today’s newsletter, I read all ten novels by Virginia Woolf, and mapped every London location she mentions.

Actually, that’s a bit of a fib. I did the reading a few years ago, when…