Welcome to Londonist: Time Machine. Today, I’m delighted to share another colourised panel from the John Rocque map of 1746. This time round, I’ve spent hours shading in the streets, squares, ponds, trees, fields, ditches and more fields of Georgian Bloomsbury. Because 250 years ago, London really did stop at Great Ormond Street.

The story so far… A quick primer for newbies to this newsletter

(You can skip this bit if you’ve seen the earlier panels.)

In 1746, John Rocque published the most detailed map of London ever created, up to that point. It is immense. Over 24 panels, Rocque and his crew mapped every street, square, farm, open space — even the alleyways — using professional surveying techniques.

The resulting map is one of the treasures of London. It is simultaneously a work of great beauty and great historical value. But such is the level of detail that it can be difficult to fully discern boundary changes, watercourses and patterns of land use. To that end — and as an excuse to spend many hours poring over this most spellbinding of maps — I’ve set out to colour-in every panel. My digital paintbrush has not only flicked over the buildings and grassy areas, but also the streams, churches, orchards, individual trees and even their shadows.

It takes ages, perhaps 30 hours per map. 30 joyous hours, I have to say, because the map is such a pleasure to explore. The end results, I hope, offer a fresh glimpse into the rapidly expanding Georgian city.

Today’s map is the sixth panel I’ve tackled. The previous five can be found below:

Southwark and the western City (plus the 50 lost waterways of Southwark)

London Bridge, Borough and the eastern City (plus the lost waterways of Borough)

Wapping and part of Bermondsey (plus lost roads of the East End)

Paid subscribers get full access to all these maps and the rest of the Time Machine archive.

A close look at the Bloomsbury map

The area covered by today’s map means a lot to me. I found myself shading in the section where I first met my future wife. Here, too, is the block where I got my first proper job, wrote my first article, got a picture of my gran on the front cover of an international science journal, and met so many lifelong friends. I look at those great open fields to the north of the map and think: “I bet I got rat-arsed in every single one of those, at some point in the Noughties”.

It’s Bloomsbury. We all have our memories and associations in this part of town. Only, this is not the neighbourhood we know today. The elegant squares, tourist hotels and highbrow literary associations are all for the future. This is a frontier land of farms, sodden earth and bounded fields. To the the far right, the River Fleet still meanders through its steep valley, a physical boundary between the parishes of St Pancras and Clerkenwell. It would remain uncovered in these parts well into the 19th century.

So much history could be unpacked in this mesmeric rectangle. I’m going to spread the load over two newsletters. In today’s, I’ll take a look at some of the highlights of the map. On Friday, I’m going to follow the water, and see what became of the map’s many ponds, mires and rivulets.

Digging into the details

First of the squares

At this period, most of the area’s famous squares were not even a twinkle in the developer’s eye. We find some exceptions, though, to the south of the map. Lincoln’s Inn Fields is the most prominent. This abode of lawyers has always been open land, but was enclosed by posh houses by the mid-17th century. Nearby Red Lyon (now Lion) Square is much smaller and slightly later. It was laid-out in 1684 by the notorious housebuilder Nicholas If-Jesus-Christ-had-not-died-for-thee-thou-hadst-been-damned Barbon. (Yes, his real name.)

The first ‘proper’ Bloomsbury square was, indeed, Bloomsbury Square. This appeared in the 1660s just as Charles II was getting used to his crown. None of the original buildings survive, but the later rebuilds still look magnificent. The north of the Square is dominated by Bedford House, town house of the Dukes of Bedford, the area’s main landowner. It’s sobering to think that the extreme squalor of the St Giles rookery was just a two-minute stroll from this monster mansion. The only other square on this panel is Queen Square, which was completed in 1725. Many more would soon follow as the open fields got developed.

The British Museum in waiting

Next to Bedford House we see the similarly sized Montagu House, built with consummate predictability for the Duke of Montagu. More interestingly, this is the building that would, just 13 years after our map, become the nucleus of the British Museum. That institution would gradually grow to cover the entire footprint of Montagu House — almost exactly, in fact. The semi-circle we see to the north of the grounds lines up neatly with today’s rear entrance to the museum.

Foundling Hospital

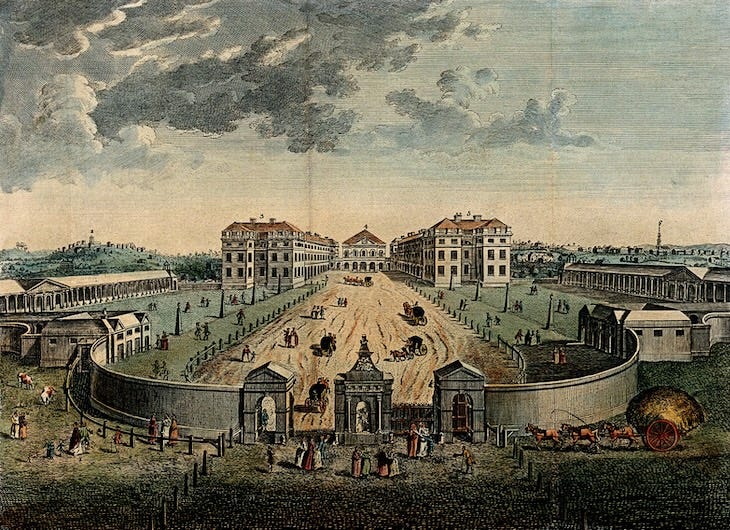

The built-up area cuts off abruptly north of the great houses and Queen Square. From here, future-Bloomsbury is still fields. One major exception is the Foundling Hospital in the upper-centre of the map. This institution was created in 1739 to look after children whose own parents were unable to do so. It was a new-build at the time of our map. Indeed, some of the blocks are still under construction, as indicated by the structures to the east that lack cross-hatching on the map.

By 1753, the blocks were complete, and the perimeter wall had been extended southwards as shown in the illustration above. Parts of the side wings, shown in the illustration but not yet built on the map, survive today, and border a children’s playground. The main blocks are long gone, but the charity lives on through the wonderful Foundling Museum on the same site.

Burying grounds

Just north of the Foundling estate, we can see twin cemeteries marked as Bloomsbury Burying Ground and George ye Martyr’s Burying Ground. Remarkably, these survive today in recognisable form. The dividing wall has long gone, but a handful of stones still show its course. This land was used as burial ground for the two hemmed-in churches of St George’s Bloomsbury (the Hawksmoor church near the British Museum) and St George-the-Martyr in Queen Square. Seek this space out if you’ve never done so. It’s one of those quiet, little-known wildlife havens tucked away from the busy streets.

Black Mary’s Hole

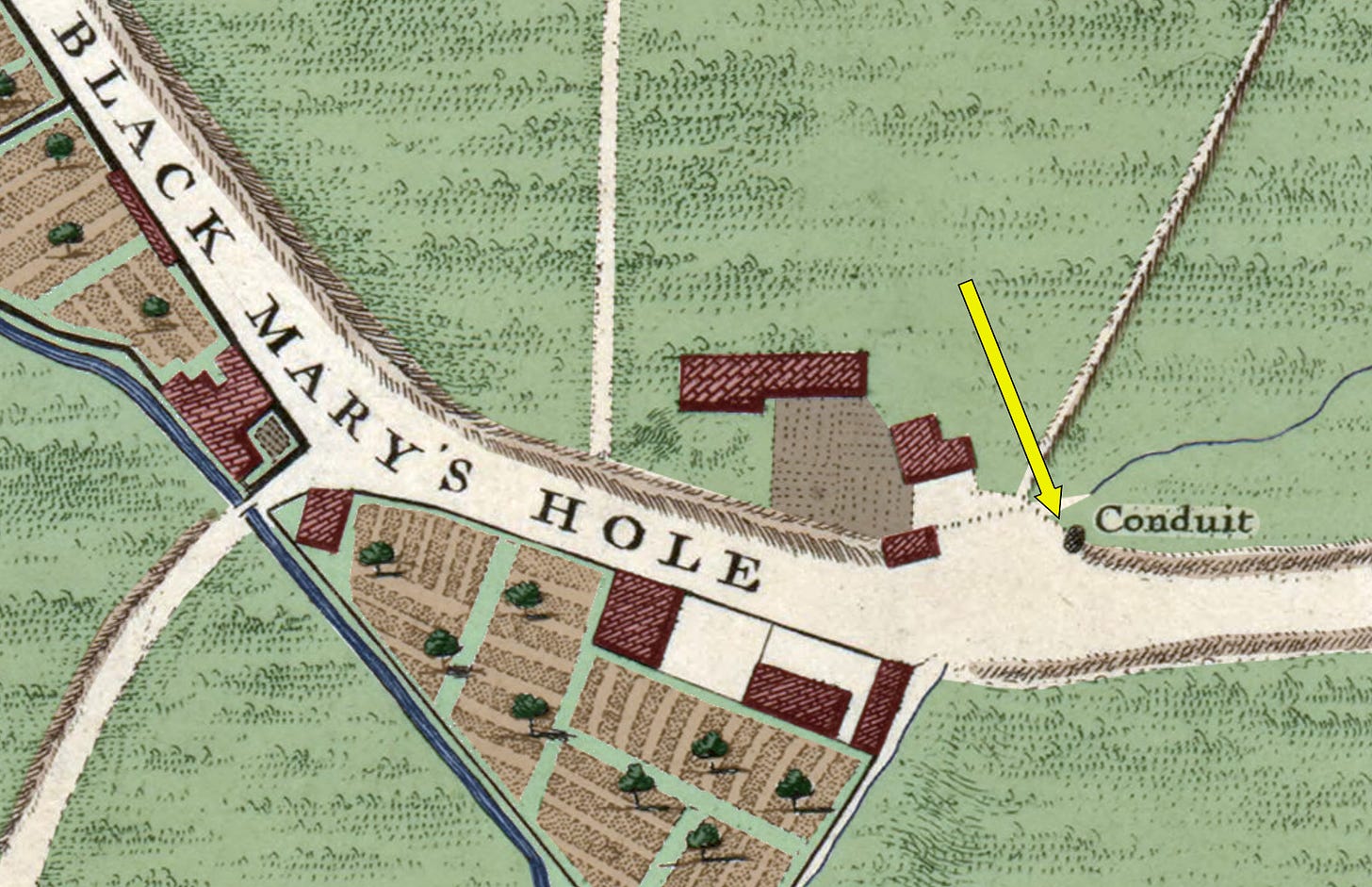

The most enigmatic place name on the map, up in the top-right, has long puzzled historians. Any number of identities for “Black Mary” have been suggested, from nuns to cows. In recent years, opinion, evidence and grassroots energy have coalesced around the name Mary Woolaston, who is described in a 1761 source as “a blackmoor woman… who about 30 years ago lived by the side of the road, near the stile in a small circular hut built with stones”. Her ‘Hole’ is doubtless one of the many springs or wells along the course of the River Fleet. Pure speculation here, but could the rounded feature on the map labelled ‘conduit’ have developed from her “circular hut built with stones”? It’s right next to a field where we might expect to find a stile.

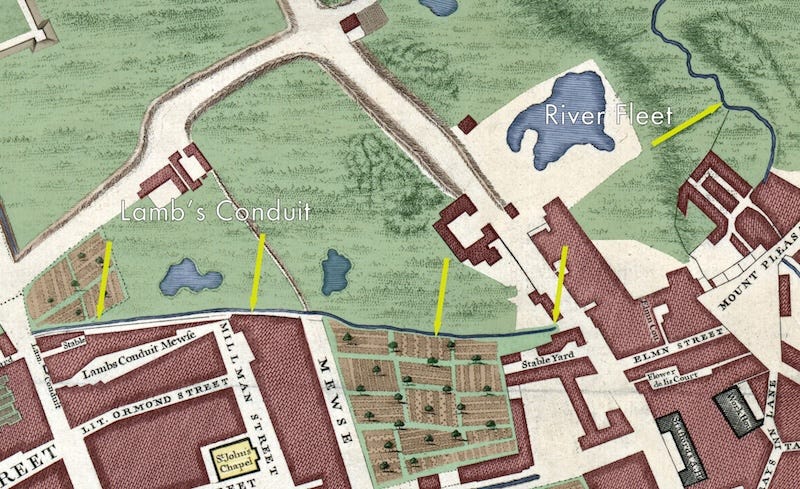

Lambs Conduit Fields

Much of the grassy area to the west of the map falls under this label. The name is not a reference to ovine livestock, but to a Mr William Lambe. In Tudor times, this gentleman granted a hefty sum of money to repair and improve a conduit that carried fresh-ish water from the River Fleet into the Bloomsbury area. We can see it on the map:

The conduit, of course, gives its name to Lamb’s Conduit Street and the Lamb pub. A marker stone referencing the conduit head can still be found down Long Yard, to the east of Lamb’s Conduit Street.

Tracks and roads

Numerous routes wend their way through Lambs Conduit Fields. Some of these are easily identifiable. The “Road to Hampstead and Highgate” is what we now call Gray’s Inn Road. Meanwhile, the wide roadway labelled as Black Mary’s Hole corresponds to King’s Cross Road.

Elsewhere, almost every track and path we see has been obliterated. Bloomsbury was developed on a loose grid system, which paid little heed to the existing footpaths or field boundaries. Most of the land had one owner: the Duke of Bedford. He was troubled with very few restrictions when it came to developing the land. Hence, the modern street plan rarely matches up with any 1746 trackways, other than the two cases mentioned above (there is another, which I’ll broach on Friday).

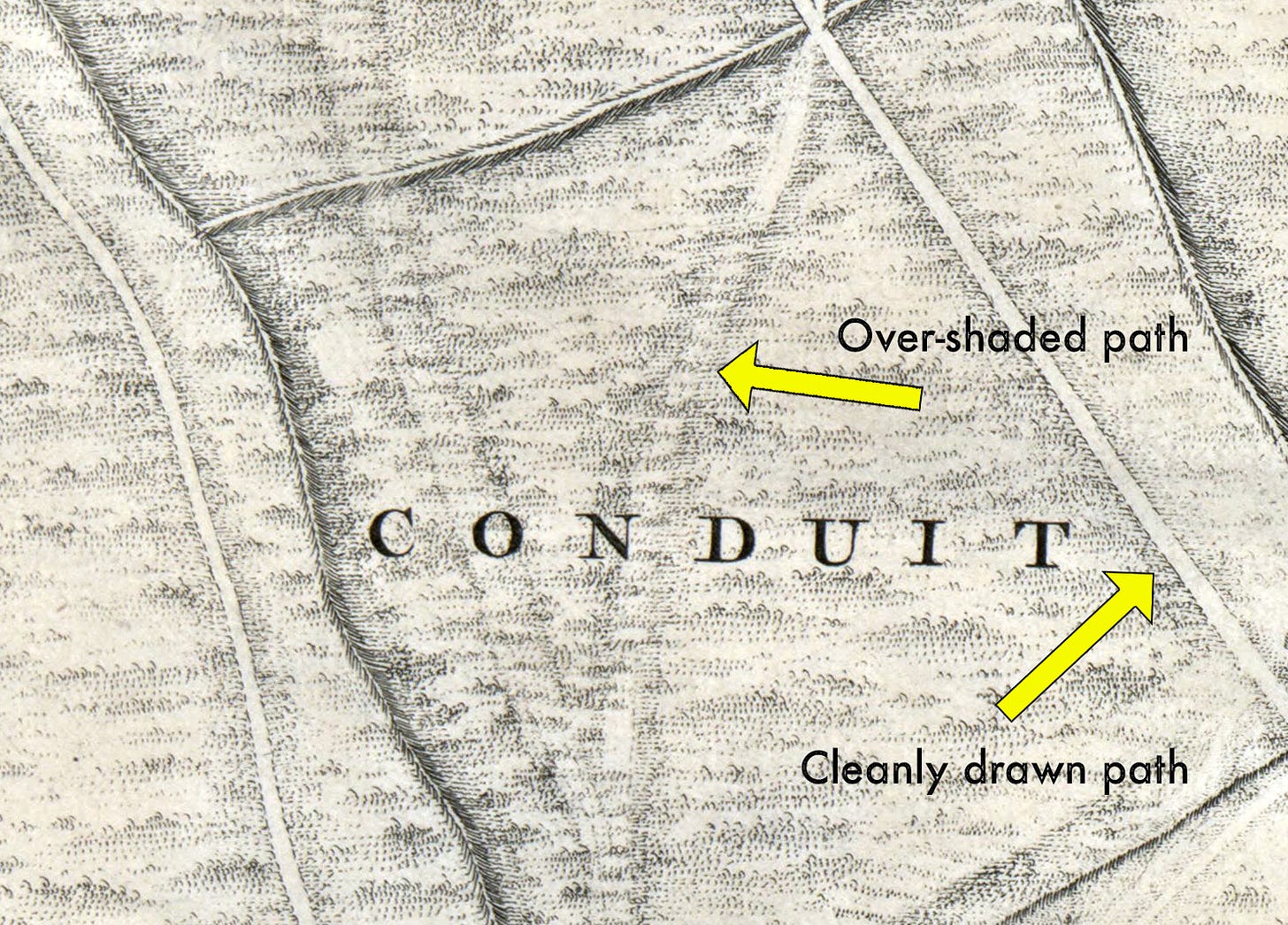

Here’s one curious feature I noticed while colouring in the map. In some places, the cartographer seems to have sketched in a trail across a field, only to then shade over it.

I’m not entirely sure why. Three theories:

1. Some kind of error, which the illustrator then tried to cover over. I doubt this, because the map is so carefully constructed elsewhere.

2. Old paths that have fallen out of use, but which are still visible beneath the weeds.

3. “Desire lines” — unofficial paths that people create naturally, as the shortest route from A to B. We still see these in parks or across wasteland today. The over-shaded paths in the map do seem to connect up points of interest, so this is the explanation I want to believe in. But it is only speculation.

A few notes on the built-up area

I’ve ignored the lower part of the map because, frankly, the open fields are more intriguing. But we do find a few points of interest down below. One of the most striking surprises, for me, was discovering the large basin in the middle of Lincoln’s Inn Fields. I had no idea such a water feature ever existed. It’s huge and would have been one of the largest bodies of water in central London (not counting the Thames or Royal Park lakes). I can find very little online about this basin, only that is was short-lived, unpopular and filled in around 1790.

Gray’s Inn, another legal enclave north of Lincoln’s Inn, has a very similar footprint today to that shown in the 1746 map. It even retains some of the tree-lined avenues, though heavily remodelled. I was pleased to see that the map shows a declivity from “The Kings Way” (now Theobald’s Road) down to the gardens. That gradient is still very noticeable today. It’s also interesting to note that the land immediately north of Kings Way, including the future home of Dickens on Doughty Street, remain as cultivated land in 1746, while houses have sprung up to the east and west.

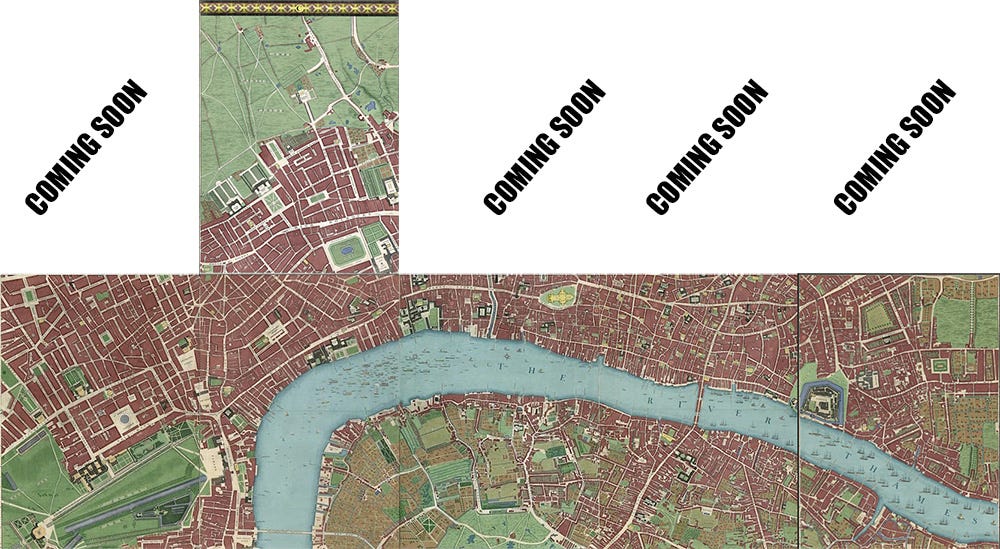

Finally, as is now traditional, I’ve bolted together the six panels I’ve coloured in so far, to get a better sense of how the project is shaping up.

I hope, one day, to get the map printed out and exhibited somewhere, once all 24 panels are coloured in. We’re now a quarter of the way!

I shall leave things there for now, but I would welcome any further thoughts or observations in the comments. And feel free to email me any time on matt@londonist.com Thanks for reading!

Absolutely beautiful! Love all the commentary too. The Duke of Bedford’s path going north from Southampton Row crossed the Euston Road (not yet built in Rocque’s time) and onto his holding of fields next to Hampstead Road just south of the Mornington Crescent area

Fascinating as always. I hope the finished work does get exhibited, your efforts surely merit it. This area is of particular interest to me, as I went to the LSE just south of Lincoln's Inn Fields & had a tumour removed in the National Neurological Hospital on Queen's Square forty years later.