Welcome to Londonist: Time Machine. Today’s newsletter fixates on the Wolf Hall novels of Hilary Mantel. But don’t run away if you haven’t yet read them. I’ve put together the newsletter in a way that should still be thought-provoking for the Cromwell-curious. There may be a few spoilers, but as the trilogy deals with established history, then I think that’s fair game.

Like many, I find myself utterly transfixed by Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy. More than transfixed. I am in Henry VIII’s court. I have become Thomas Cromwell. I must skip a night’s sleep, then another, and keep on reading. It’s like her words are infused with nicotine.

No denying, though, that these books are complex. Mantel recounts the machinations of the Tudor court as skilfully as anyone who ever lived, but it is still a challenge to keep track of all the Marys, Henrys, Annes and Thomases, especially when they’re addressed by an ever-shifting range of titles.

I’ve always been an annotator. I keep lists of characters, make family trees, scribble in margins and — compulsively — draw maps. I can’t hold onto the information otherwise. This process of ‘extracting data’ from a novel is enjoyable in its own right. I find myself hoping that a new cousin will be introduced so I can augment a branch of the family tree, or that the characters will toddle off to Spain so I can sketch the peninsula onto my map. There’s always the possibility, too, that I might uncover something new that nobody has spotted before. Like mapping all of Dickens and discovering that he never once names a railway station.

I knew before I started reading Wolf Hall that it had to be mapped. This is an intensely London-heavy story. The super-protagonist Thomas Cromwell rarely leaves the capital, and it is through his eyes and thoughts that the tale unfolds. I wanted to map his London, and see which roads, buildings and areas Hilary Mantel pulls in. What I wasn’t prepared for was just how international things get. As we’ll see, the world of Thomas Cromwell stretches all across Europe and even to the opposite sides of the globe.

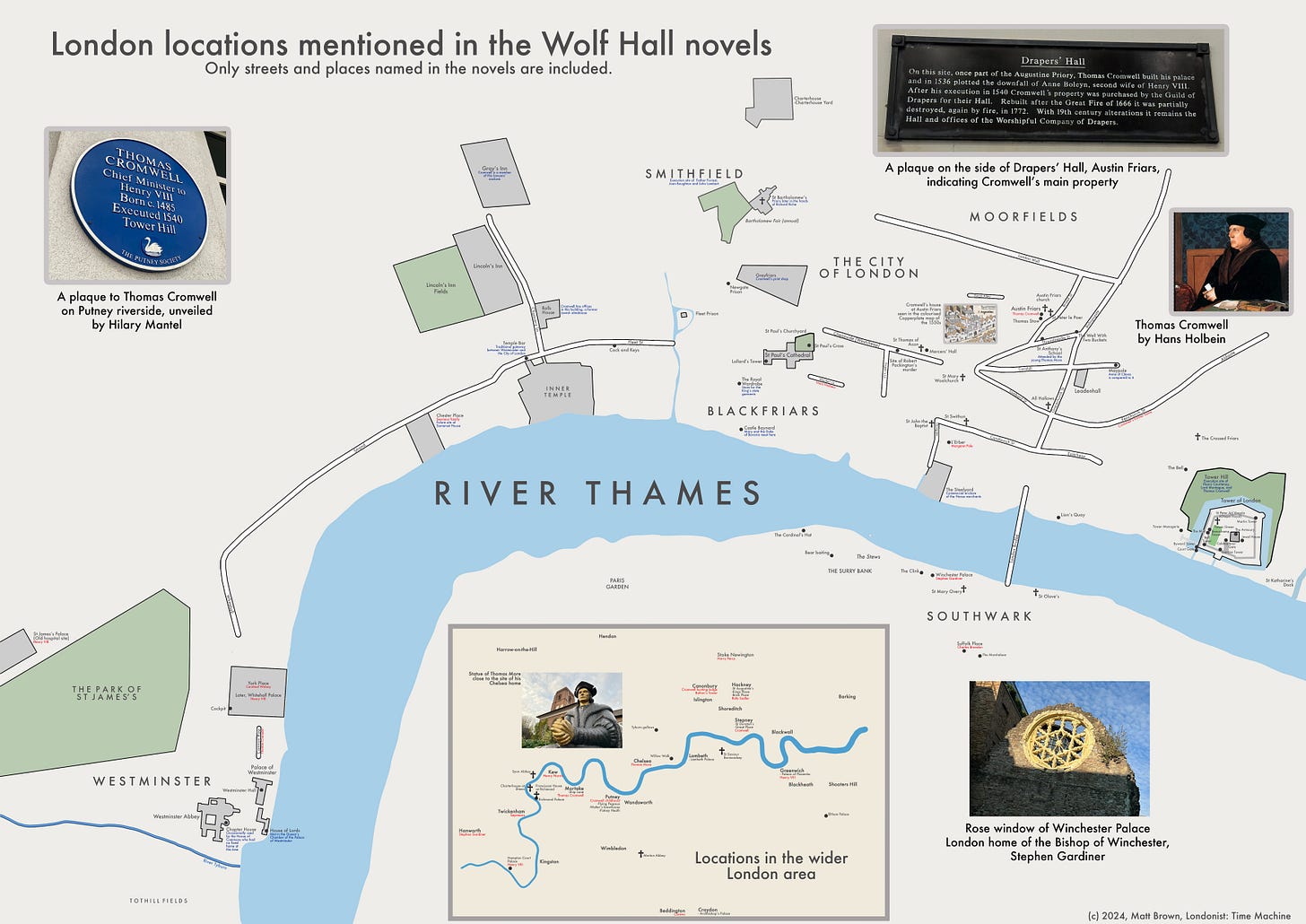

The geographic scope of Wolf Hall is such that I’ve had to divide the project into three maps — my own “three card trick”, if you will — which we’ll look at in turn. First is the London of Thomas Cromwell; then a map of the wider country; and then a third map showing locations across Europe, with an inset for the rest of the planet.

Before we get stuck in, I need to commend Simon Haisell’s Footnotes & Tangents substack. Throughout 2024, Simon ran a hugely insightful “Wolf Crawl”, a slow-read of the three novels that I only became aware of part way through my own reading. Simon will repeat the crawl with lots of new material (including maps) in 2025, so if you’ve yet to enjoy these astonishing novels, then now is your moment. Details on the 2025 Wolf Crawl here.

An important note on the maps

The three maps below plot only those locations that are mentioned in the text. If a place is not mentioned (such as Whitechapel or Ludgate Hill) it does not go on the map.

This is an indiosyncratic form of mapping, but it gives us a very focused appreciation of the places that are important to Thomas Cromwell (and/or Hilary Mantel), and the places that are not. The three maps together show every single mappable location mentioned in the novels, whether visited by characters or mentioned in passing. They are a geographic mirror to the novels’ light. Behold, the complete Wolf Hall geobibliome!

Let’s get stuck in!

The London of Thomas Cromwell

The Thames is everything. It flows through the novels like, well, a massive river. It would have been much wider in those days, before embankments. Thomas Cromwell is born and beheaded beside the Thames. Most of the royal palaces — including Hampton Court, Richmond, Westminster, Whitehall and Greenwich — nestle up to the Thames, as does the Tower of London. The great houses, too, including Thomas More’s pile in Chelsea, Cardinal Wolsey’s York House, Chester Place (London home of the Seymours), Winchester Palace (Stephen Gardiner’s HQ) and Margaret Pole’s house L’Erber, all lie within the sound of lapping water. Quite simply, the river was the most convenient and secure means of getting around, at least for those with money.

Consequently, the ‘interior’ of London is less well realised in the novels. Many of the major roads go unmentioned. Holborn is absent. Ludgate, Newgate and Aldersgate fail to register, though Bishopsgate and Aldgate do play a part. There is no West End. This part of town was still rural in the Tudor period, save for a ribbon development along the Strand (and a leper hospital at St Giles, not mentioned in the books, whose church is still called St Giles-in-the-Fields). The only grand house on the Strand mentioned in the novels is the Seymour family’s London home. This was called Chester Place until Edward Seymour, Jane’s brother, became Duke of Somerset in 1547… thereafter it was known as Somerset House, a name still famous today.

The busiest place on the map, though, is the central part of the Square Mile (City of London). These are the streets south of Austin Friars, the palatial home of Thomas Cromwell. Places like Cornhill, Lombard Street and Cheapside pop up time and again, though they rarely serve as primary locations. Most of the action in these novels takes place indoors, be it palace, posh house or prison cell.

Speaking of which, the best realised building in the novels is the Tower of London. Mantel is fastidious with its geography, noting 13 different named locations within its precincts. This is, of course, the scene of Anne Boleyn’s execution at the end of the second novel (and in real life). Various characters are grilled here by Cromwell and his lieutenants, throughout the novels. He, Cromwell, would himself spend his final days in the fortress, before having his head removed on nearby Tower Hill.

Much more could be said about Cromwell’s London, but I think I’ll save that for another newsletter. Let’s now cast our net across the wider country…

The Britain and Ireland of Thomas Cromwell

Unless I’m being forgetful, I think Cromwell only leaves the south-east a couple of times in the main narrative: once on a trip to Calais, and later on the king’s progression to the west, which ultimately leads him to Wolf Hall in Wiltshire. And yet look how many places are on the map — not just in the London region but up and down the land.

Most of the Historic Counties of England are mentioned by name, and all are represented by at least one town, abbey or stately home. We do see a few notable gaps. For example, no sign of Manchester, Birmingham or Liverpool. Clearly, locations thin out the farther we get from the capital. Contrast Devon or Northumberland with Essex or Surrey, for example.

Overall, though, I was quite surprised by the generous spread of locations across England. Much of this can be put down to imperilled abbeys. A good deal of conversation and correspondence is spent on which religious houses to close, and who might get the spoils. A quick scan of the map shows dozens of religious houses, marked by cross symbols, spread across the land.

Other consequences of the Dissolution are reflected in the map. The third book is particularly keen when it comes to the geography of the so-called Pilgrimage of Grace, a popular uprising in Midlands and the North against the break with Rome and the closure of the abbeys. Various nobles ride out to confront and suppress the rebellion. Cromwell, whom the rebels consider the bogeyman-in-chief, stays home, but follows developments closely through correspondence. Many of the map-points around the Trent and Ouse come from this episode.

In contrast to the coverage of England, the other future components of the UK are scarcely mentioned. Scotland in particular is terra incognito. We have to wait until the third book for any locations to get a look-in, and then it’s only a handful of places around Edinburgh and a shrine in Galloway. Wales and Ireland get a few more name-checks, but only in passing. (In retrospect, I could have chopped off most of Scotland and given more room to southern England, where the action is — but I’ll probably get enough grief for missing out the Shetlands.)

The wider world of Thomas Cromwell

And so to our third map, and perhaps the most intriguing. It’s tempting to think of Henry’s England as a parochial place, before the days of Empire and exploration. But, of course, the countries of Europe enjoyed a high degree of connectivity. For starters, the royal families and noble houses were all commingled in wedlock. Henry himself was married into Aragon and Castile through his first wife Catherine, and then briefly tied himself to German nobility through his marriage to Anne of Cleves. Meanwhile, pan-continental institutions like the Catholic church and the Holy Roman Empire ensured plenty of international intrigue. England itself could be considered to extend onto the continent, through its holdings in Calais, a town that plays a large, recurring part in the narrative.

As the top man of Cardinal Wolsey and later the King himself, Thomas Cromwell finds himself at the centre of this international web. He dines regularly with the Imperial ambassador Eustace Chapuys, negotiates with princes and lords across the continent and even finds that he has a daughter from across the Narrow Sea. Cromwell is himself a well-travelled man. In younger days he served in the French army, worked in an Italian banking house, strayed as far as Cyprus, and later became a cloth merchant in Antwerp (some of this biography is disputed in real life, but presented as fact in Wolf Hall). He speaks several languages. If Thomas More is the Man for All Seasons, then Cromwell is the Man for All Nations.

Though he rarely leaves the capital, Cromwell’s remote dealings and frequent flashbacks give us glimpses of many European towns and cities. France and the Low Countries are particularly replete with mentions. Italy, also plays a prominent role, both as the seat of the Pope, and as the playground for Cromwell’s early adventures. The still-wider world occasionally intrudes. The Turks are knocking rather loudly on the gates of Vienna. Cromwell is keen to “hear any news from Persia or the east, which the French always get before we do”. There is reference to China, the Indies and even Peru. In the moments before he is led to the scaffold, Cromwell wonders what will happen to William Hawkins’s expedition to Brazil. “I would have liked to know how that works out,” he muses. Mantel’s Cromwell was curious about the world to the final chop.

So much more could be said about the geography of the Wolf Hall novels. I invite you to leave your own observations in the comments below. In particular, there are a handful of locations in the text that I couldn’t identify:

The Queen’s Head Tavern, an unidentified pub mentioned in the first book, perhaps in Westminster.

The Mark and the Lion pub, a low tavern in which Harry Percy drinks.

Tilney Abbey: One of the threatened abbeys mentioned in Bring up the Bodies. I can find no real-life counterpart with this name, though a fictional building of similar title features in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. Is Mantel making a stupendously subtle pun by referring to Austen’s Friars?

Any information leading to the whereabouts of these three orphans would be gratefully appreciated. Finally, if you enjoyed today’s post, then you might like the other ‘geobibliomes’ in this occasional series.

A map of every London location mentioned in the novels of Charles Dickens

A map of every London location mentioned in the canon of Sherlock Holmes

A map of every location mentioned in Peter Ackroyd’s London: The Biography

And my books Atlas of Imagined Cities and Atlas of Imagined Places1, which explore fictional geography in much more detail.

Also, a thank you to the Historic Towns Trust, whose splendid map of Tudor London was very helpful in placing some of the features on the London map. A digital version is available through Layers of London.

Thanks for reading! Please do leave a comment below, or email me any time on matt@londonist.com. If you want to ask: “What about the TV series — did you like that? Why didn’t you mention it?” The answers are “yes, very much so” and “because I have too much to say about it, and don’t want to make the newsletter overly long. Another time”.

And a reminder that you can join in with the 2025 Wolf Crawl here.

Links go to Bookshop.org, which sources stock from independent bookshops and gives us a very small commission for any sales.

Oh Matt, making a connection between Jane Austen’s Henry Tilney and Hilary Mantel’s mention of Tilney Abbey is absolutely amazingly brilliant. Austen’s Friars! Professors in the US have gotten tenure for less! Thank you SO much for all the hard work that has gone into these posts. I LOVE them. I think our dearest Queen Hilary must be smiling at you too.

Oh wow! This is amazing! 👏👏👏