“London is in the throes of an epidemic which is daily claiming victims, north, south, east, and west, and is already becoming known as the new kind of yellow fever.”

So ran an item in the Leominster News, 10 August 1906. The problem was banana skins. London was becarpeted in yellow slip-hazards. People were getting hurt. I’ve even found accounts of death by banana skin.

Today, we might scoff at the idea of slipping on banana peel. It is the stuff of slapstick, largely confined to low-brow TV. But to Edwardian Londoners, this was a very real danger. Indeed, I was amazed to discover just how many Londoners were injured or killed by the exotic offcasts. In today’s Londonist: Time Machine, I’d like to get beneath the skin of this forgotten aspect of social history. First, the banana back-story…

London’s first banana “hurteth the stomach”

The first person to sell bananas in London is well documented. Herbalist Thomas Johnson displayed a bunch in his Holborn shop as early as April 1633. The curious specimens, shipped over from Bermuda, were probably closer to plantains than what we might regard as bananas. Johnson, who revised an important volume on botany, provides a lengthy description of their appearance, taste and medicinal use. He didn’t exactly gush with praise:

"…the fruit hereof yieldeth but little nourishment; it is good for the heat of the breast, lungs, and bladder; it stoppeth the liver, and hurteth the stomach if too much of it be eaten, and procureth looseness in the belly.”

It’s safe to say that bananas did not immediately take the capital by storm. The fruit1 spent the next two centuries as a rich-person’s novelty. Few Londoners would have ever seen a banana, let alone tried one.

Joseph Paxton ‘invents’ the modern banana

The origins of the modern banana begin with a name that will be familiar to many readers: Joseph Paxton. The architect of the Crystal Palace cut his teeth in the gardens of Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, where he built a succession of glass houses for exotic plants.

In 1830, he obtained a banana plant from Mauritius and successfully installed it at Chatsworth. It produced bananas from 1835. These were mostly kept in-house, for the delight of the Duke of Devonshire and his guests. Eventually, specimens of the variety were sent overseas for cultivation in the topics. The so-called ‘Cavendish’ banana — after the Duke’s family name — proved very robust and came to dominate the market. Today, almost every banana consumed in the western world is a descendant of Paxton’s curlers.

The banana goes mainstream

It took a while for the industry to get going. The first low-cost imports came to London from the Canaries in the 1890s. The goods were not always of the highest quality. We read of costermonger Henry Nathan who, in 1897, was arrested for selling black bananas (“disgusting things… perfectly rotten”) in Chrisp Street Market, Poplar. Another vendor was fingered for dispensing shrivelled bananas in Battersea as early as 1895.

The fruit, good or bad, remained an infrequent sight on London’s barrows. In 1902, a newspaper item noted that hardly any fruiterers stocked bananas, though the occasional costermonger could be found. Shortly thereafter, the market unzipped. Between 1901 and 1904, England’s imports went from 1.5 million bunches per year to 5 million, mostly from the Canaries and Costa Rica. The game-changer would come the following year after Jamaica, newly recovered from a crop-destroying hurricane, joined the import market.

A glut of bananas

Avonmouth, Bristol became the chief landing place for bananas. In just one week in April 1905, it received 78,000 bananas from Jamaica and Costa Rica. The biggest importer was Elders & Fyffes — still a well-known importer today, with its blue “Fyffes” stickers. The company ran a fleet of steamers across the Atlantic, each equipped with refrigeration machines to keep the fruits fresh.

From Bristol, the bananas were rapidly conveyed by rail to London Paddington. A typical load would see 12,000 bunches reach the capital in one cargo. From here, 120 vans despatched the bananas to Borough, Spitalfields and Covent Garden markets.

Those early importers were perhaps a little too keen. Central market traders reported a glut that could not be shifted at any price. The solution was to sell the bananas by the ton to hawkers, who would then take them by wagon out to rural areas. “They find the villager and labourer most partial to cheap Jamaican bananas,” says one report. The typical going rate was two bananas for a penny.

1905 also saw the first ‘claret bananas’ reach our shores. Yes, red bananas are a thing, and Londoners got to taste them more than 100 years ago. The strange fruit from Barbados never caught on, despite supposedly having a “much finer flavour” than yellow bananas.

“Insidious yellow pavement traps”

By 1906, the yellow fruit had been thoroughly democratised. Indeed, Londoners were getting hooked on the things. Thousands of bananas were consumed daily. They were the perfect on-the-go food. Nutritious, cheap and self-packaged, the banana was a practical foodstuff for the busy worker. Just one problem, though. Edwardian London did not have many bins. The inedible peel was usually thrown onto the floor. While it awaited the attention of the street sleeper, the peel became a hazard to pedestrians and horses.

“There is no escape from the banana pest for rich or poor,” agonised the Leominster News that year. “…there is hardly a family which has not a member who at some time has not suffered from the ‘banana fall’.“ Slips by this time were so common that ‘banana fall’ became a widely recognised colloquialism.

“London from end to end is strewn with banana skins,” it continued. “A banana skin, any part of it, is the most effective and expeditious means of breaking an arm or bruising a head which nature has yet devised.”

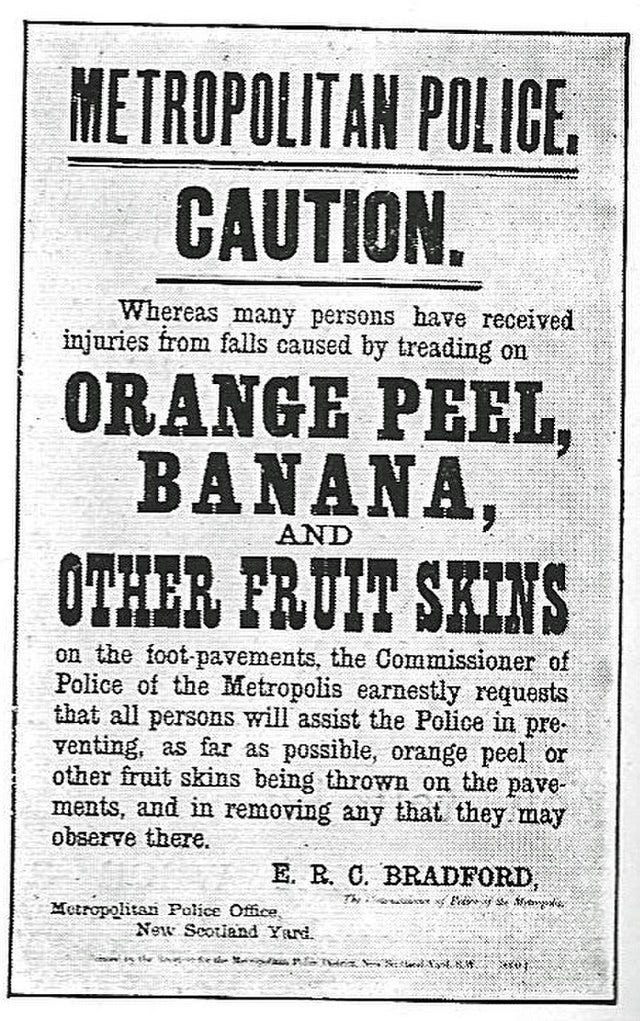

The problem was not entirely new. As early as the 1890s, we find press reports of banana skins causing a nuisance along Kilburn High Road. The Metropolitan Police had even printed notices to dissuade people from littering with orange or banana peel:

The measures clearly had little effect. In 1902, the South London Observer printed some sobering statistics, which I print in full:

Just to repeat, and with emboldened words to convey my incredulity: fourteen people slipped on banana skins on Fleet Street and the Strand alone, and were injured enough to need treatment… in just one day. That’s staggering, in more ways than one.

The uptick in imports from 1905 greatly exacerbated the problem. The police (famously nicknamed ‘the Peelers’, though for other reasons) needed to take action against the litterers. One such culprit was Henry George Murray, an elderly man found tossing banana skins in Moorfields in July 1906. He argued back that there was nowhere to dispose of the skin, and that he couldn’t be expected to carry it in his pocket all day. The unsympathetic judge, a former Lord Mayor, fined him 2s 6d.

A few days later, London County Council brought in a bye-law specifically aimed at punishing peel tossers: “No person shall deposit in any street or public place to the danger of any passenger the rind of any orange, banana, or other fruit.” A maximum penalty of 40 shillings could be imposed.

The first case under the new bye-law, against a young girl called Rose Day, took place in December 1906. Day was told she had behaved in a “very foolish manner” in wilfully dropping a banana skin, but was let off without fine.

Were the authorities over-reacting? Not a bit of it. Several cases of injury from the “insidious yellow pavement traps” are immortalised in the newspaper archives. An elderly lady broke her leg after unwittingly doing the banana splits in Chelsea in May 1906. “The danger is real and urgent,” wrote one London correspondent, “and the authorities are at a loss to find a remedy.”

The problem was so great that it began to show up in insurance records. “Many of the claims made on companies under the [1906] Workmen's Compensation Act have arisen from servants slipping on the terrors of the public path,” revealed one newspaper in 1907.

Death by banana

Those with broken arms or legs were the lucky ones. All too many people would lose their lives to the xanthous menace.

The earliest example I’ve found in London involved Mrs Ruth Martha Nash of Camberwell. In August 1904, she slipped on a banana skin outside the Red Lion, Walworth Road, fracturing her leg. She would later die of complications. An earlier case, in January 1904, saw Myra Fletcher fall to her death in Chapel Street, Islington after skidding on orange peel — often cited as of equivalent danger to the banana.

This was not an isolated case. In January 1905, a heavily pregnant lady named Mrs Rodwell slipped on banana peel on Wandsworth High Street, landing heavily. She later miscarried her child, probably as a result of the fall. Then in May 1906, 73-year-old Jane Wilkin was badly injured after sliding on a banana in Strutton Ground, Westminster. She too would later die from complications arising from the injury. A man in Bethnal Green joined this unfortunate group in September of that year. In 1907, a 72-year-old man called Patrick Heavican took a banana-induced tumble in Bath Street, St Luke’s. Badly bruised, he was helped back to his bed at the Holborn Union Workhouse but later died of “pneumonia, accelerated by the shock of the fall”.

Other cases can readily be found around the country. Architect James Sellers fatally smashed his head in Blackpool in December 1904. A slip in January 1906 killed grindstone merchant Alfred Rowley up in Newcastle. Around the same time, a lady in Dover lost her life from a banana-related fall. In 1911, it was the turn of a boot-maker in Aston.

That’s 10 fatalities in 11 years, all caused by slipping on a banana (or, in one case, orange) skin. There were undoubtedly others that didn’t make the press, or which I haven’t found. So while we may make light of banana slips, these cases show that the dangers are very real. People actually died from these things.

How did the crisis end? A bunch of reasons

As the years went on, the problem gradually faded. Bananas were scarce in the First World War, and all but absent in the Second. Meanwhile, improvements to public health, including better bin provision, attitudes to littering, and changes to consumption habits reduced the incidence of skins on the pavement. The old Gros Michel cultivar, common in Edwardian England, was switched to the potentially less slippy Cavendish variety — the one pioneered by Joseph Paxton. I suspect, too, that the rise of grippier, rubber-soled shoes has also reduced the risk.

Today, it is rare to hear of anyone slipping on a banana skin, let alone losing their life. The danger is still there, of course. The most recent incident I can find comes from 1991, when a crane operator on Horseferry Road is thought to have fallen to his death after slipping on a peel.

With litter once again on the rise thanks to a squeeze on council budgets, we should pay extra attention to where we step. The ‘banana fall’ is ripe for a return.

Now, having read about the dangerous fruit of the past, find out why the modern Londoner is slipping over on Limes, as told by one of Substack’s finest,

.

Thanks for reading! I’d love to hear your banana-themed anecdotes in the comments below. Or email me any time on matt@londonist.com.

Botanically a berry, apparently.

One of my clearest primary school memories is singing ‘let’s all go down the strand, have a banana’ in a school concert and being the one to hand a banana to the head teacher! Googling I can see I didn’t dream it & it was even covered by Blur who sadly seem to have removed the reference to bananas! Anyway I have always associated The Strand with bananas (& always felt it should be yellow on monopoly!)

Gros Michel bananas were largely cultivated in South America, as opposed to the European origins of the Cavendish. It disappeared through disease and bad weather conditions the Cavendish was immune to.